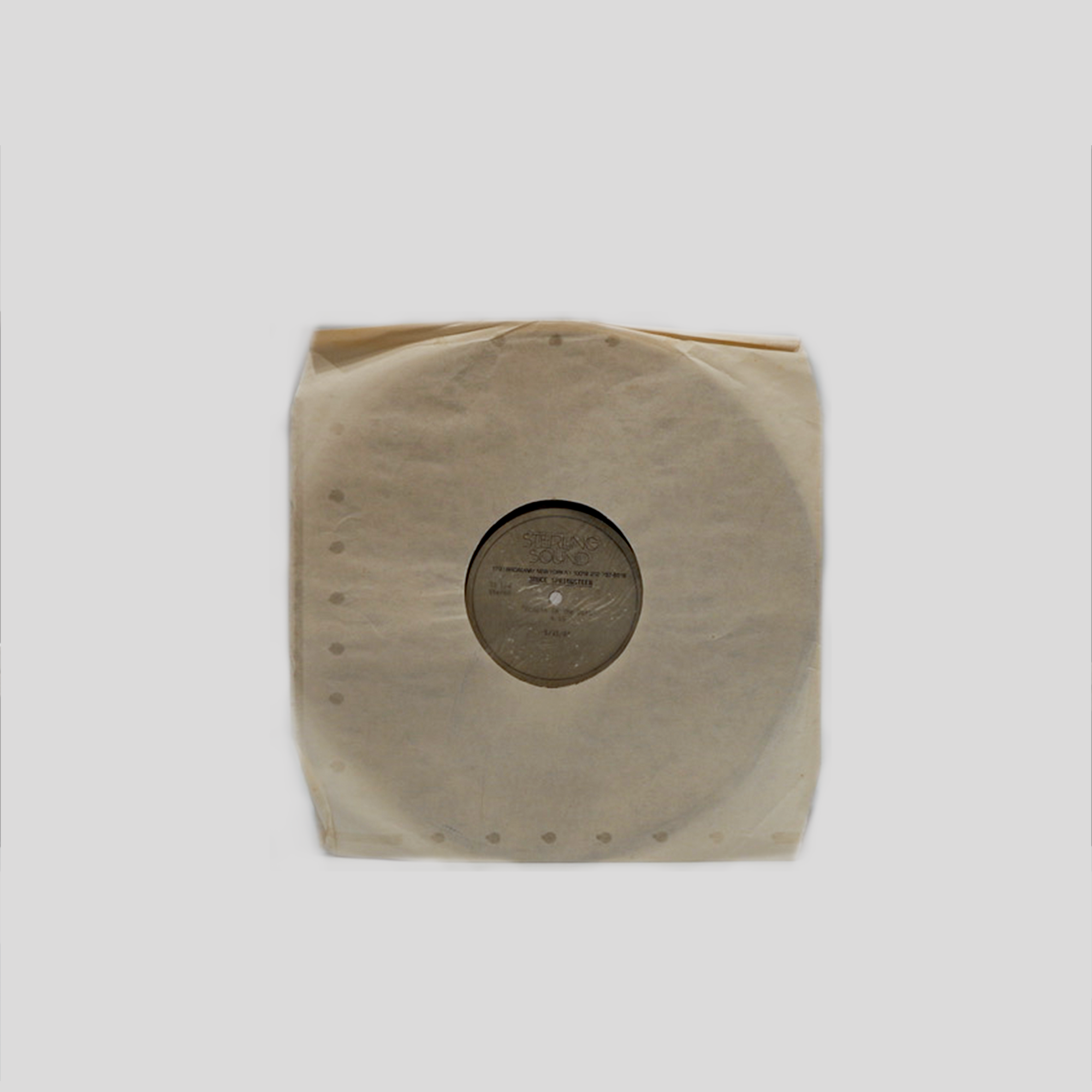

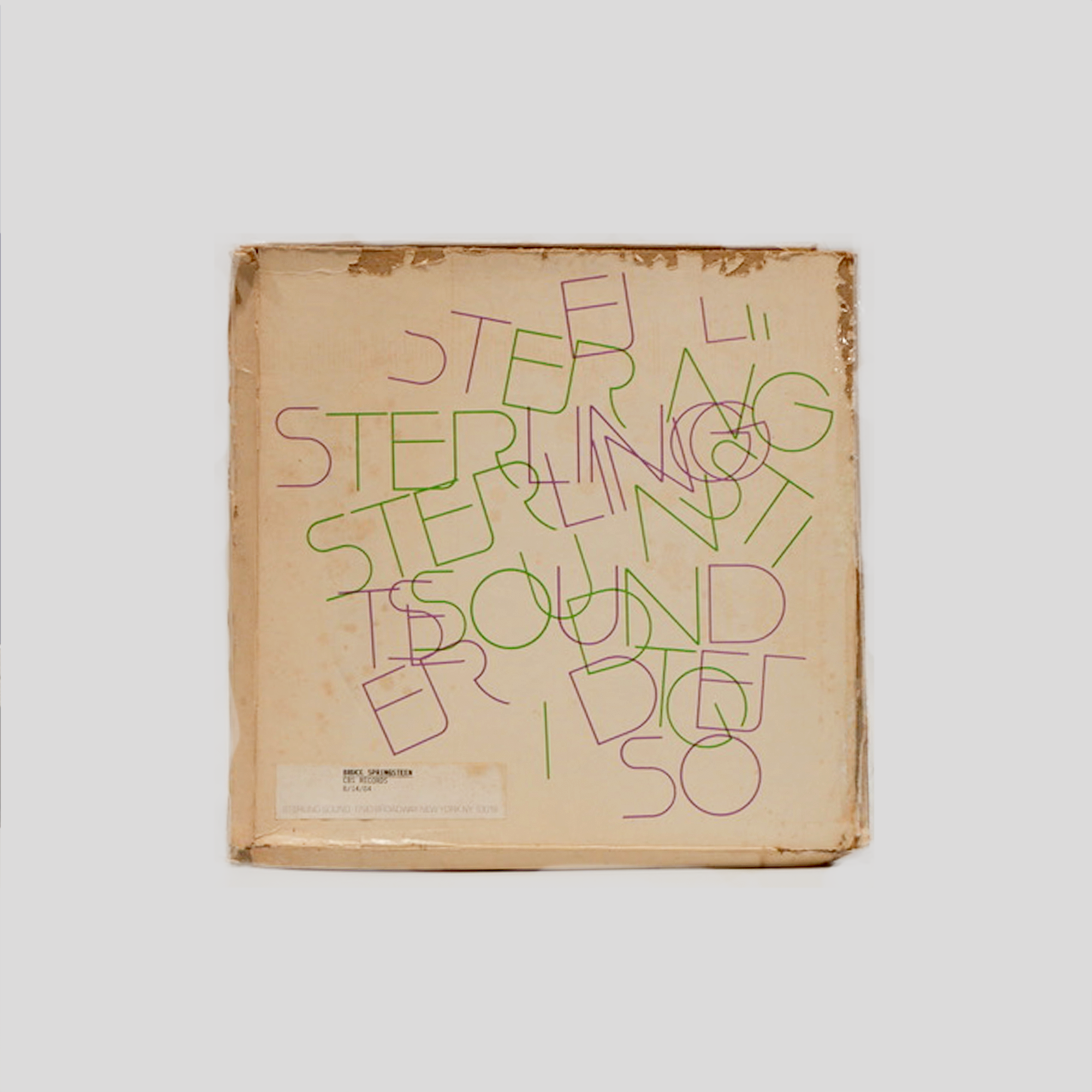

JAMES BROWN, DEF JAM, ROLLING STONES, BOB DYLAN, BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN, BEASTIE BOYS & MUCH MORE...

Arthur Baker is an architect of modern music—producer, DJ, record exec and true pioneer.

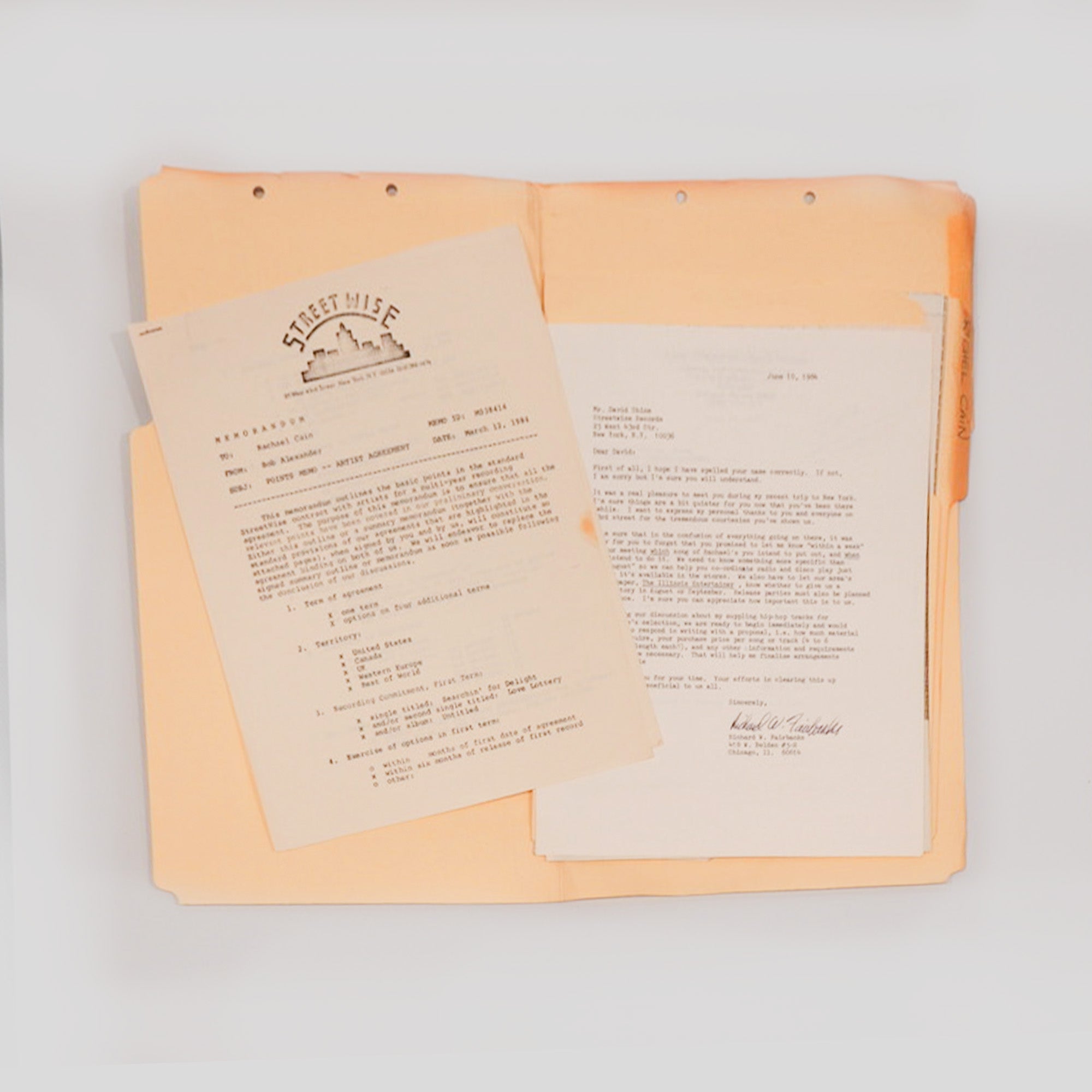

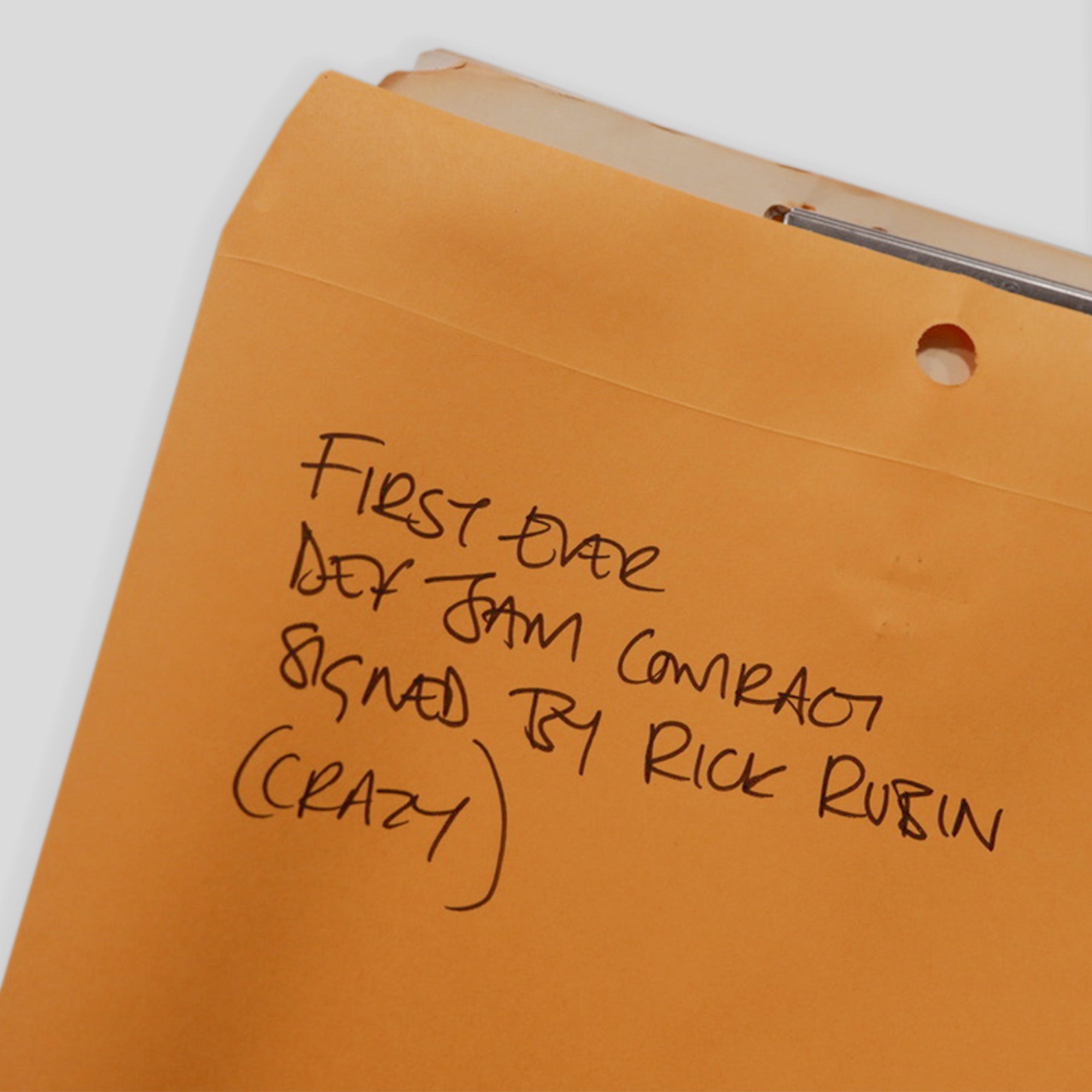

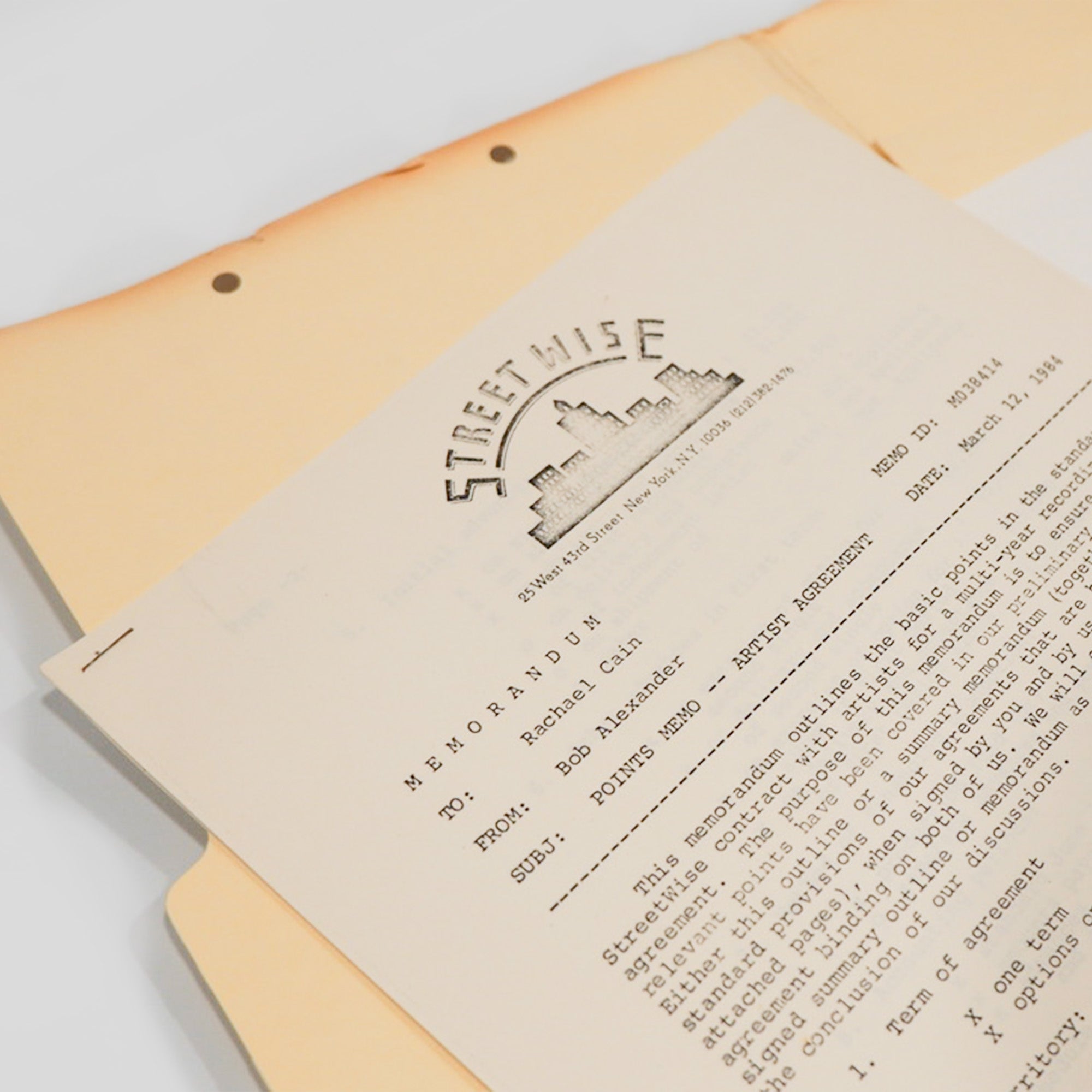

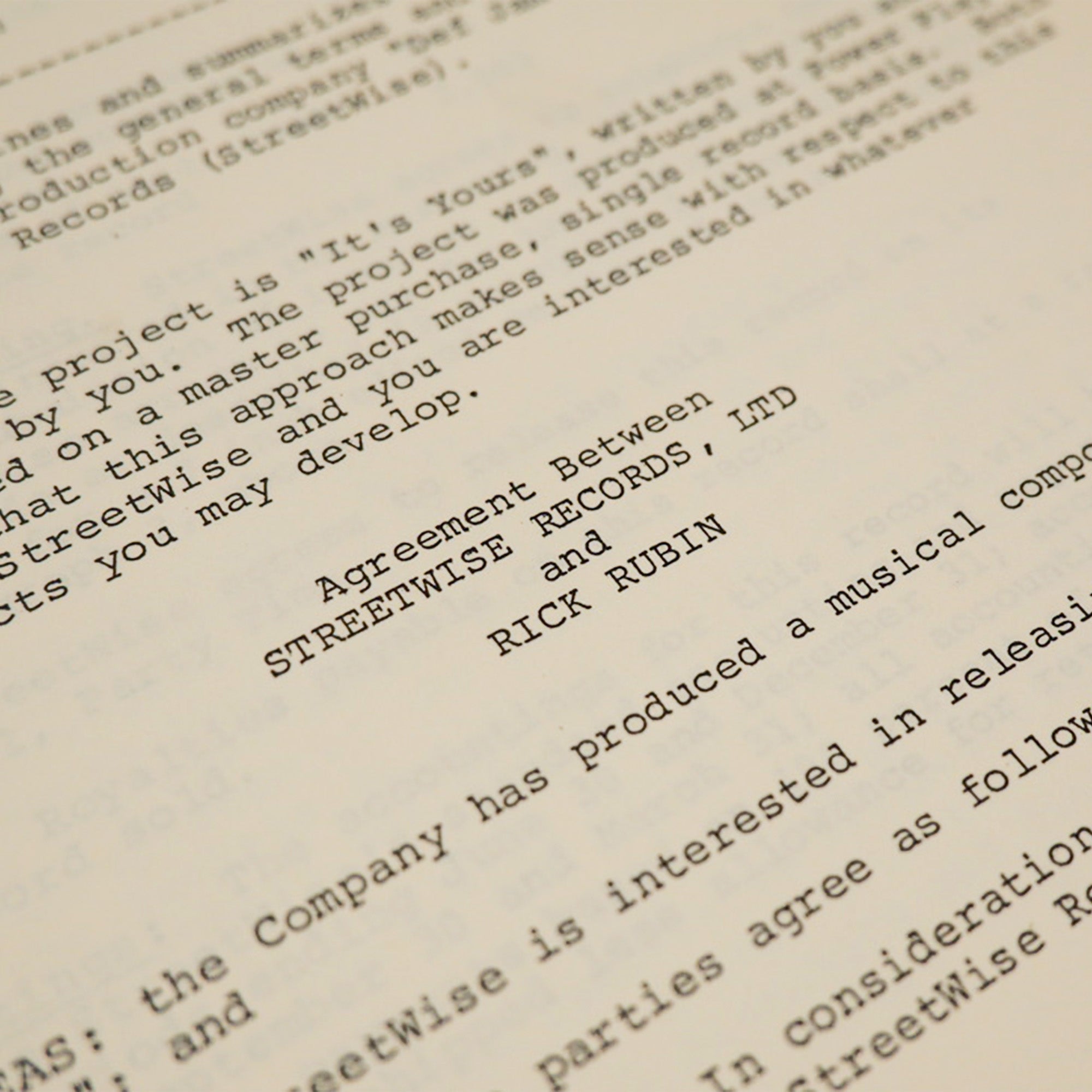

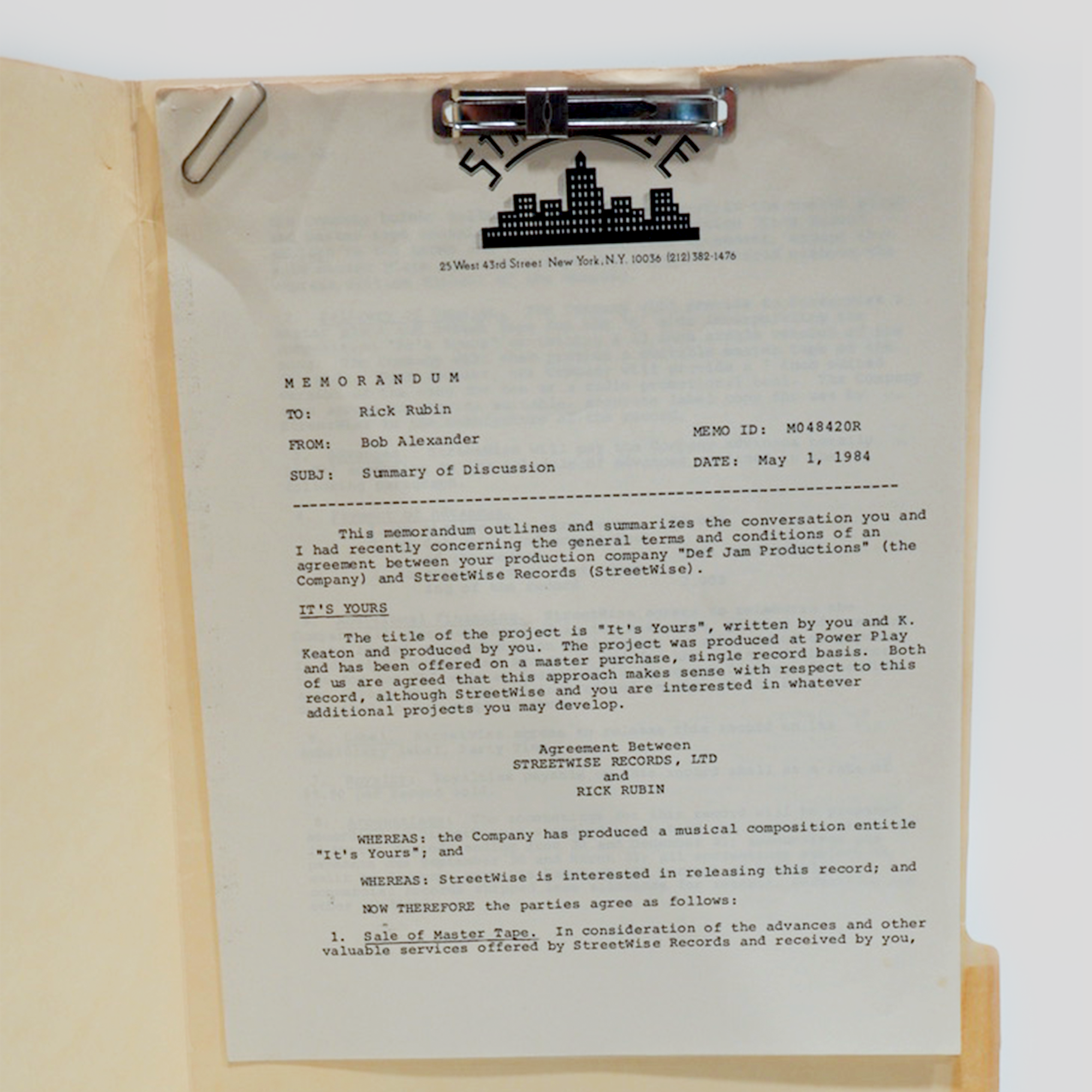

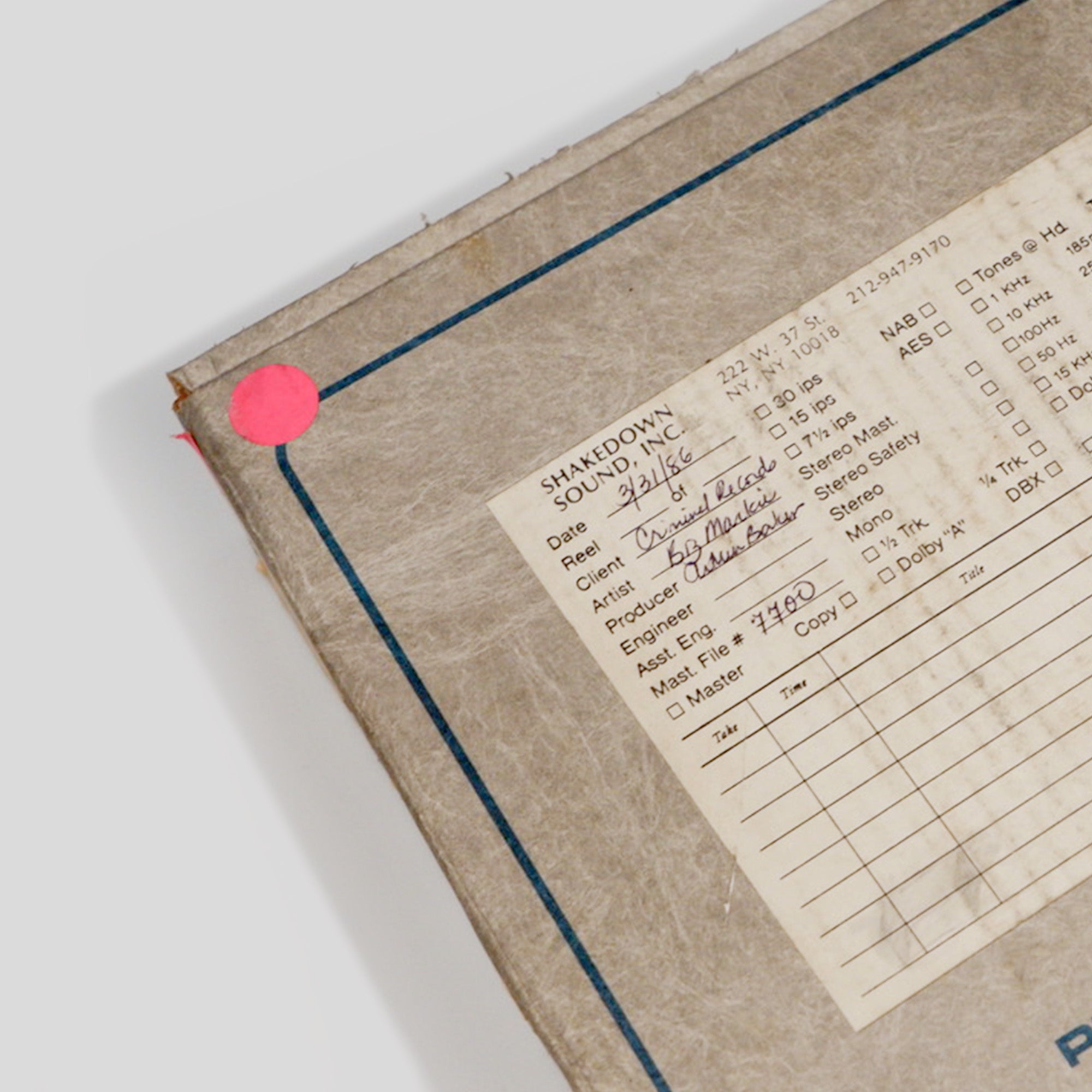

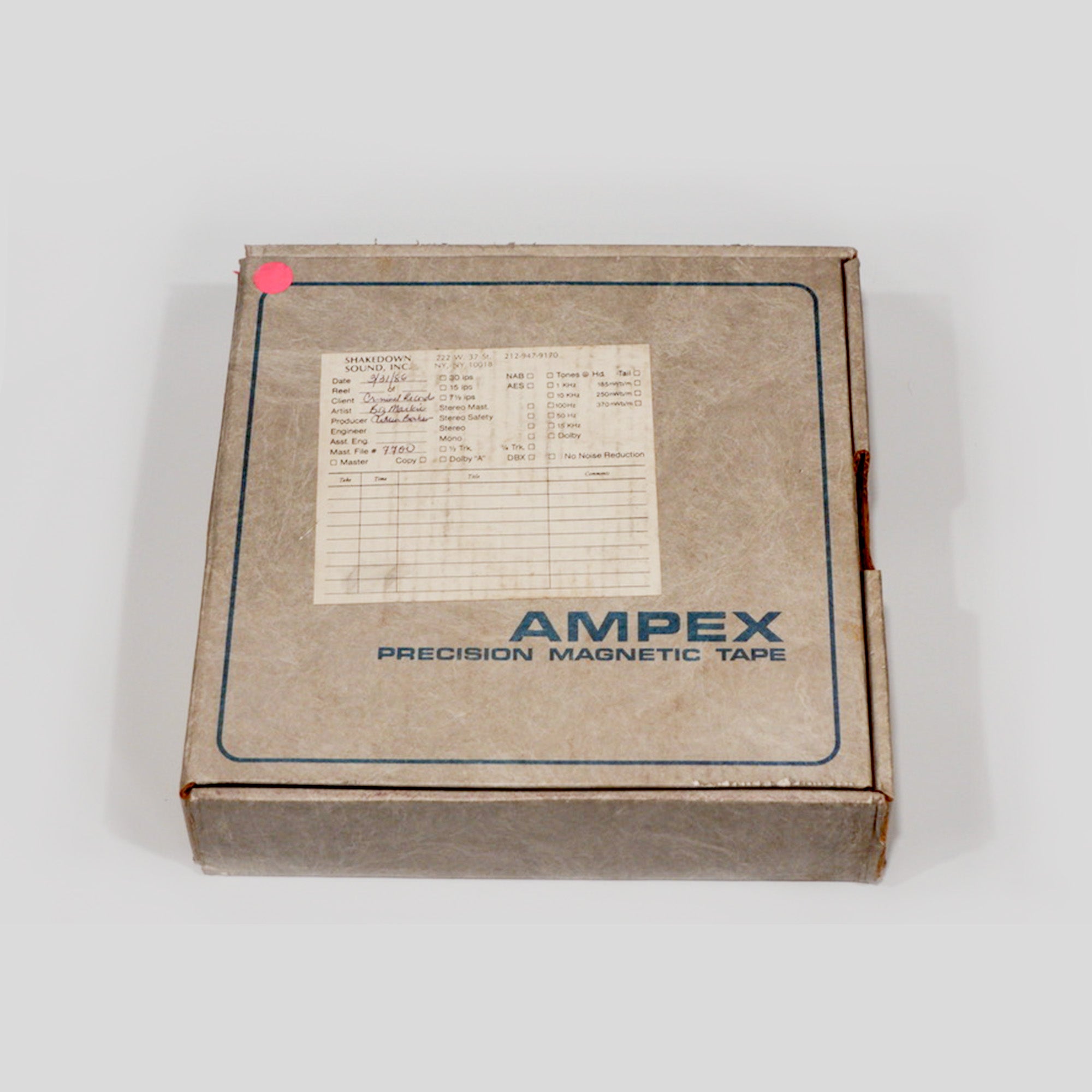

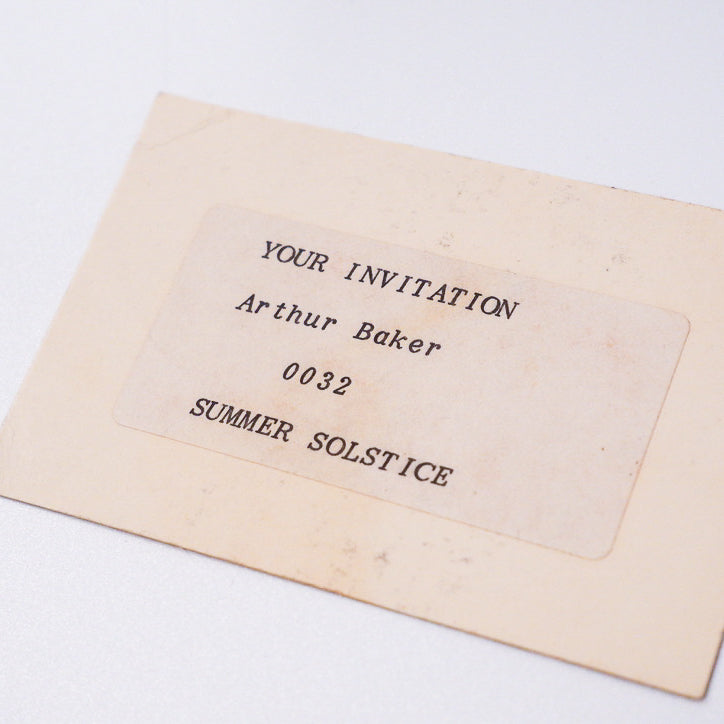

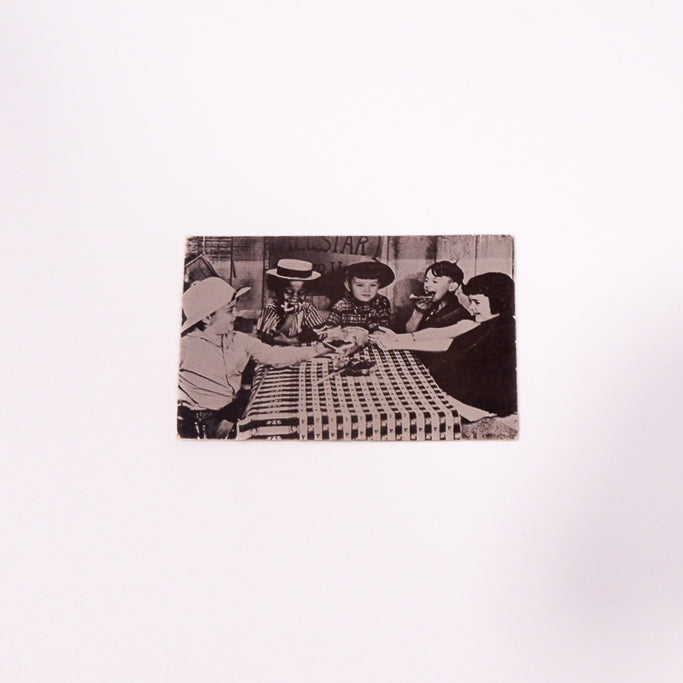

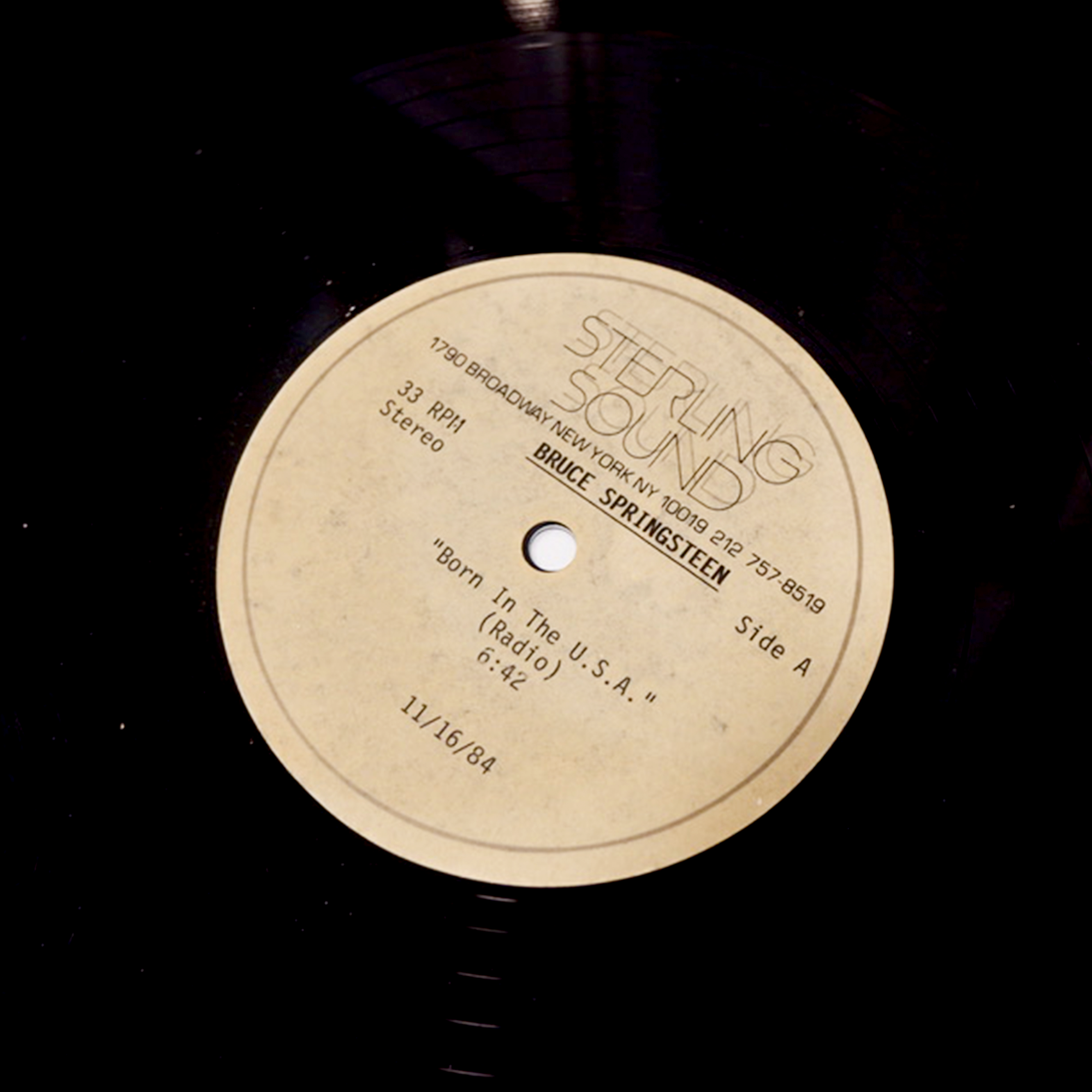

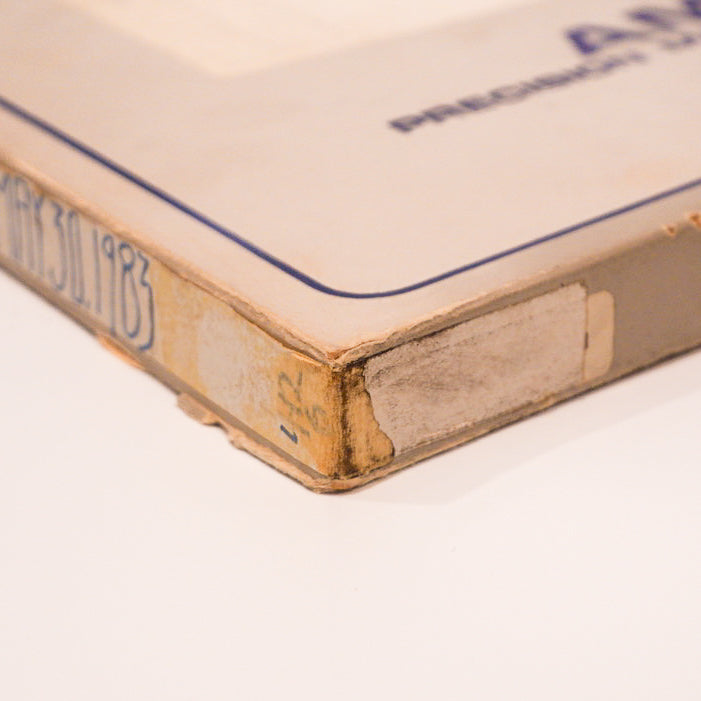

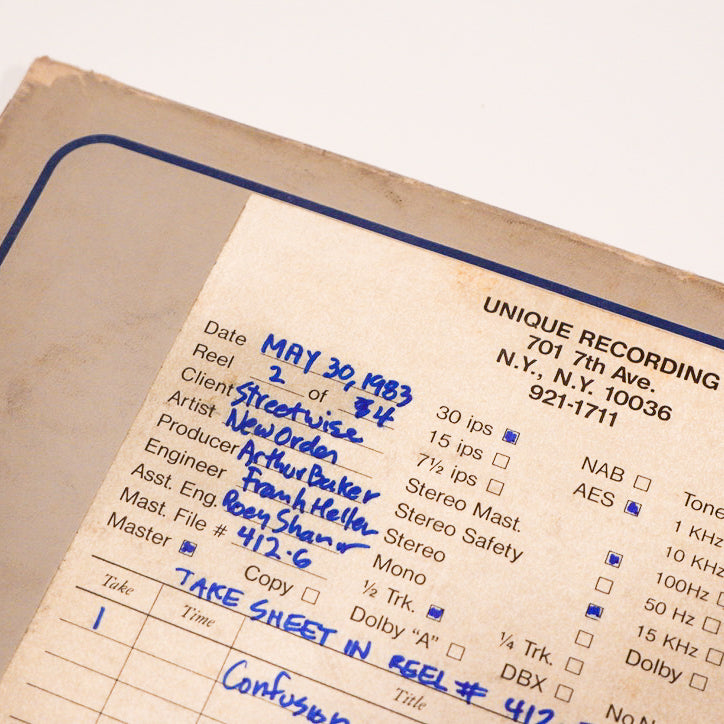

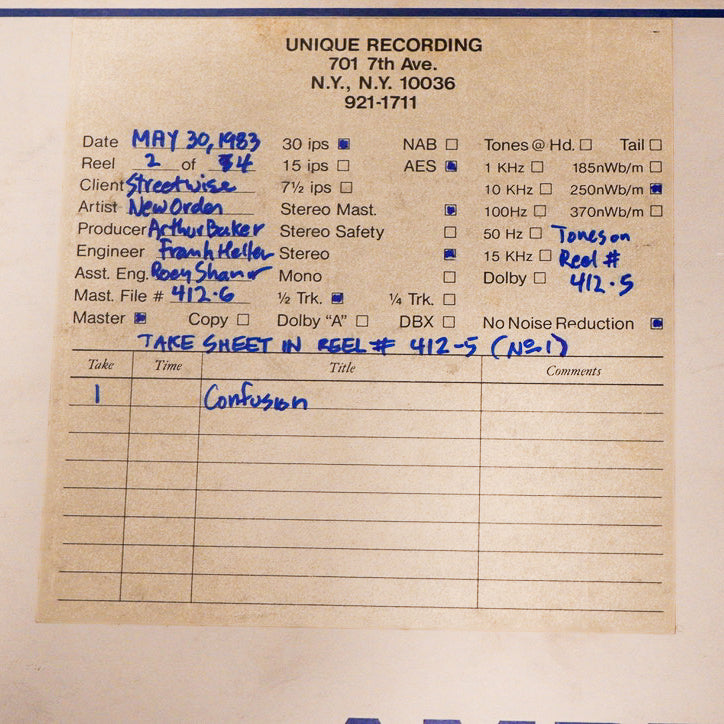

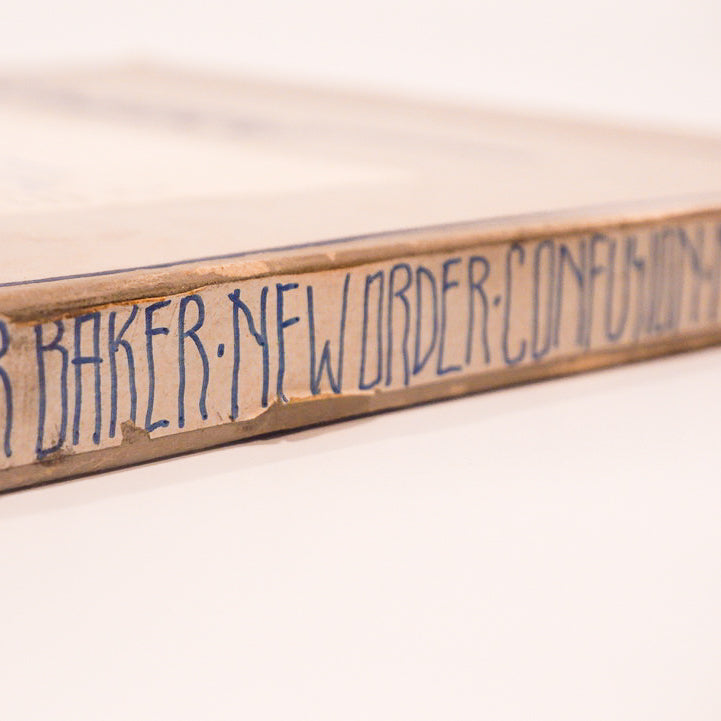

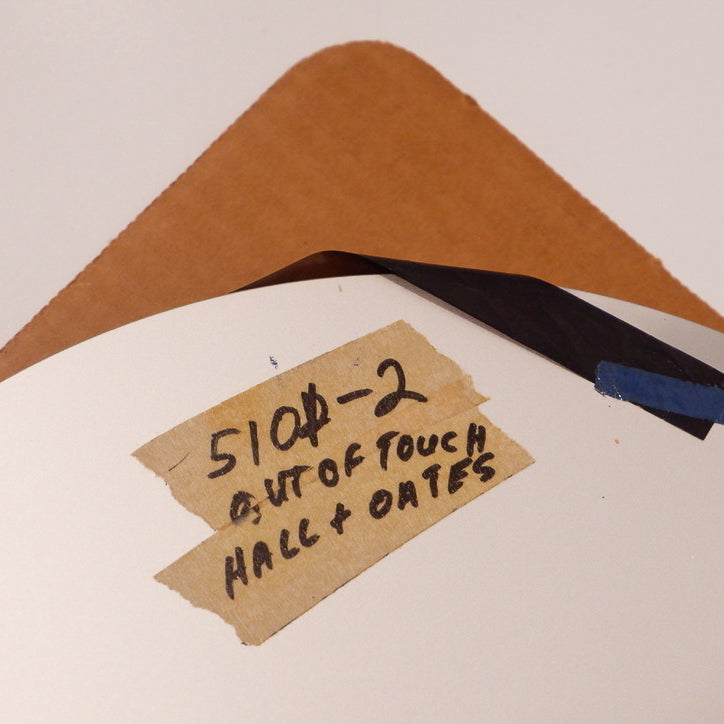

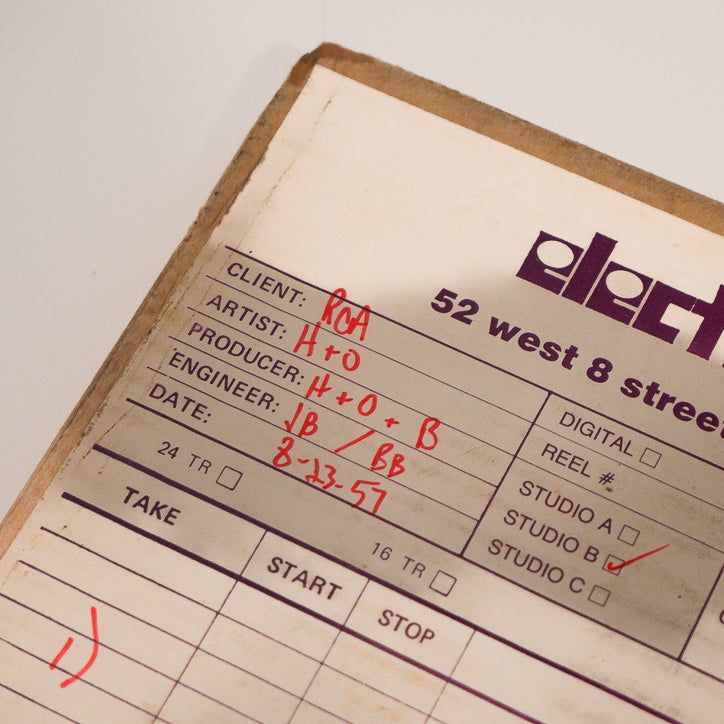

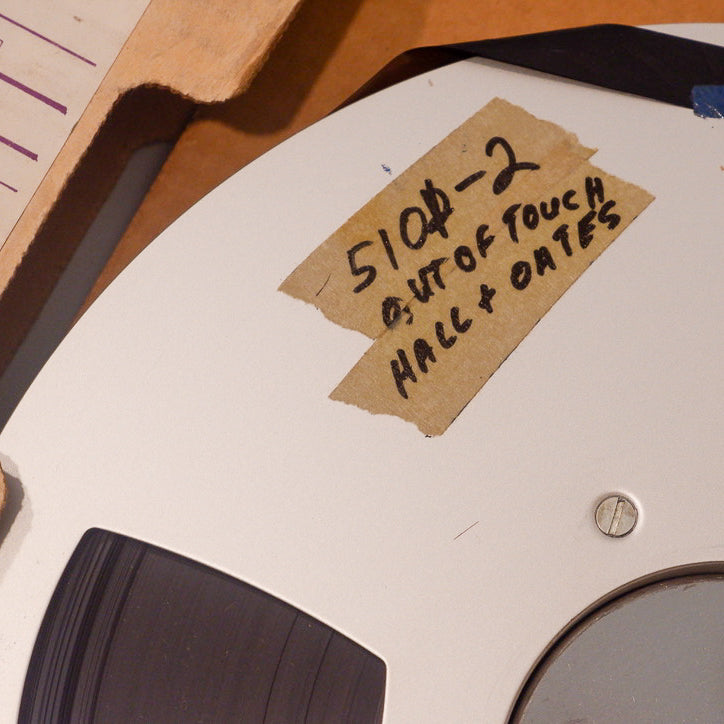

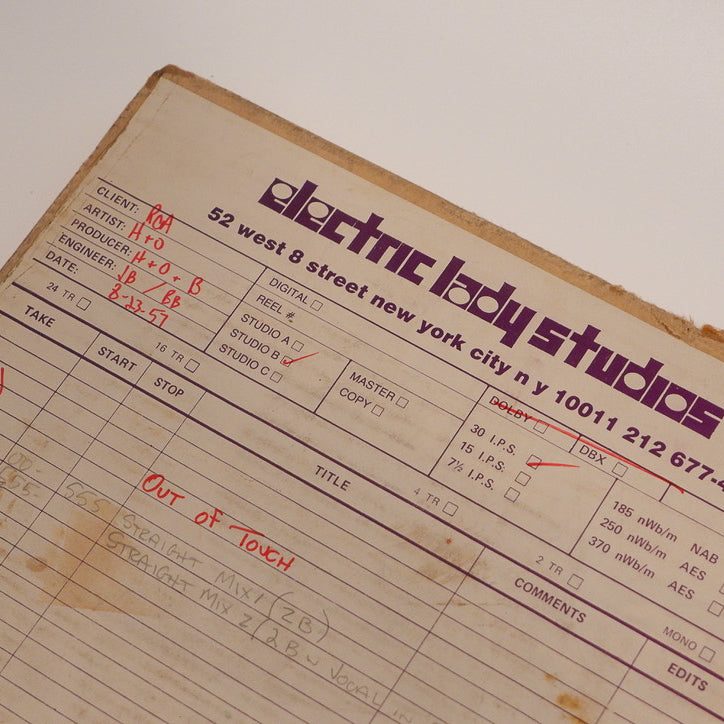

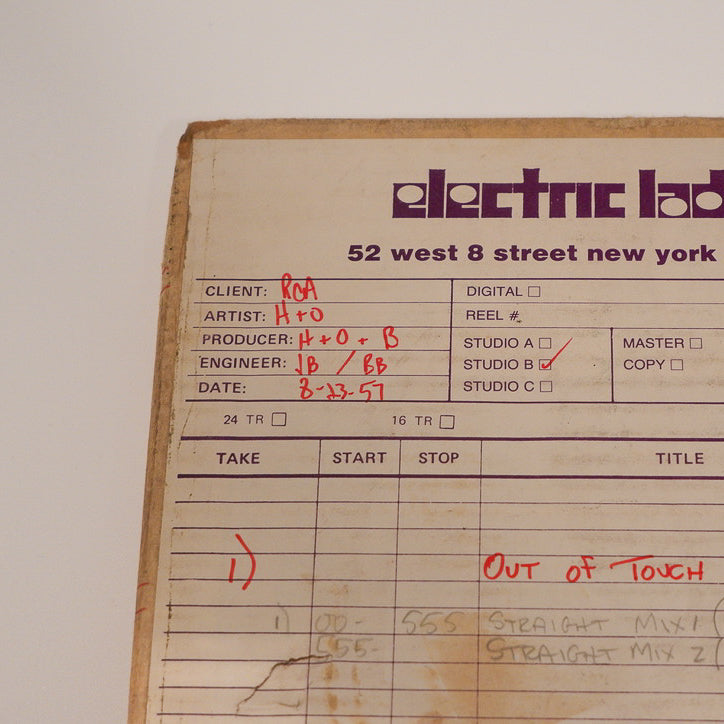

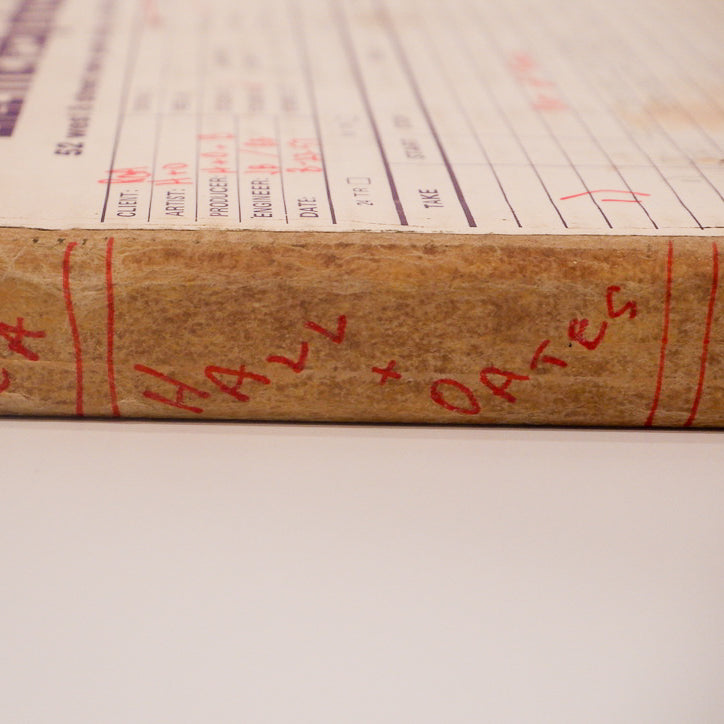

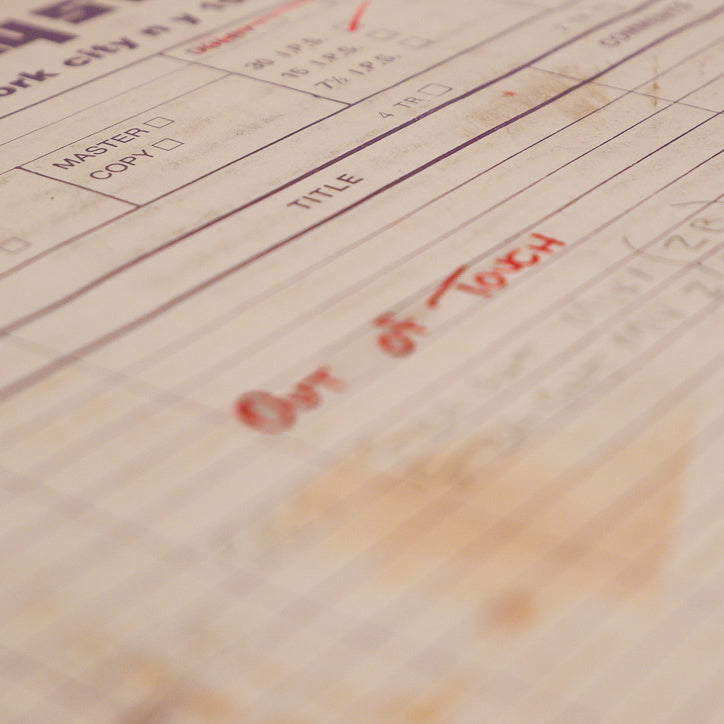

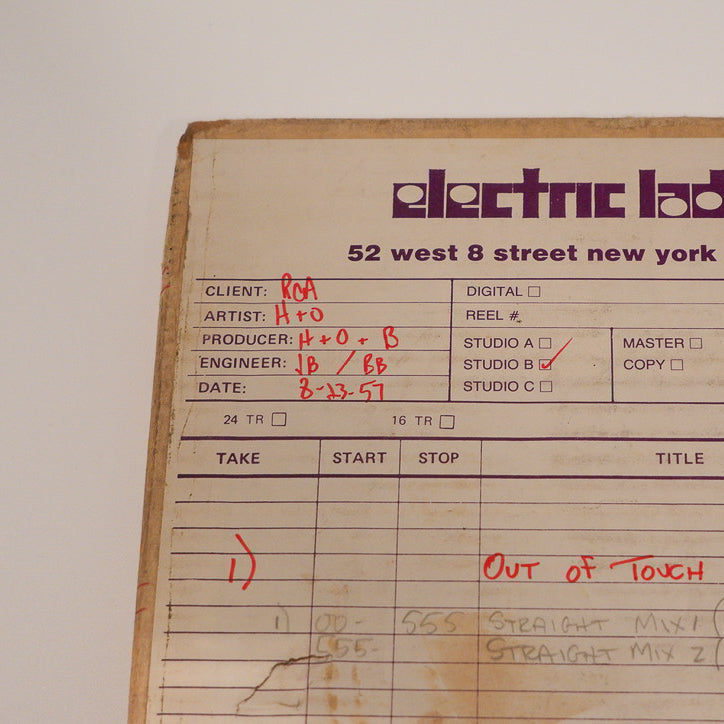

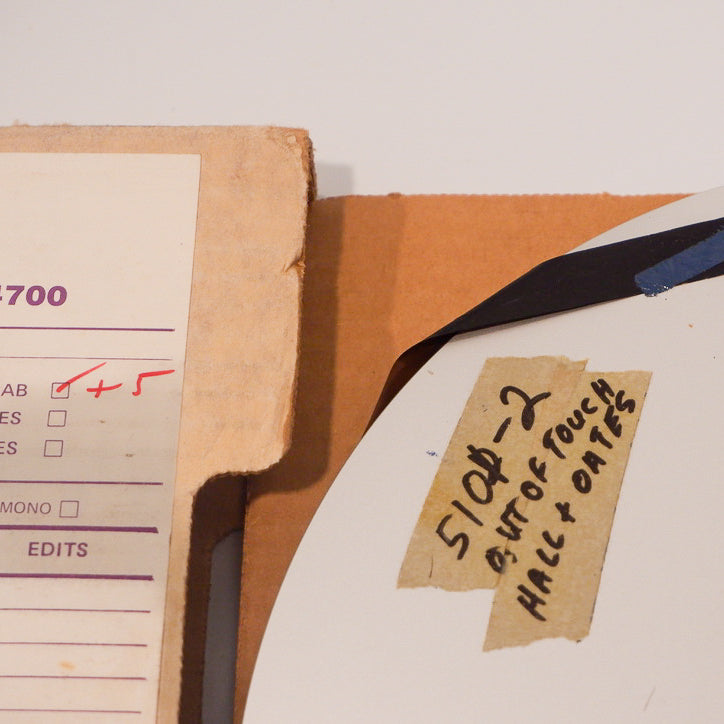

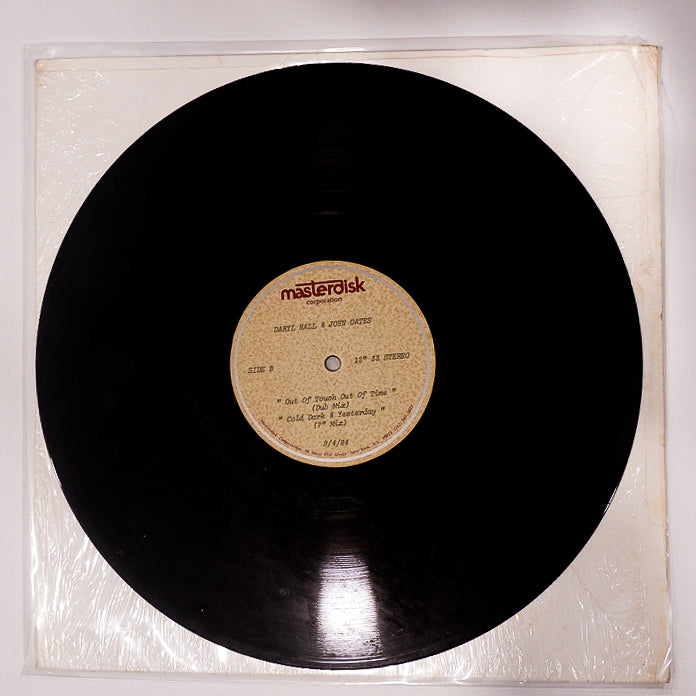

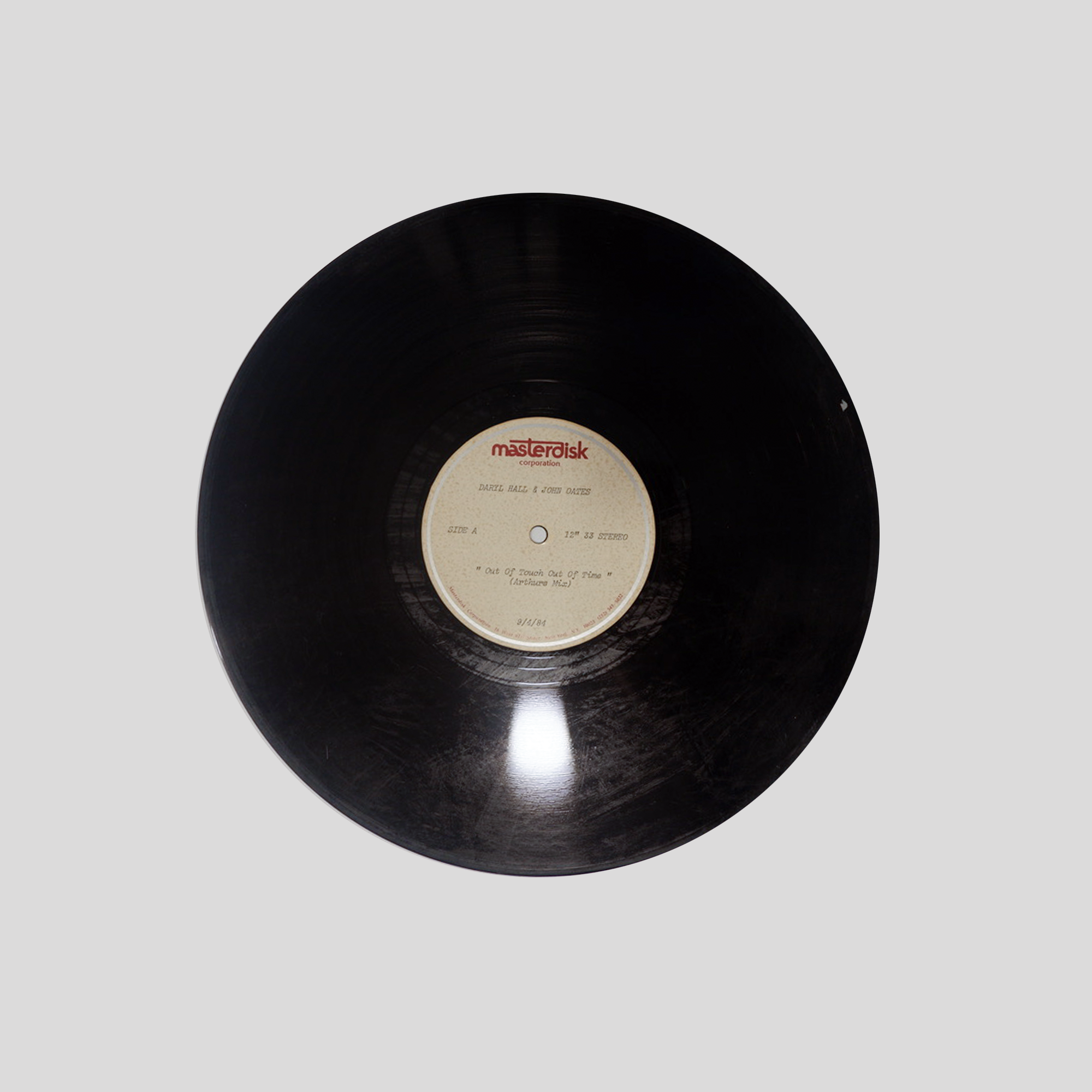

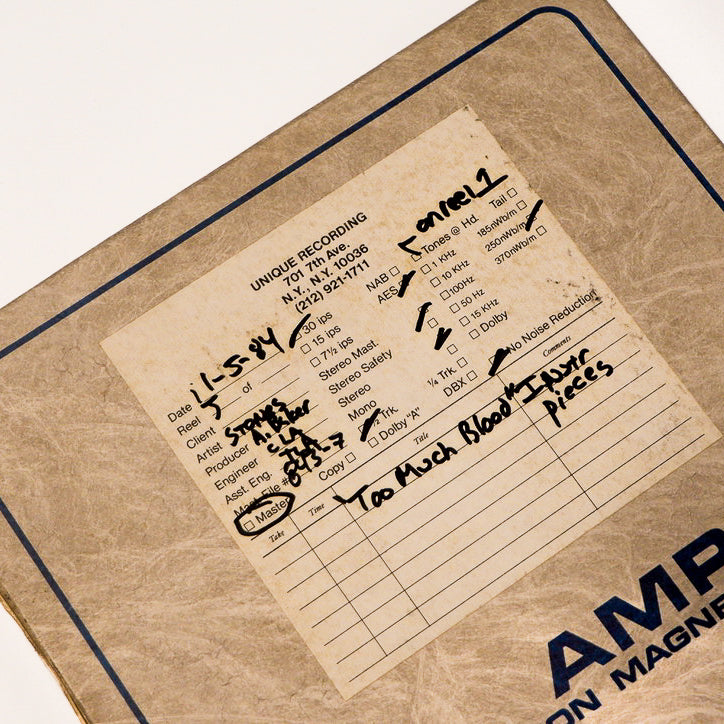

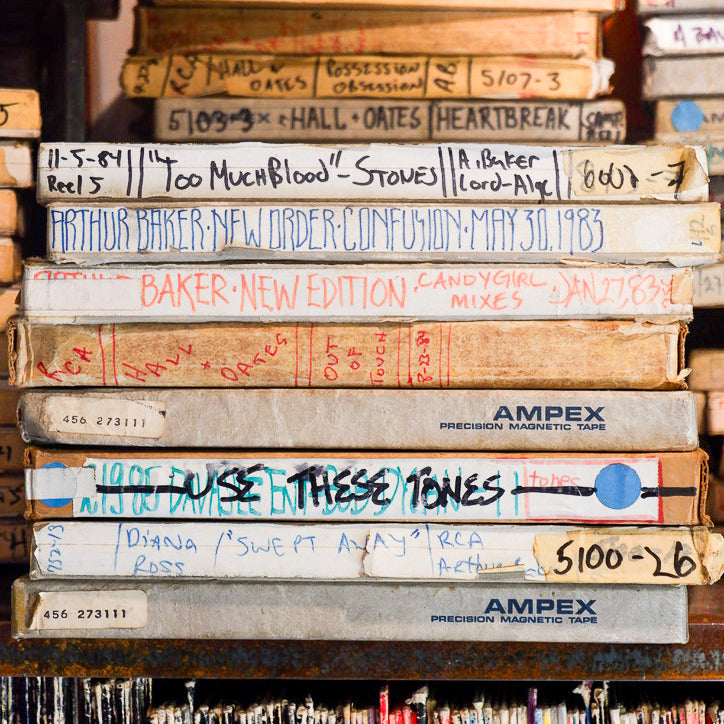

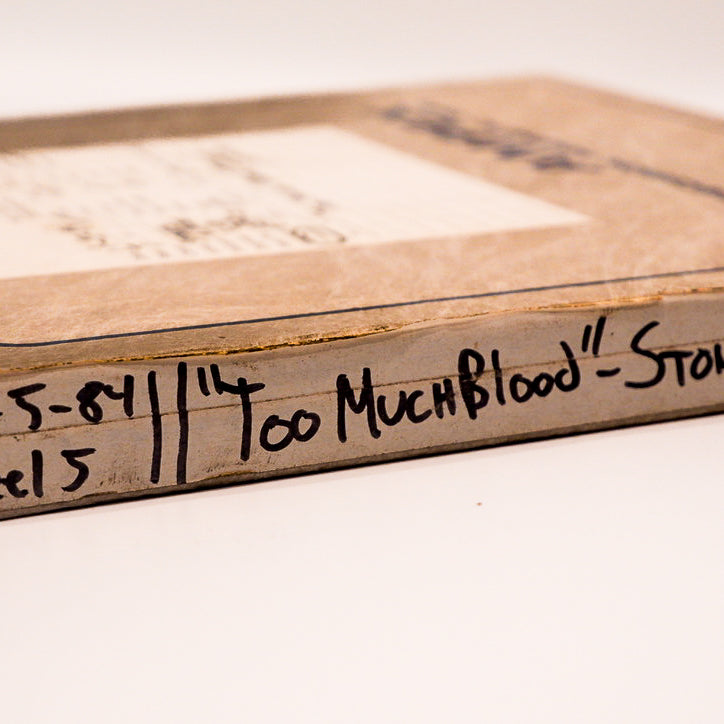

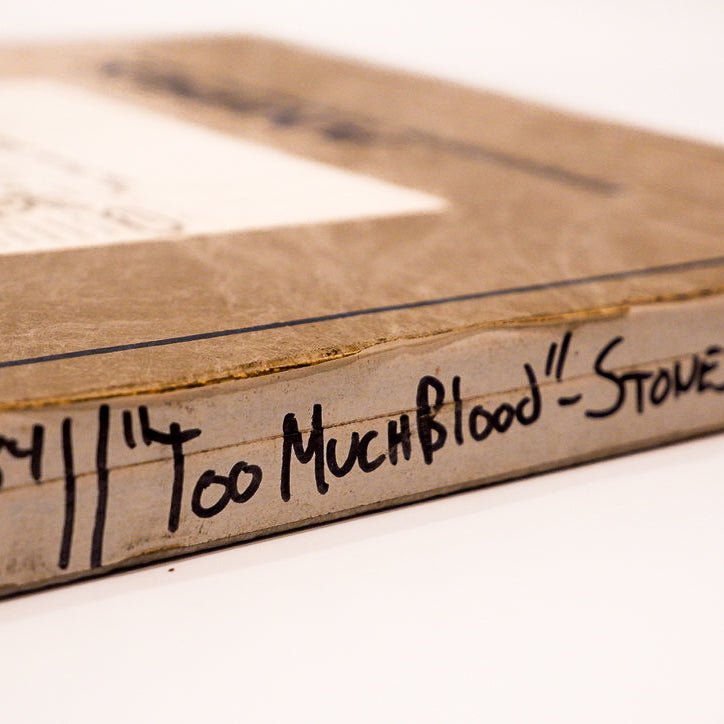

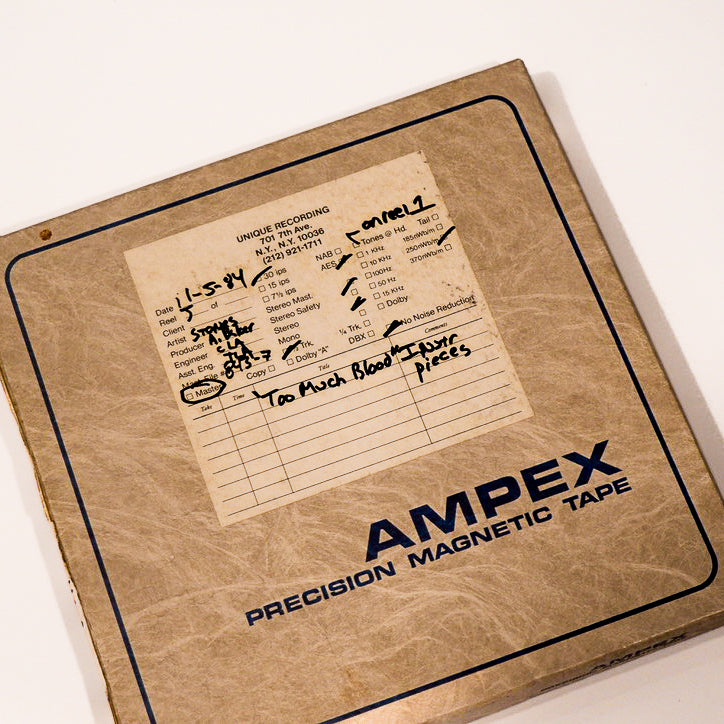

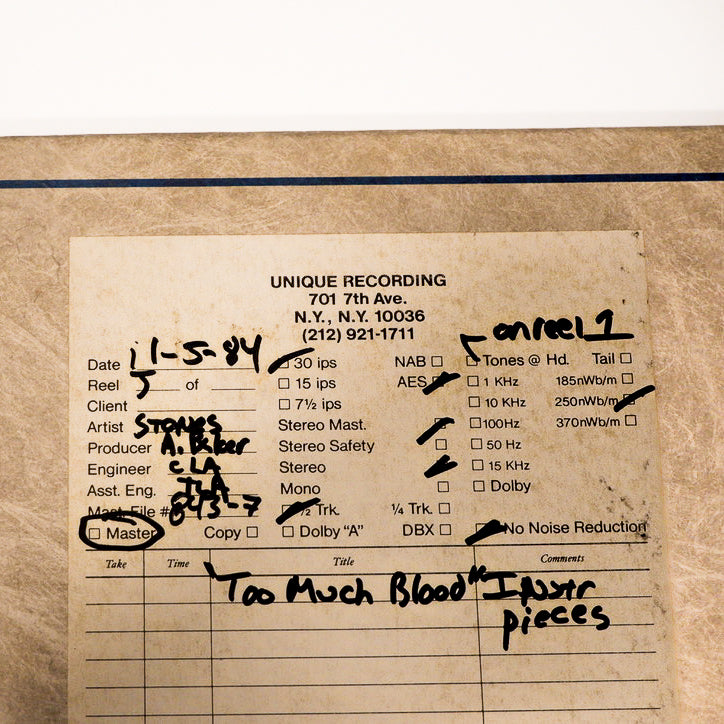

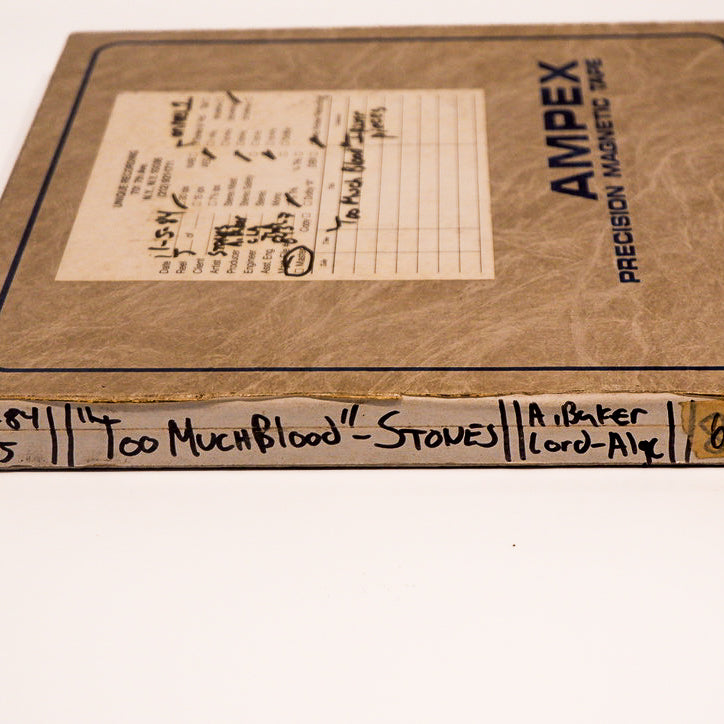

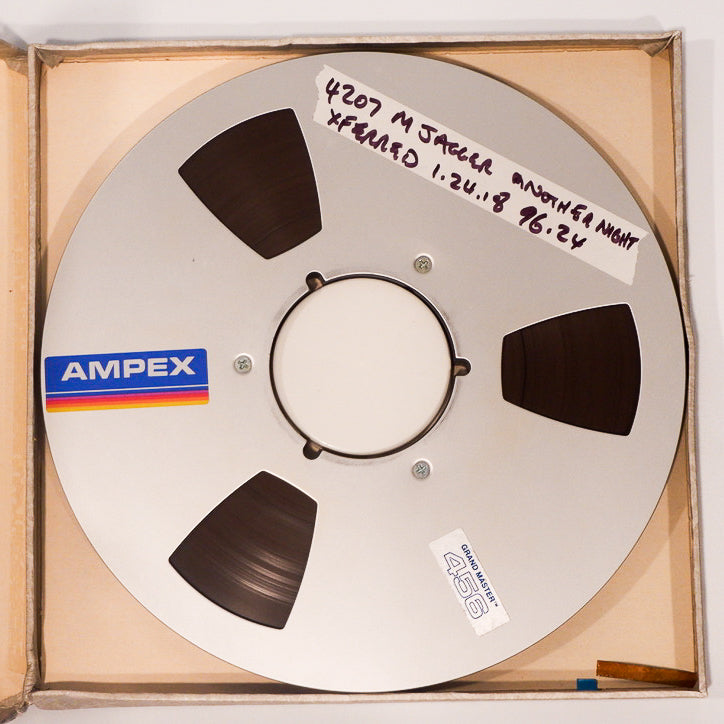

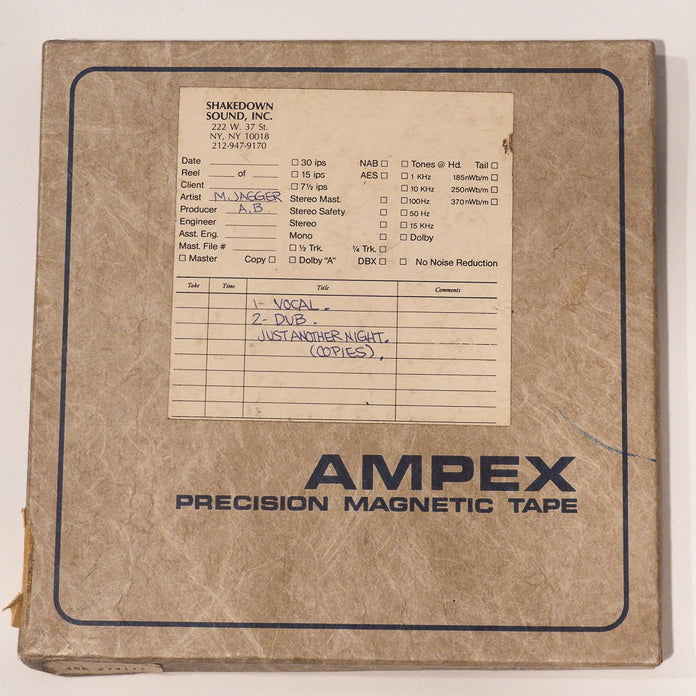

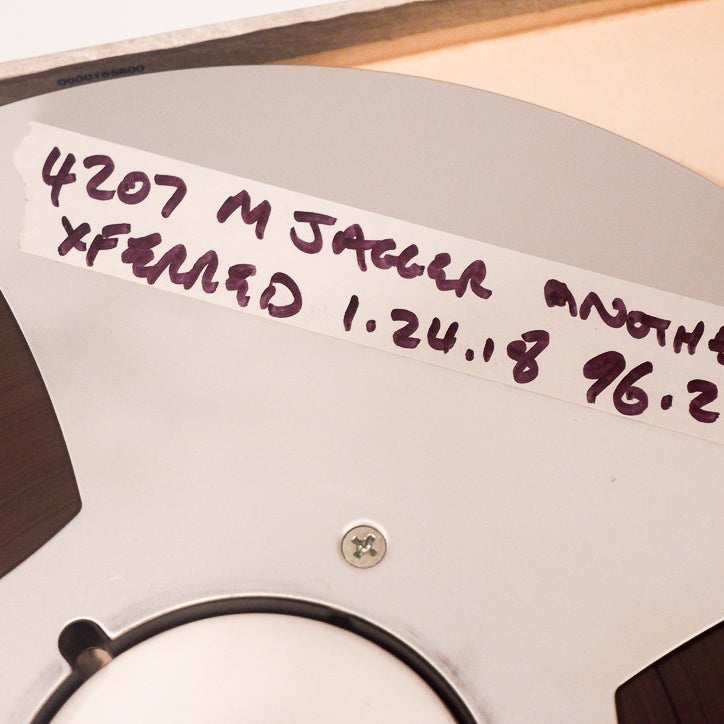

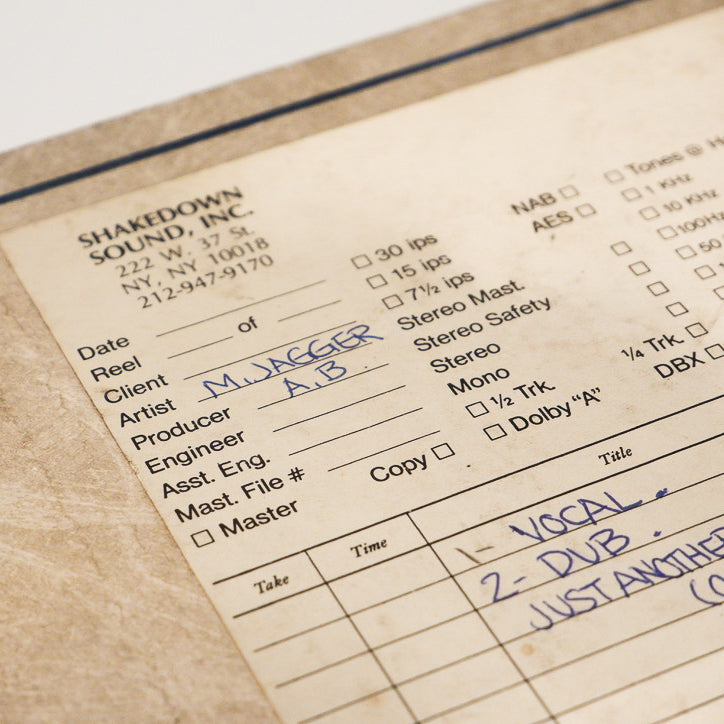

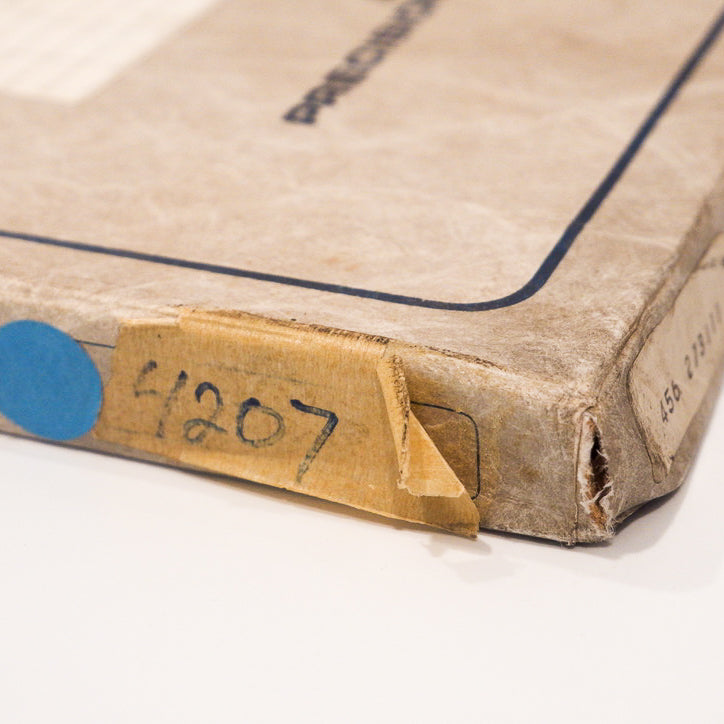

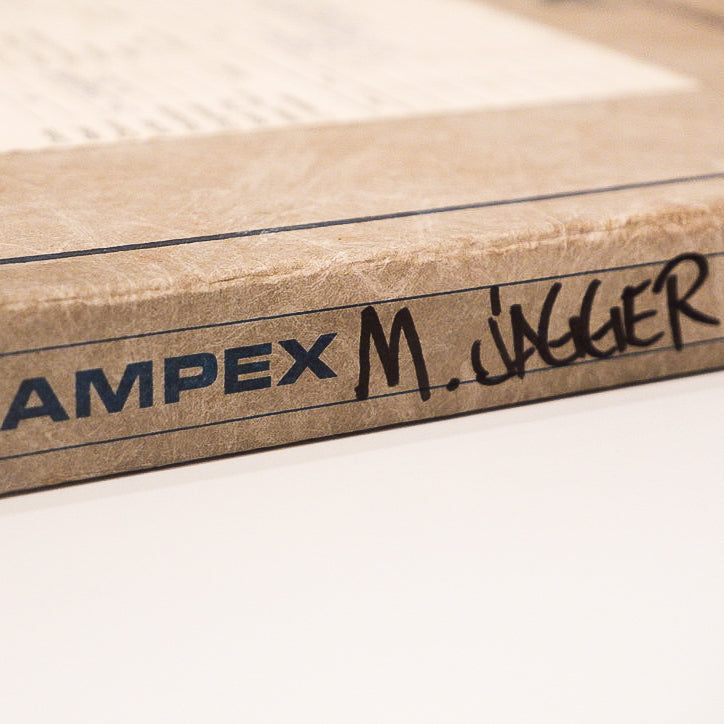

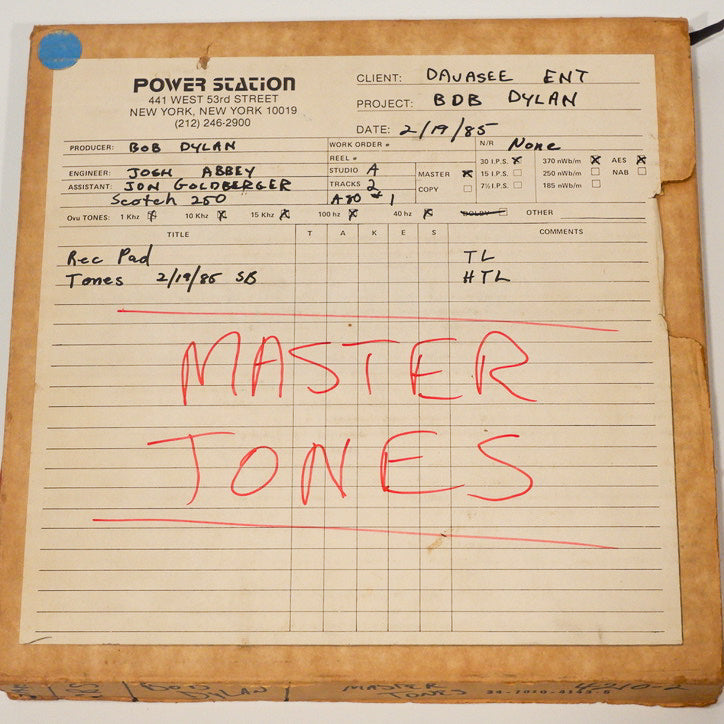

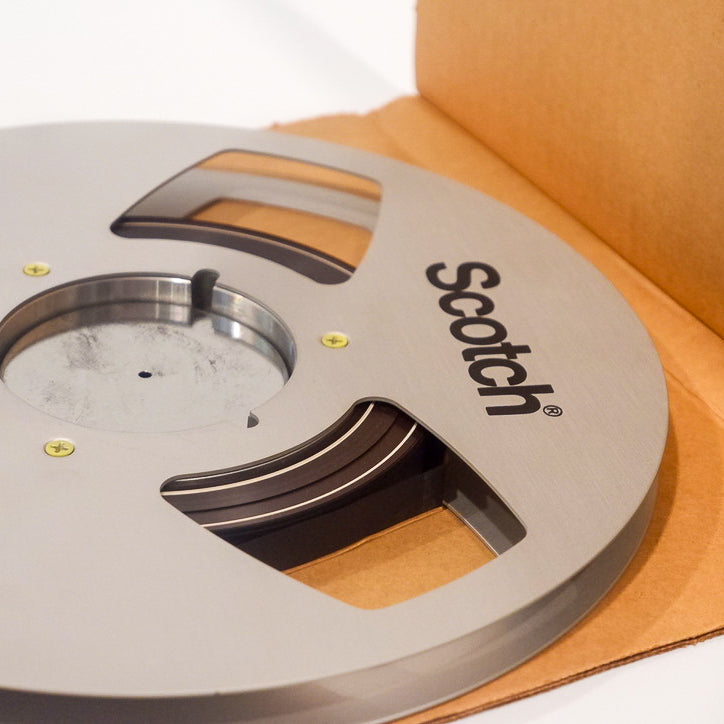

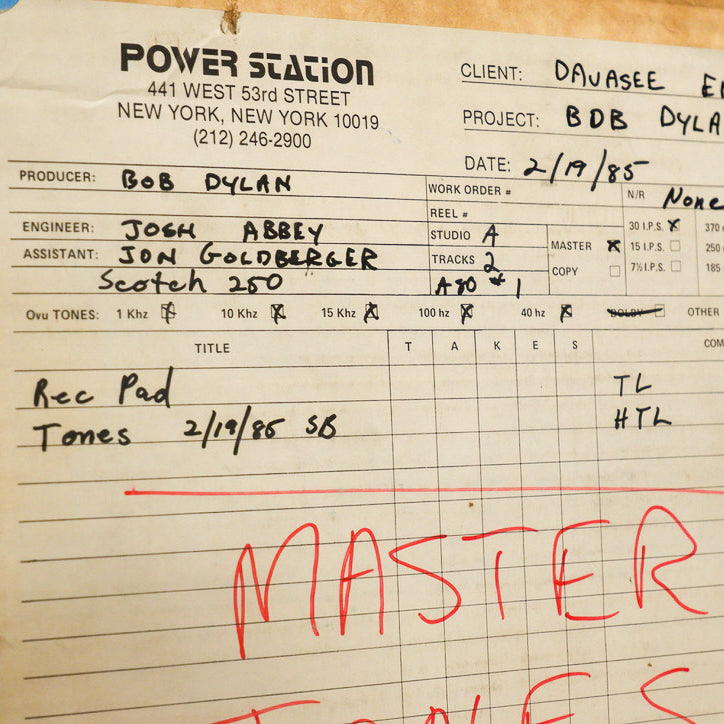

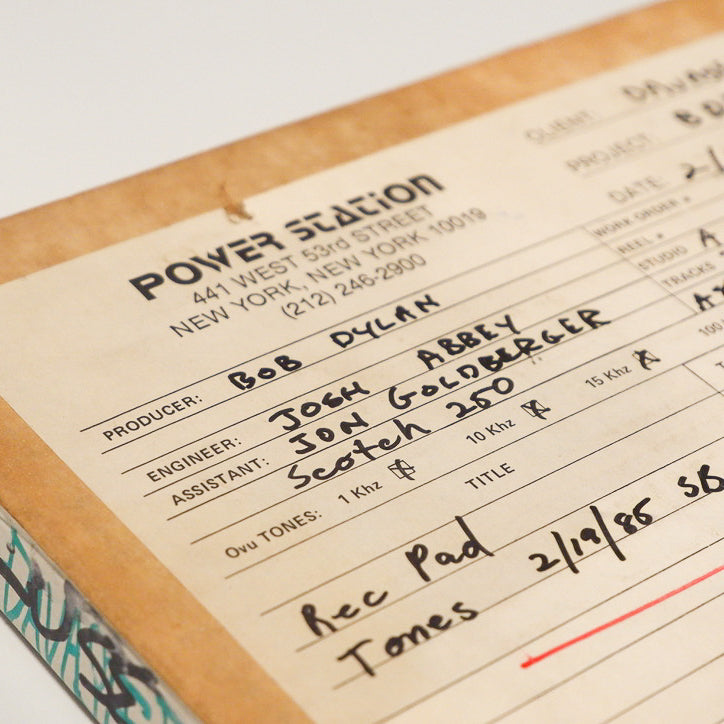

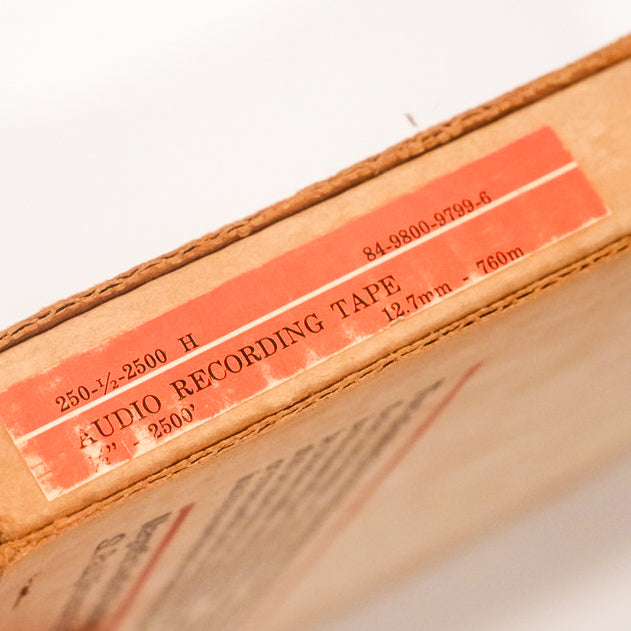

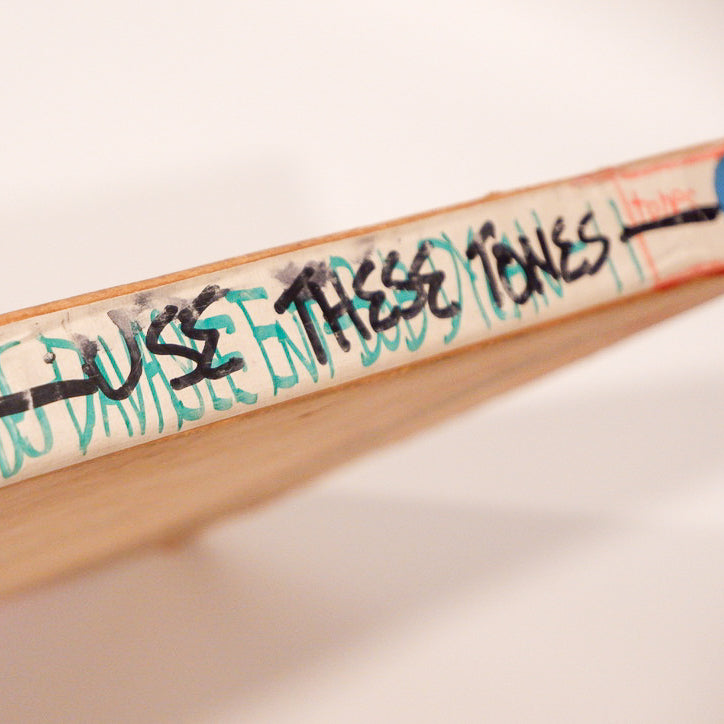

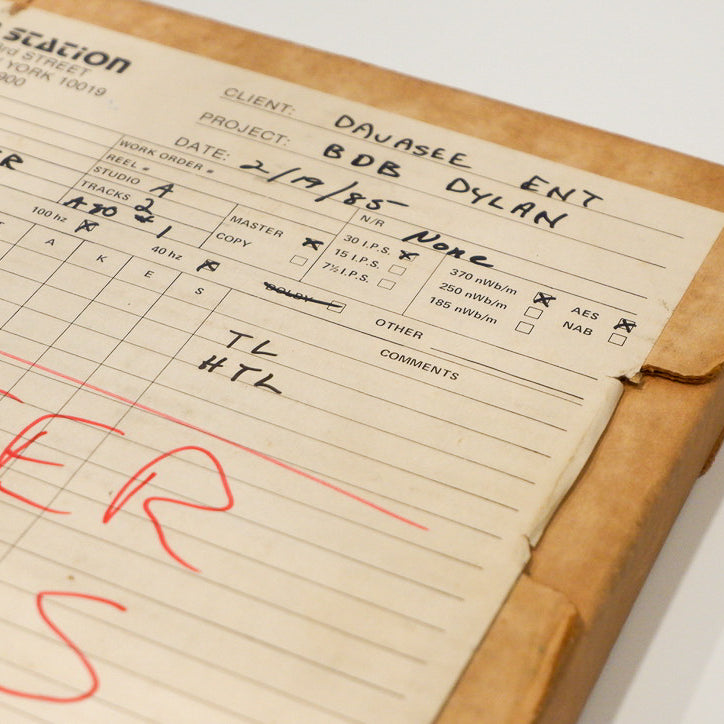

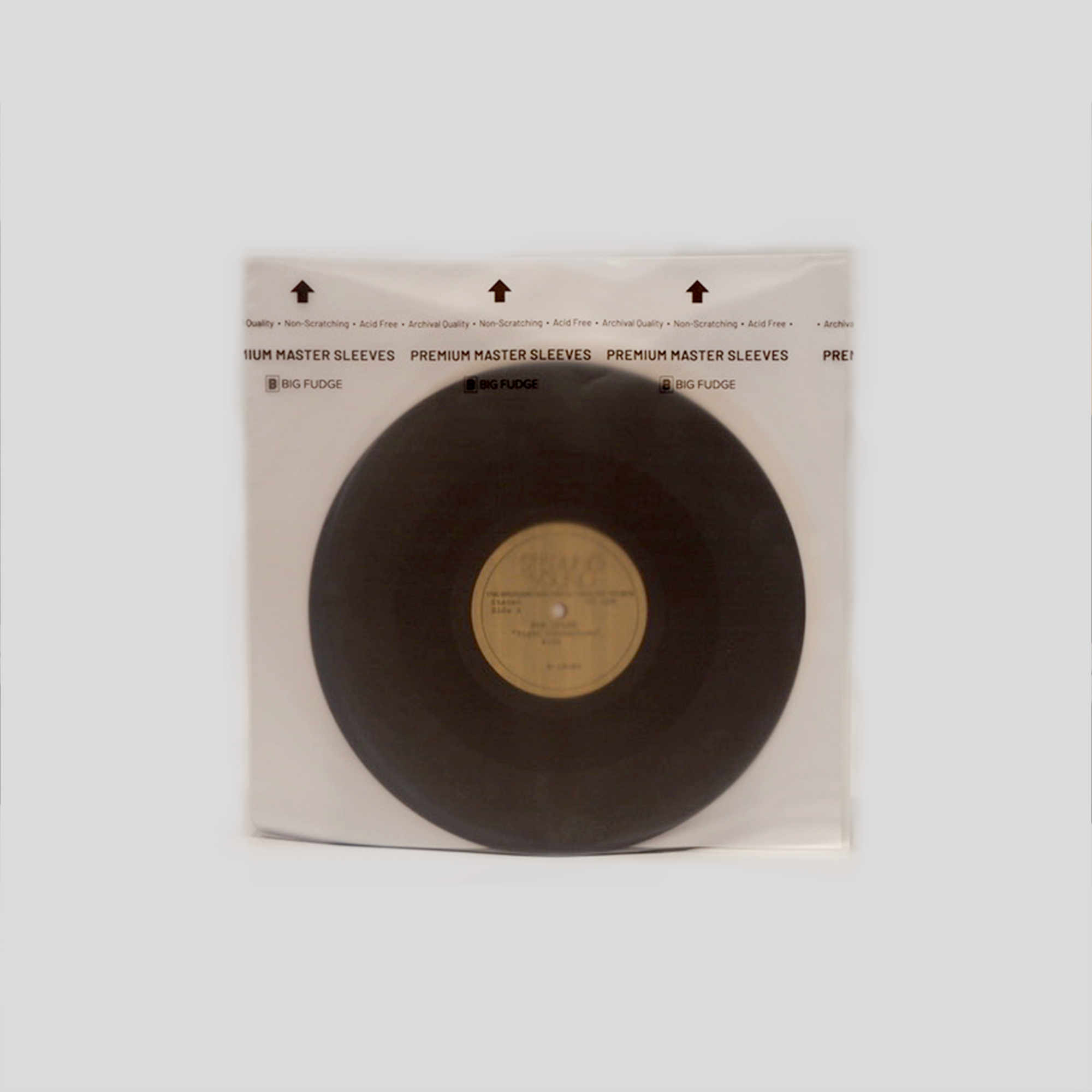

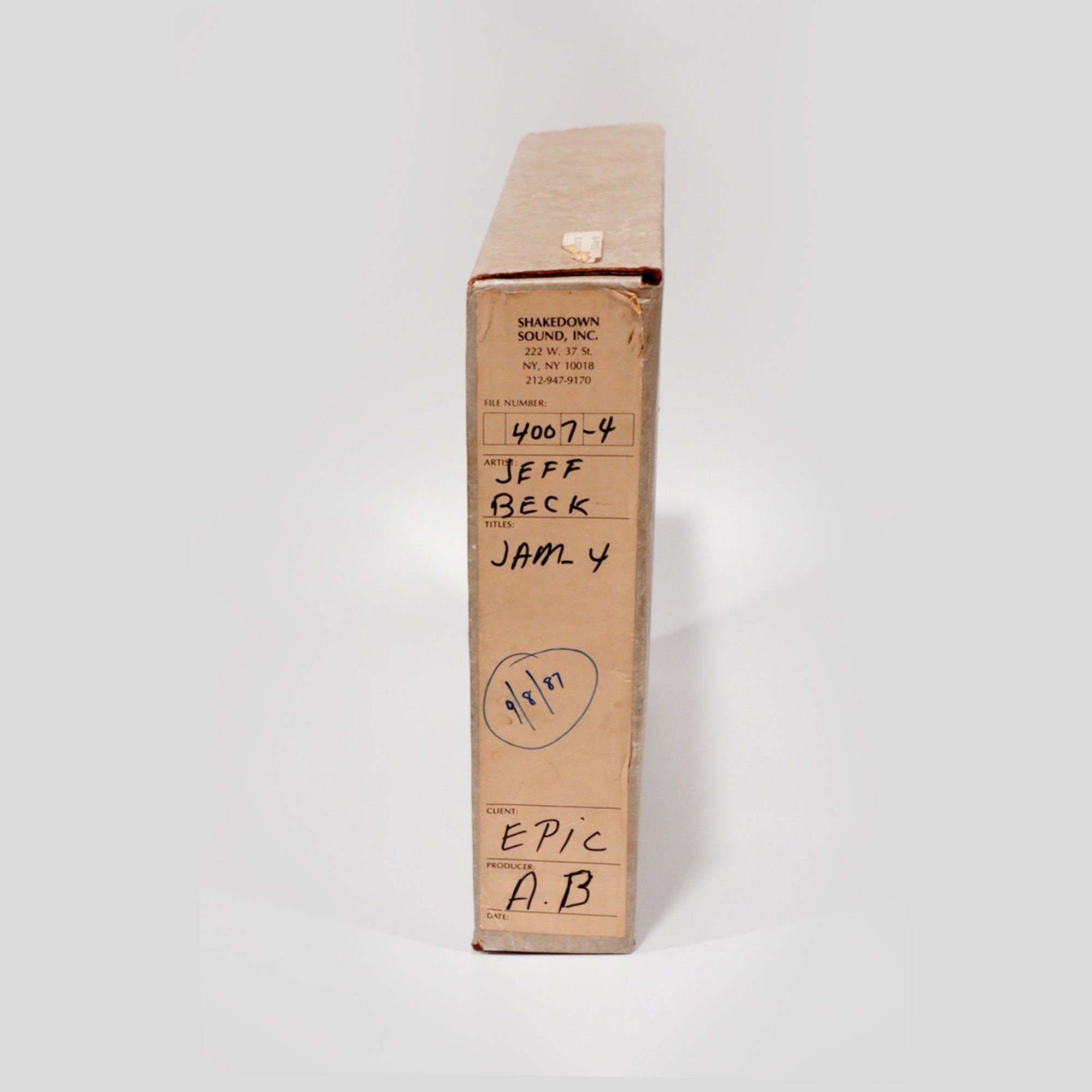

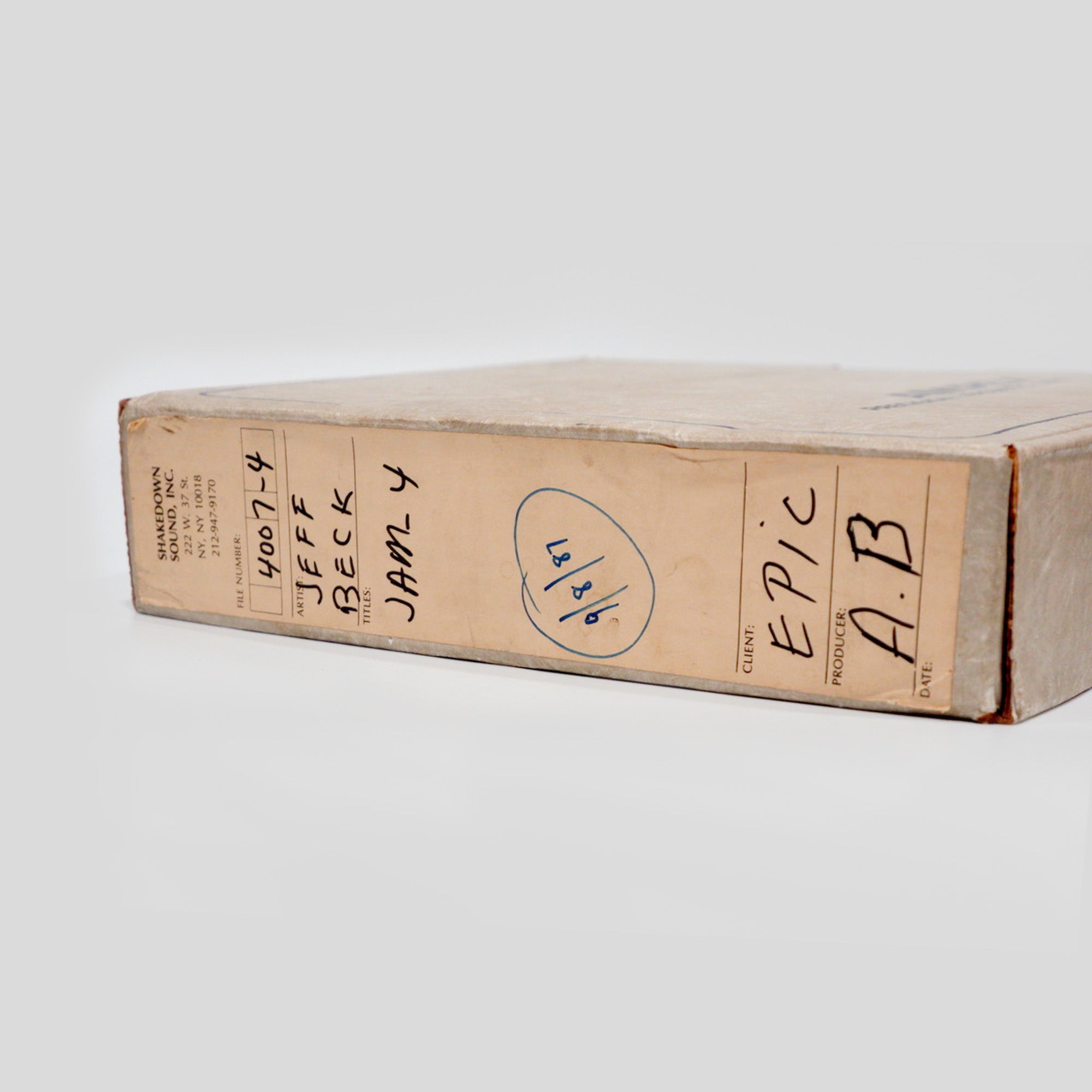

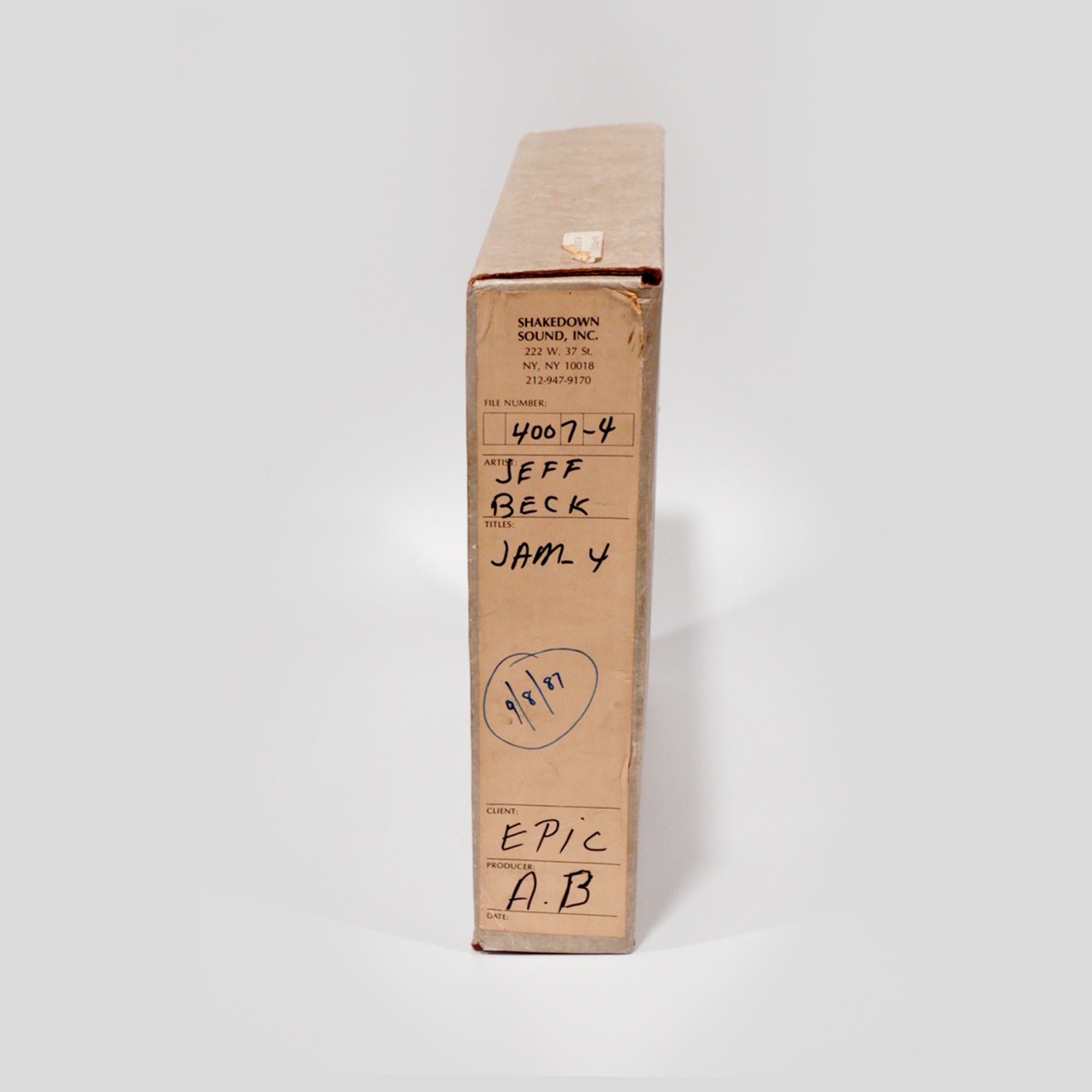

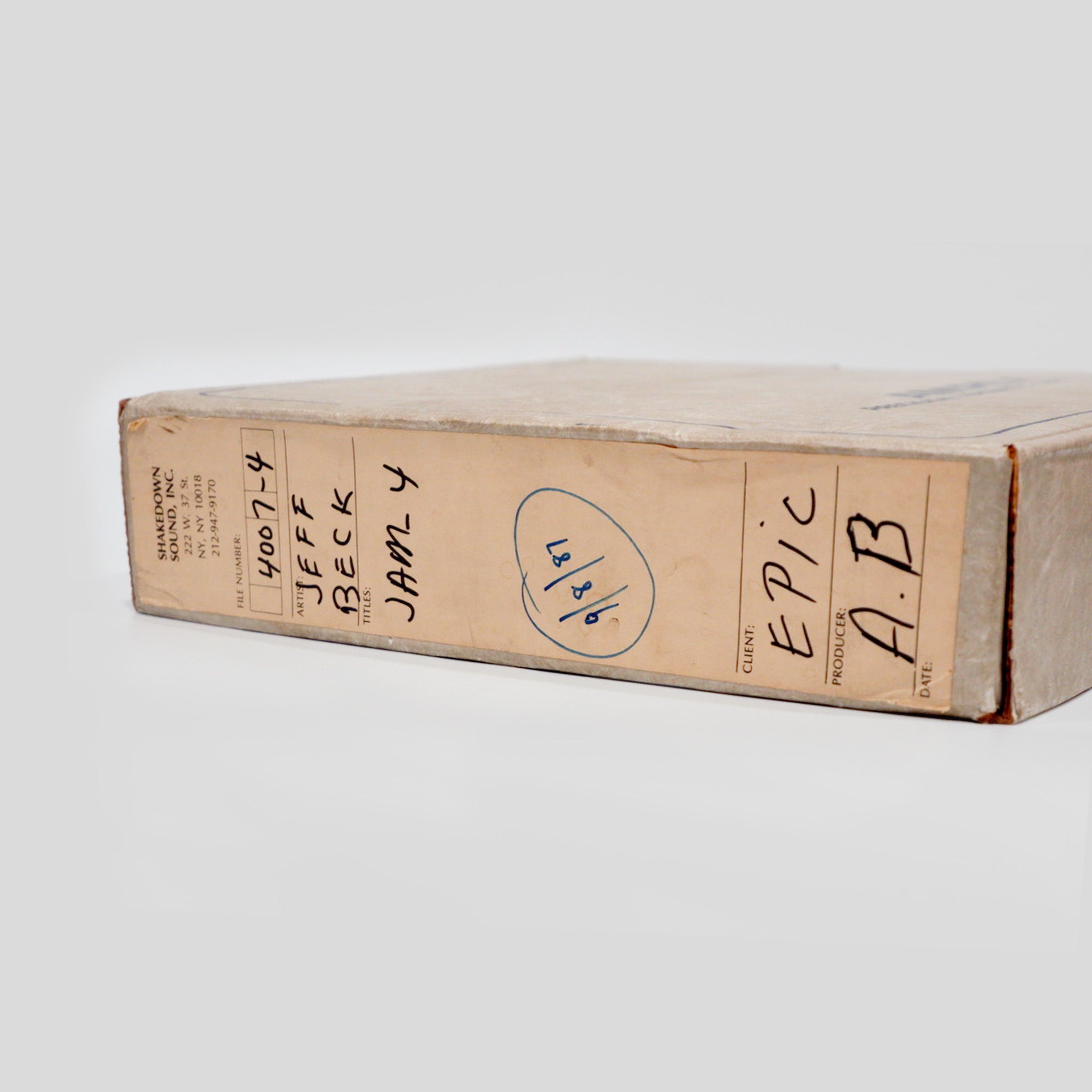

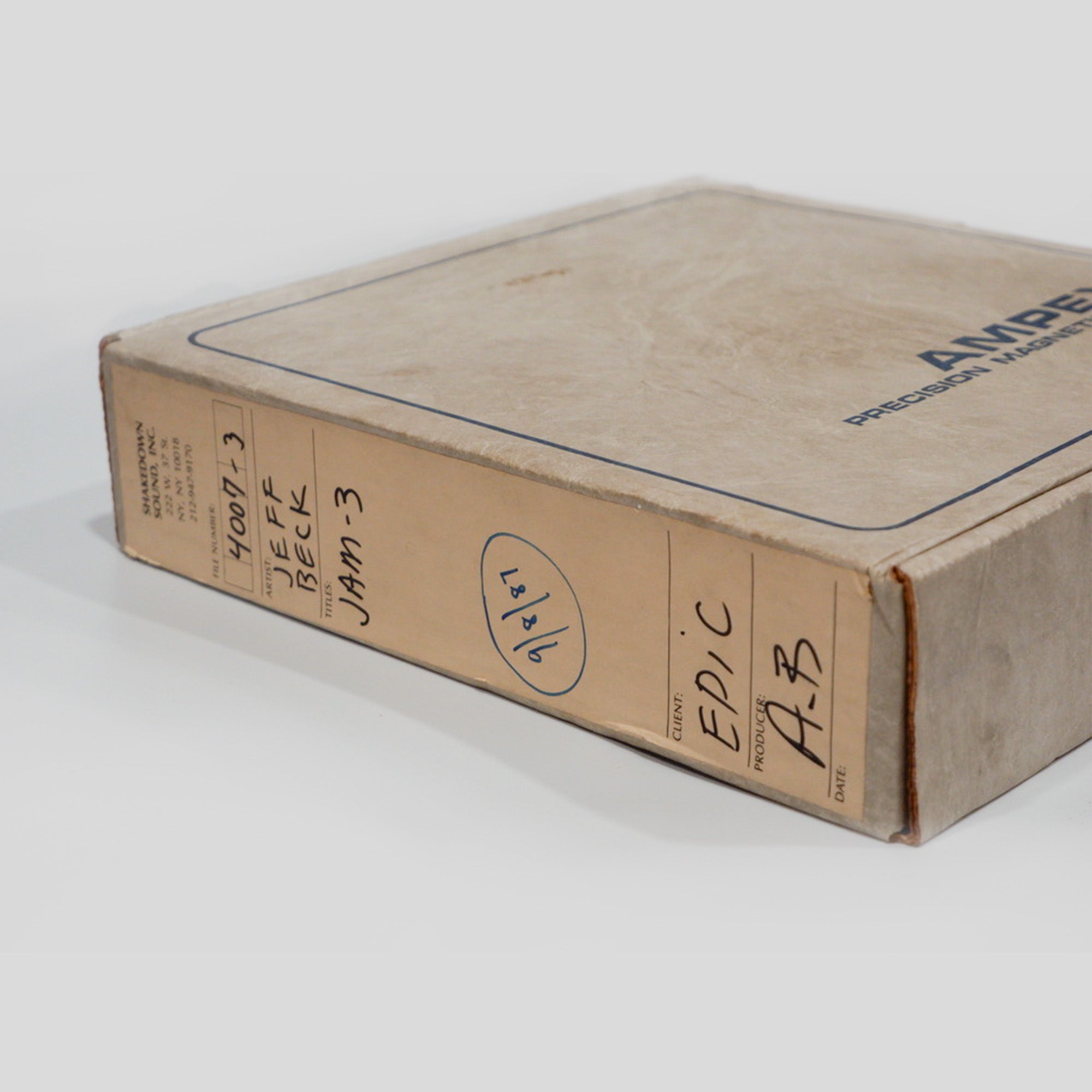

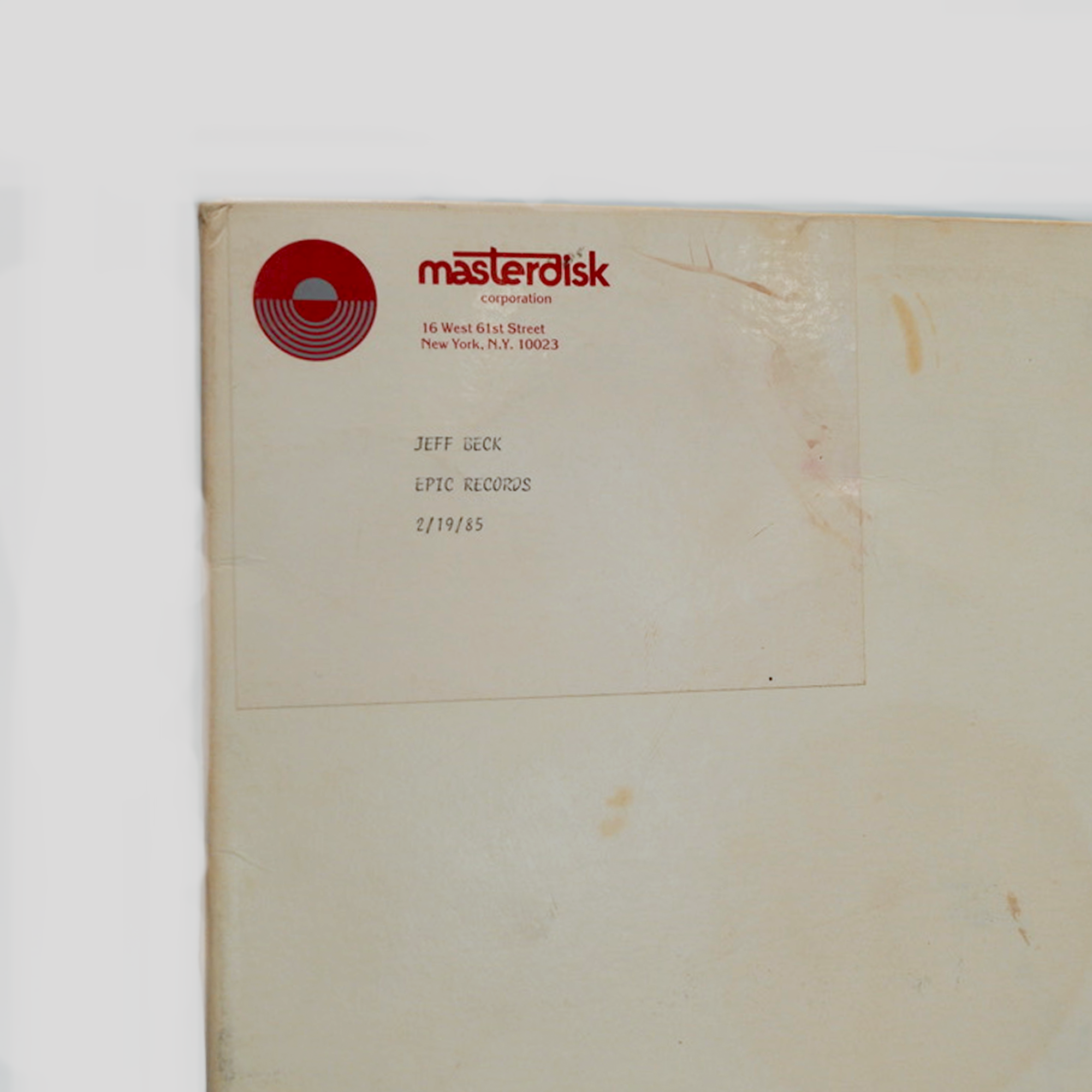

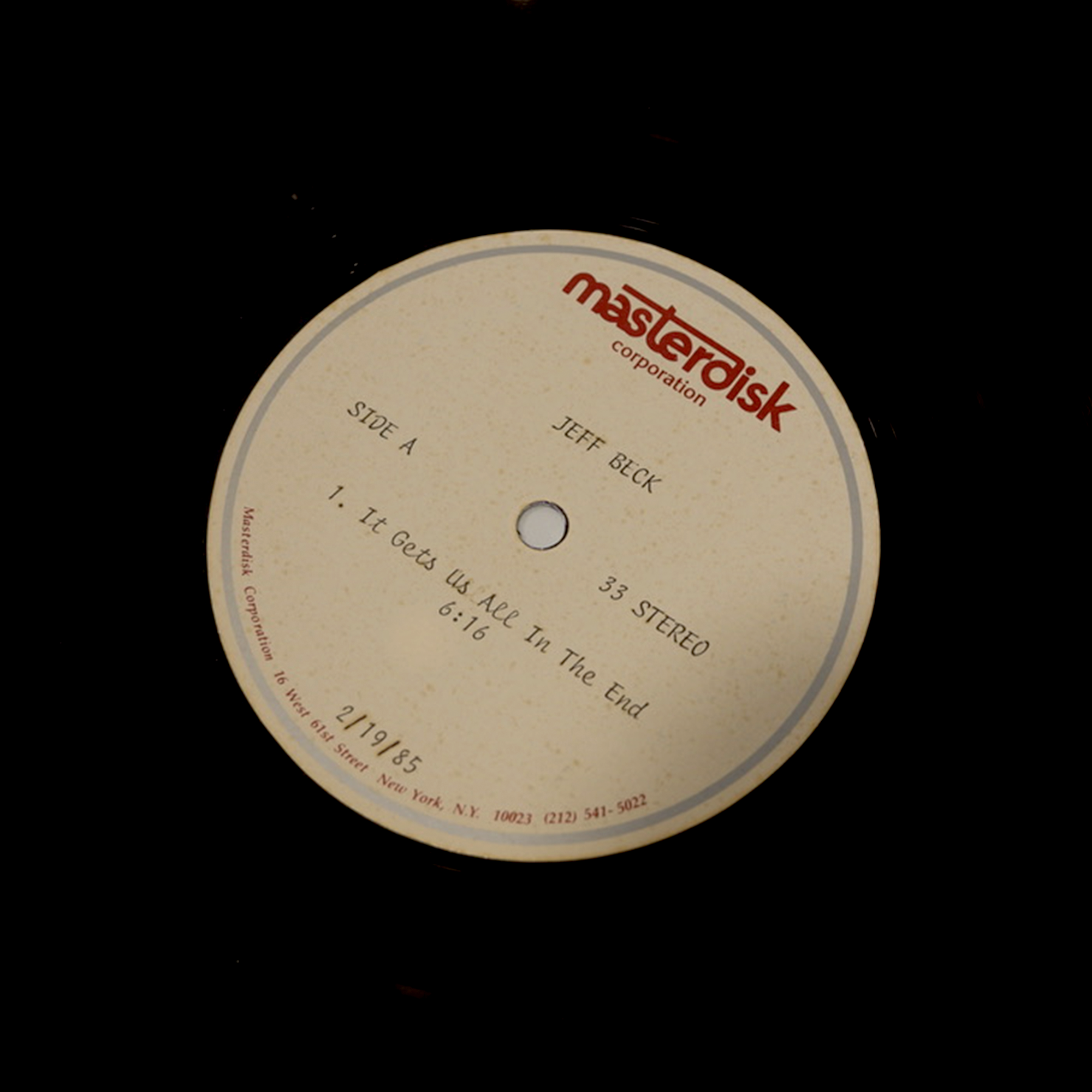

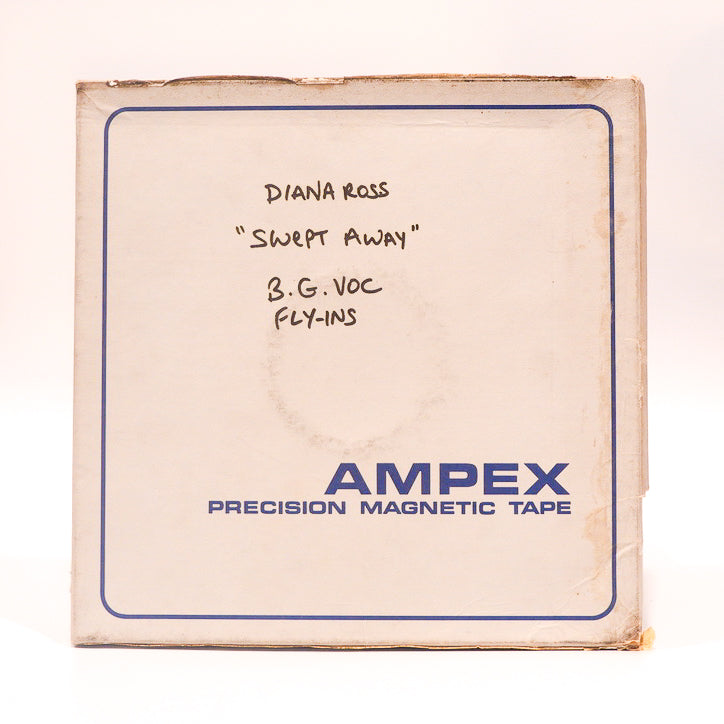

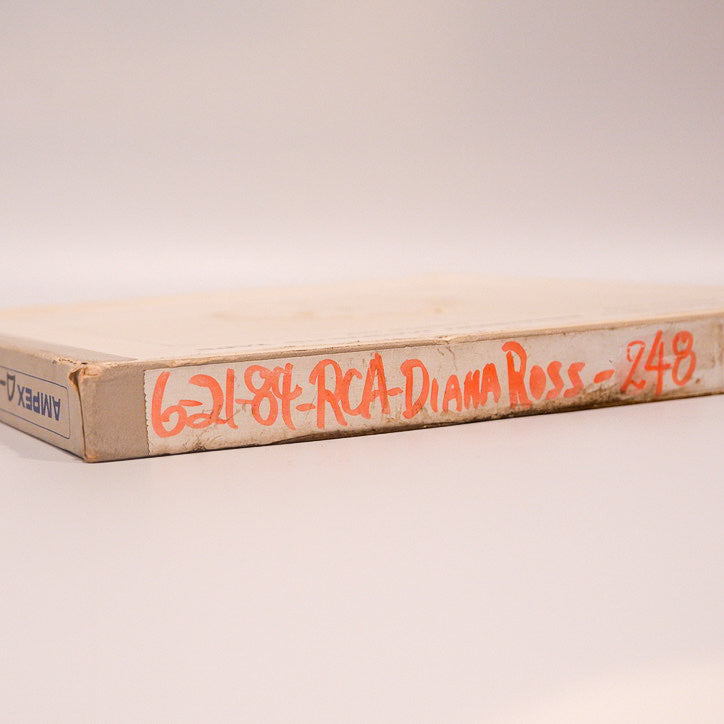

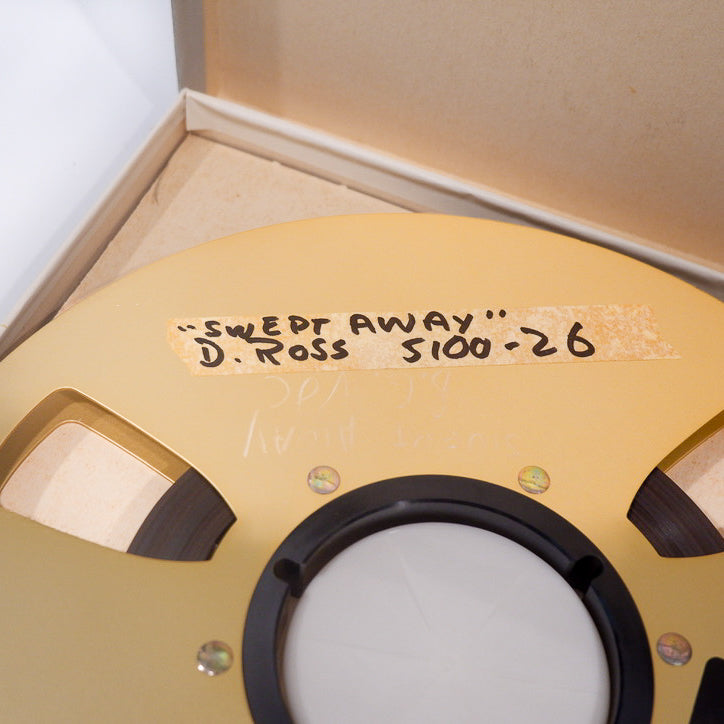

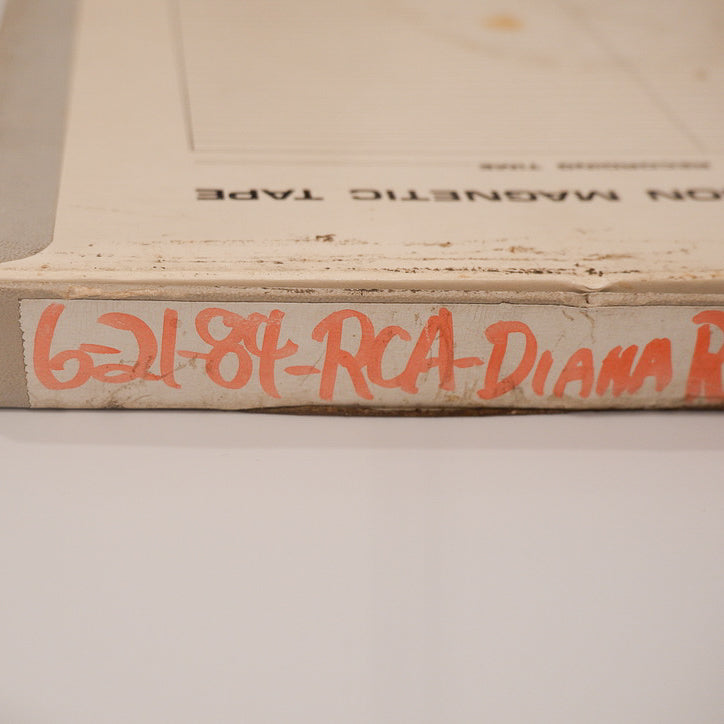

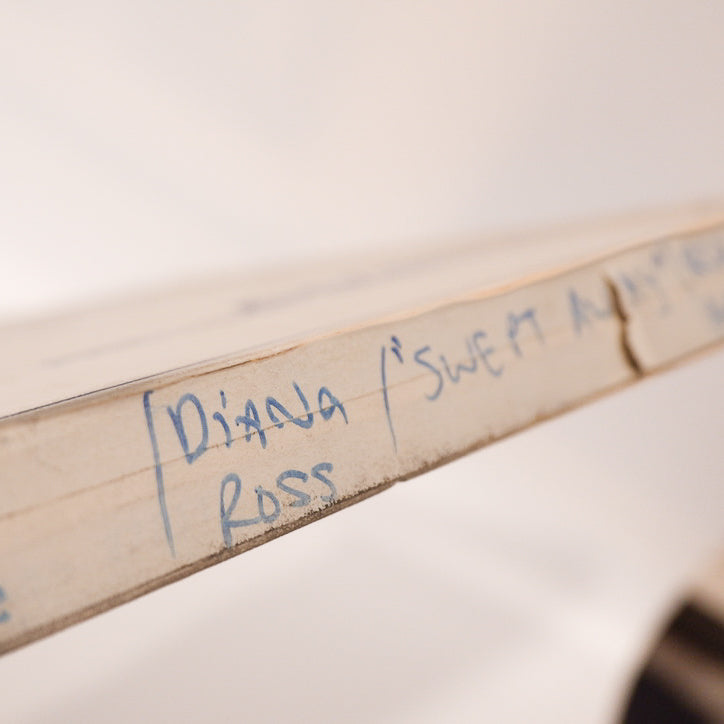

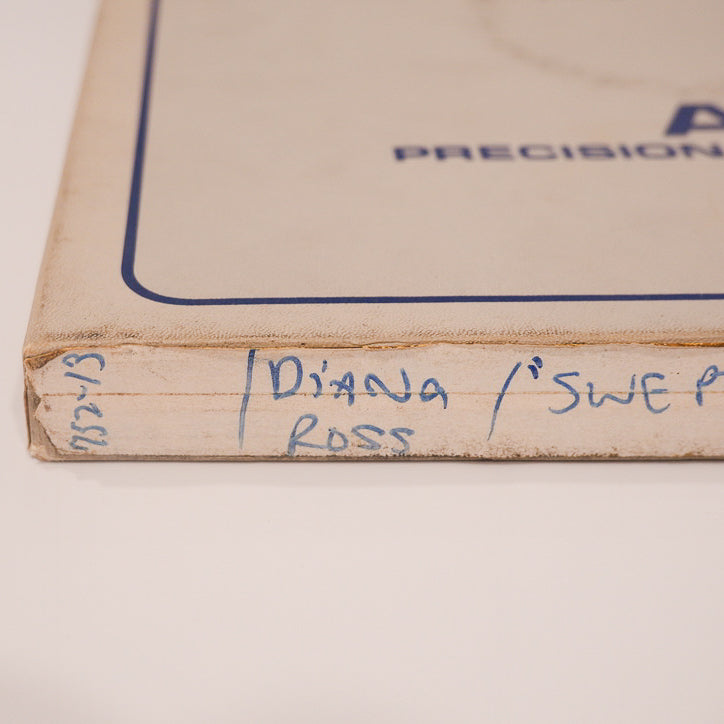

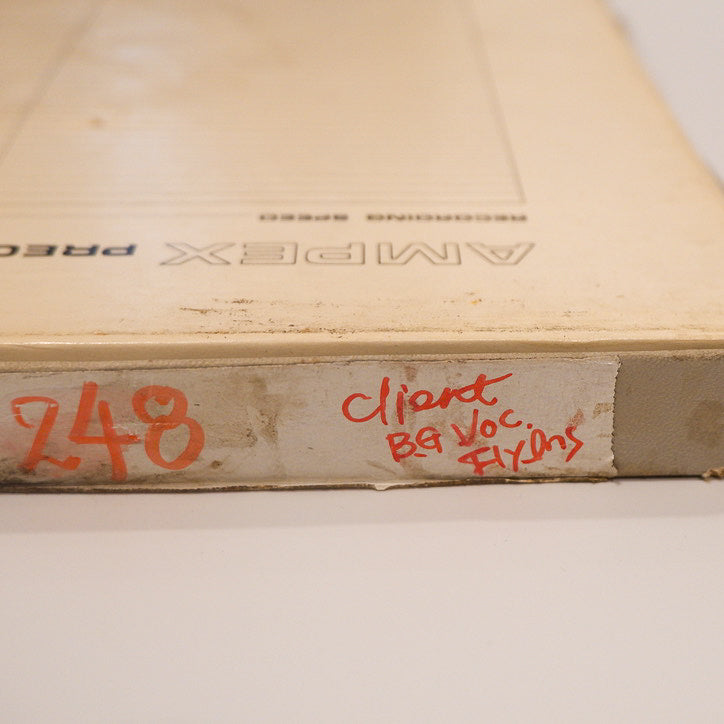

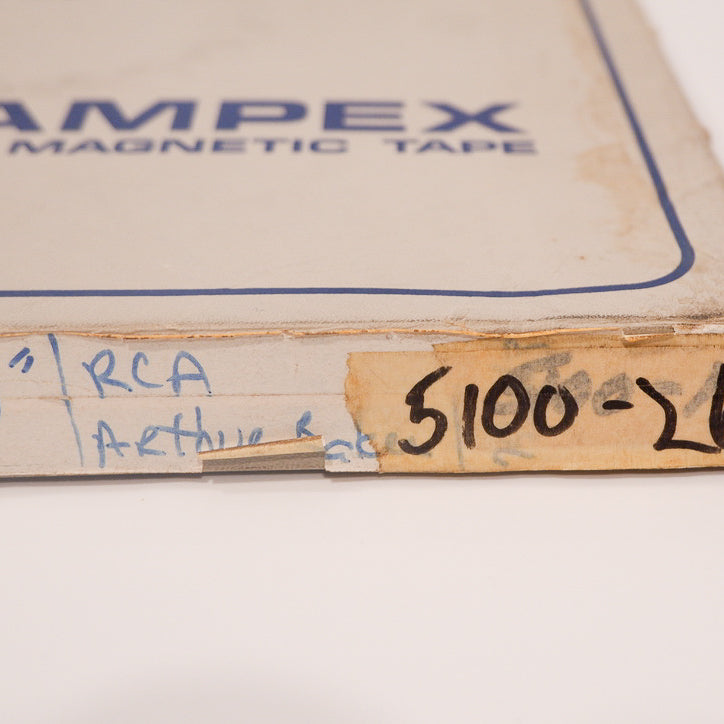

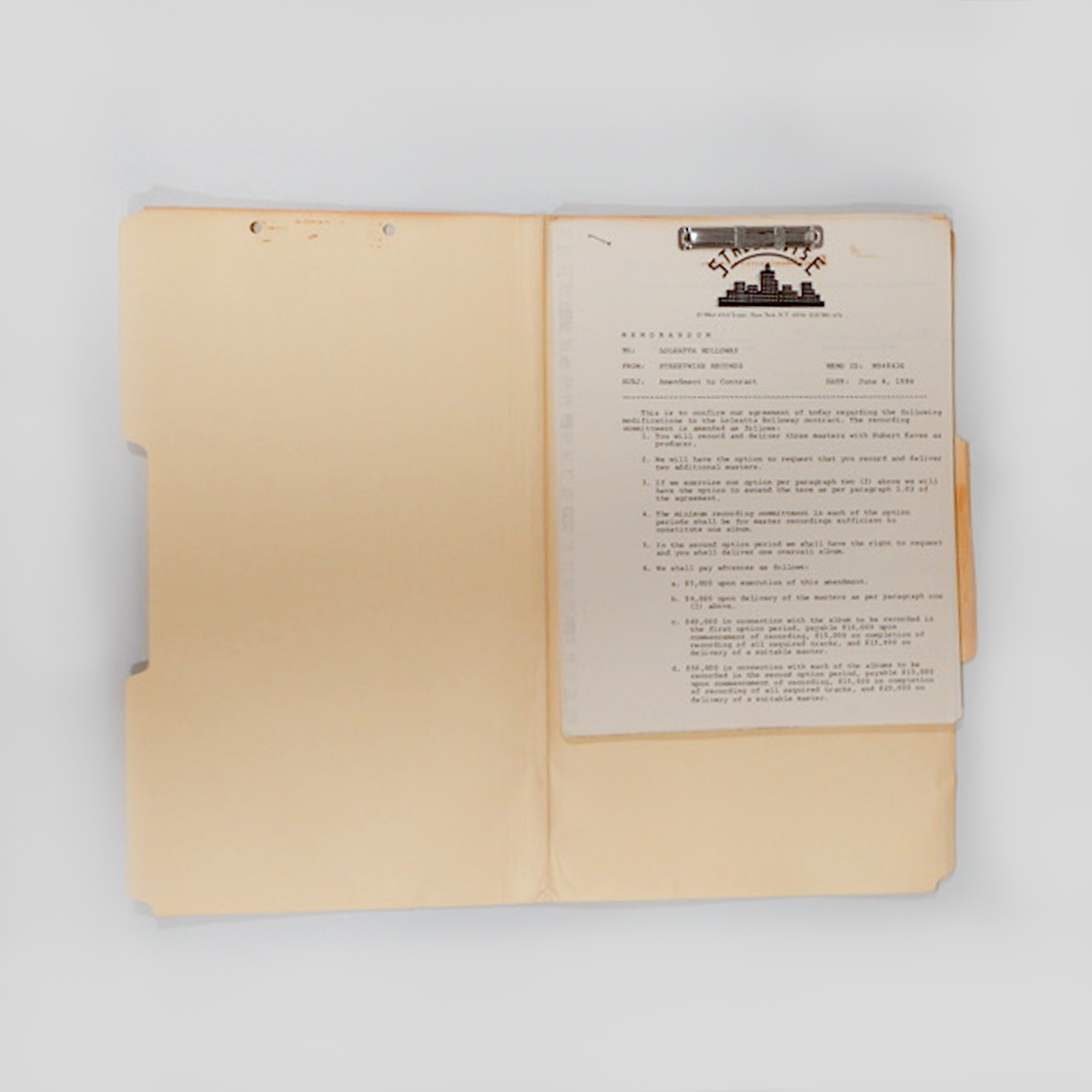

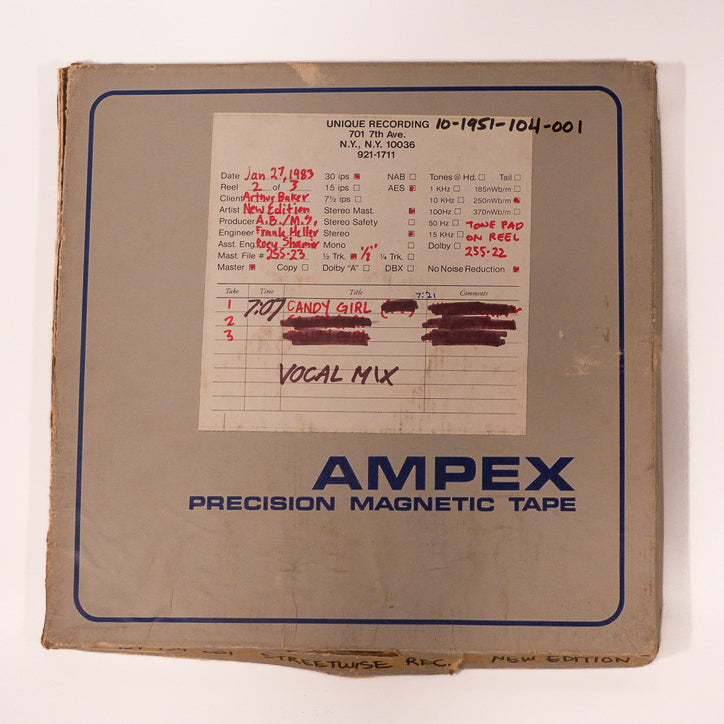

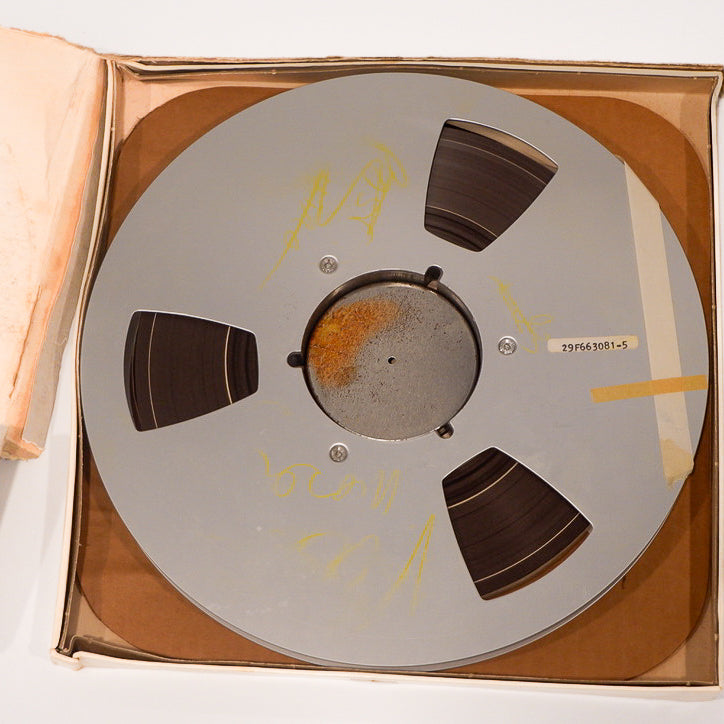

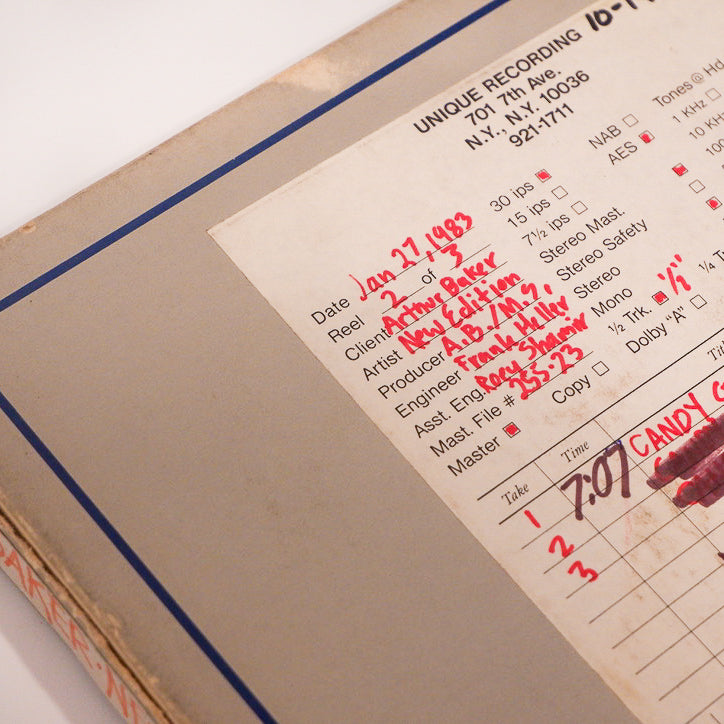

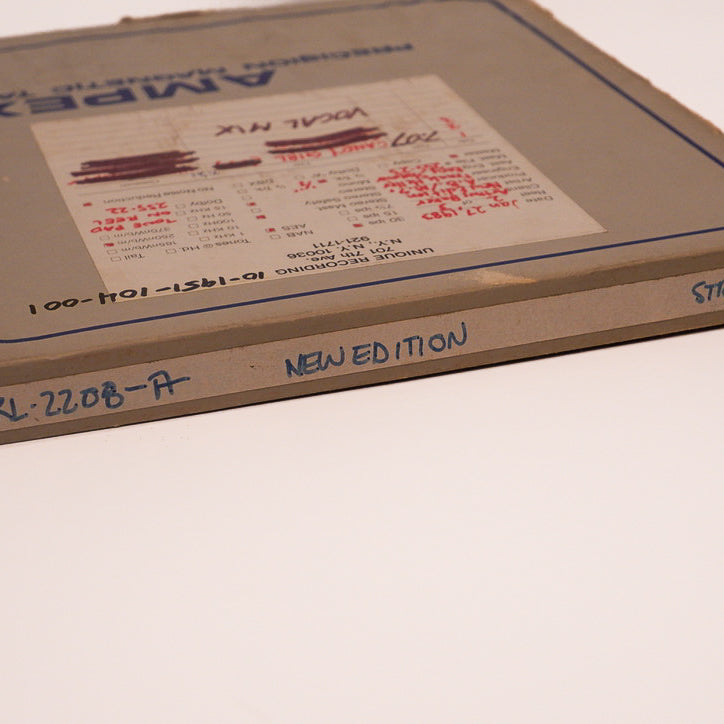

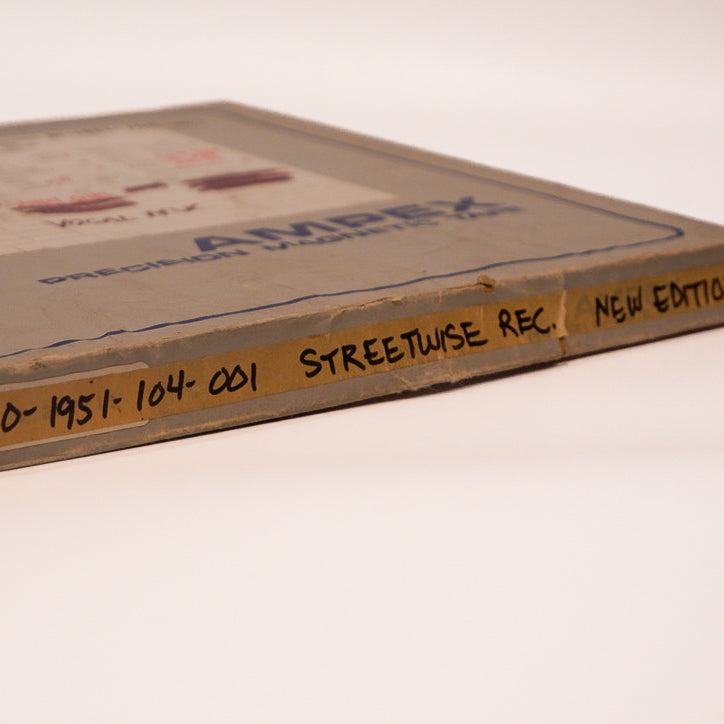

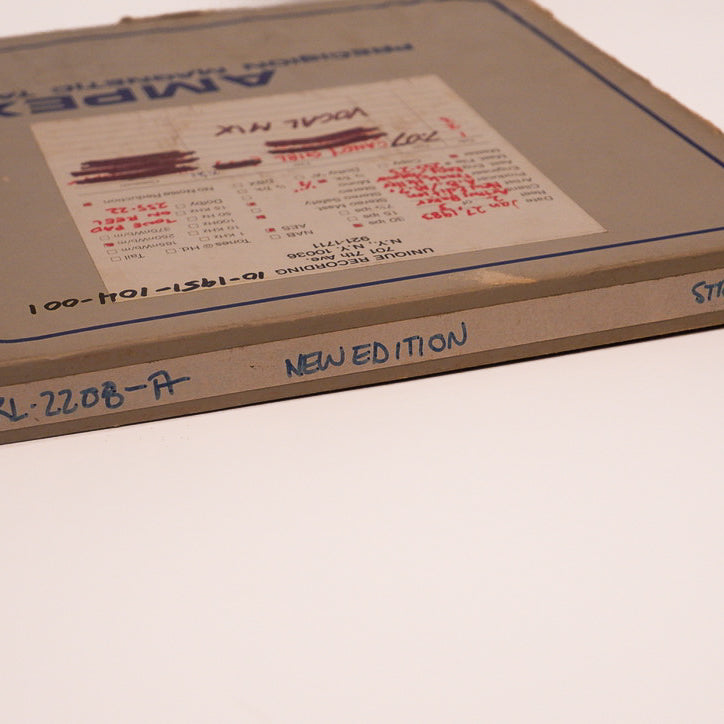

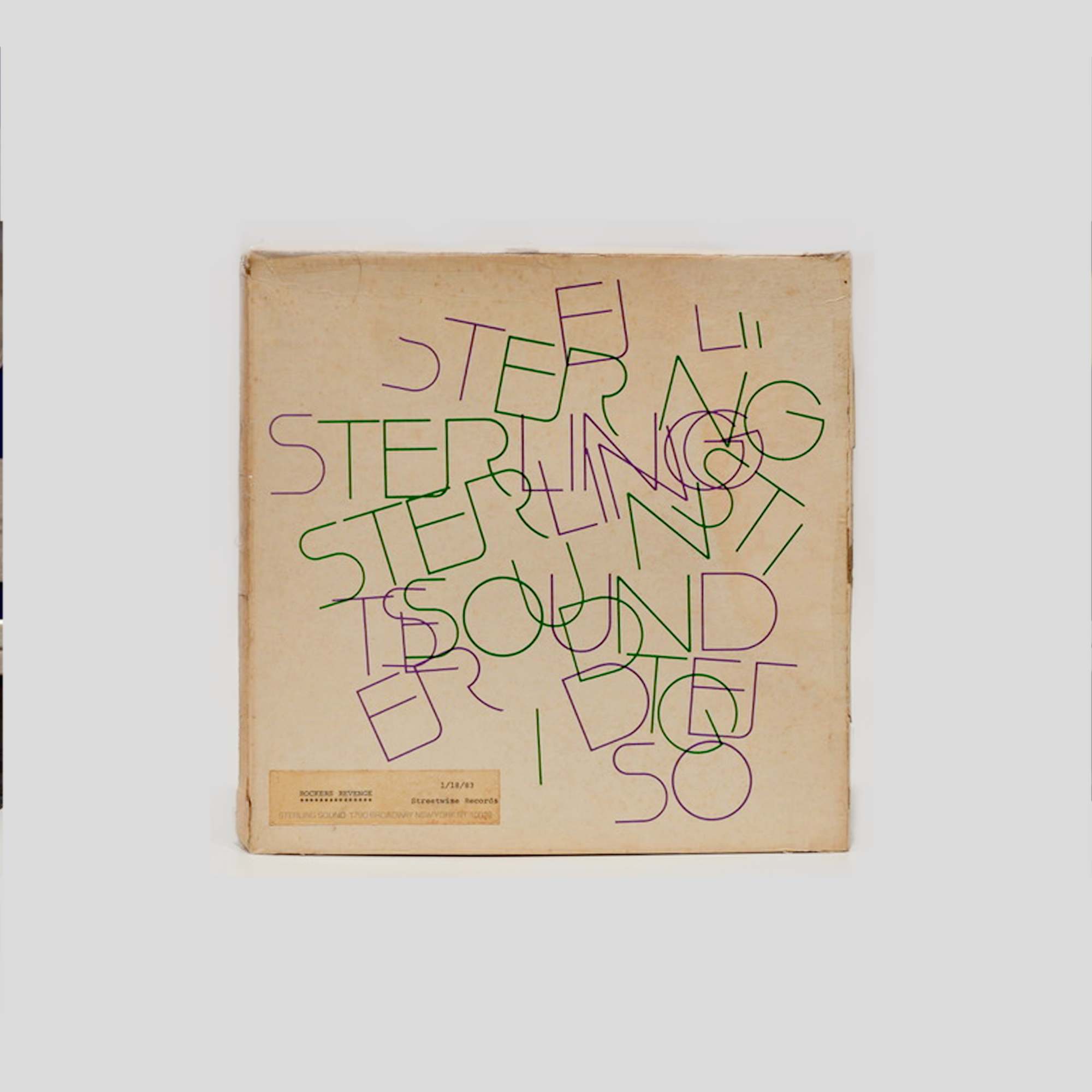

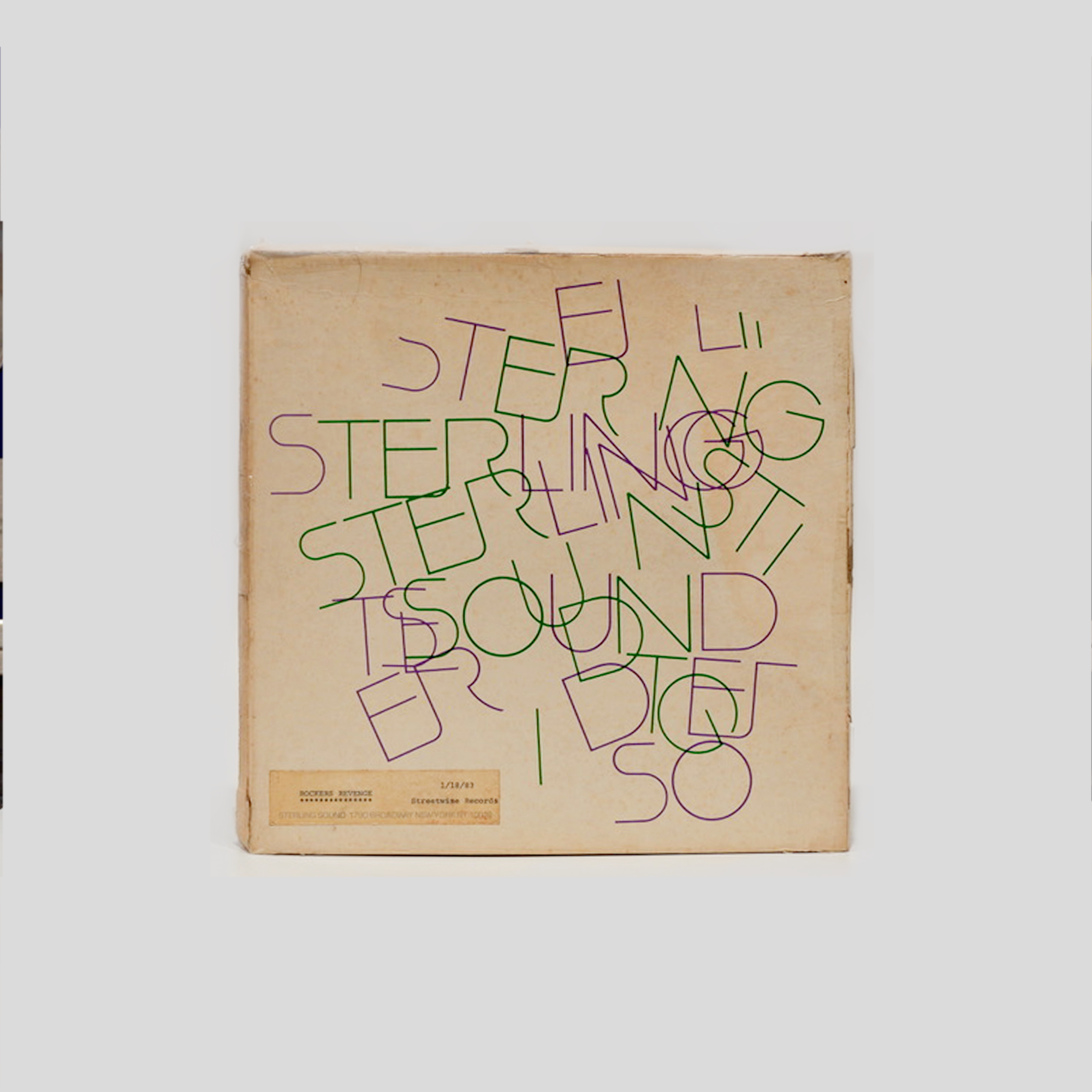

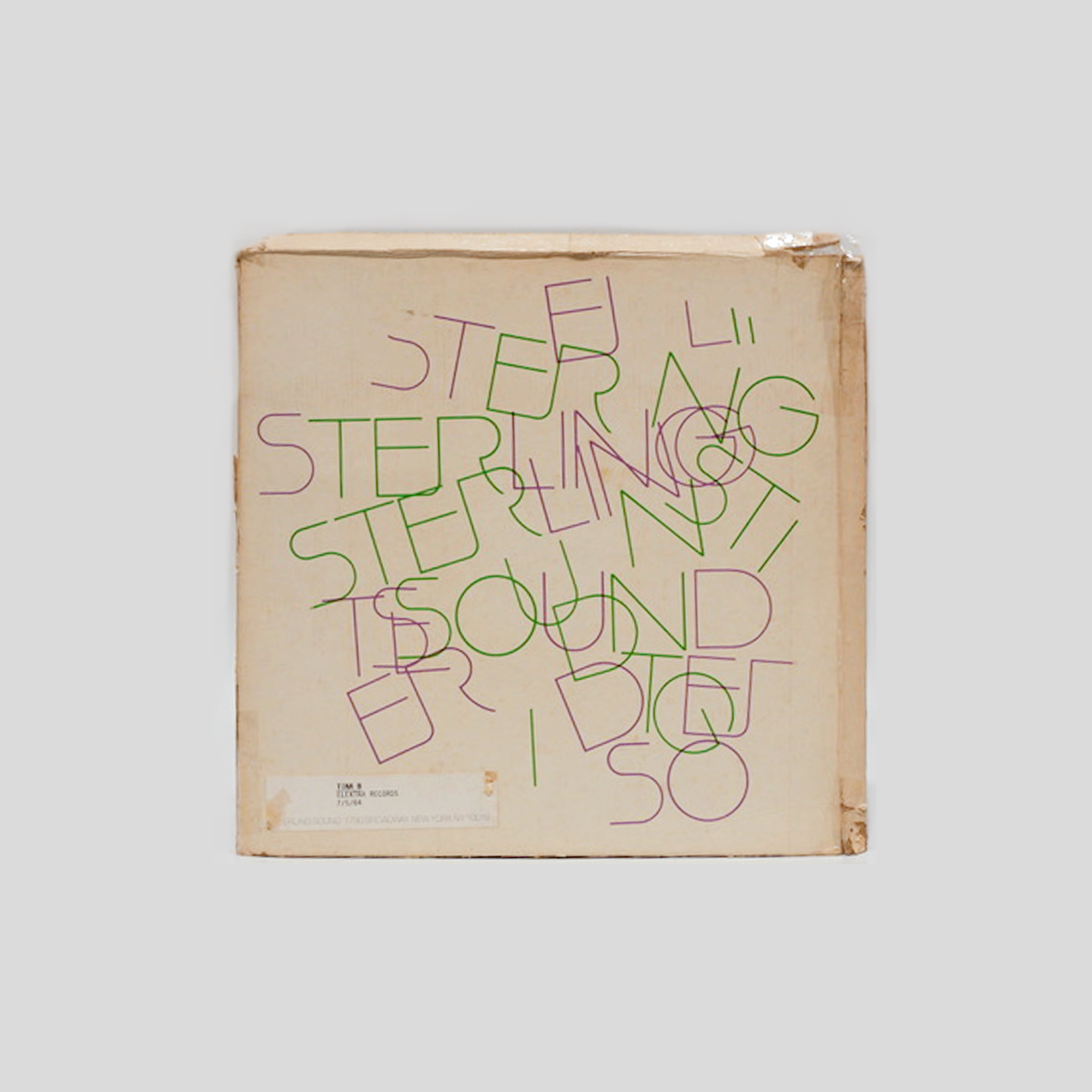

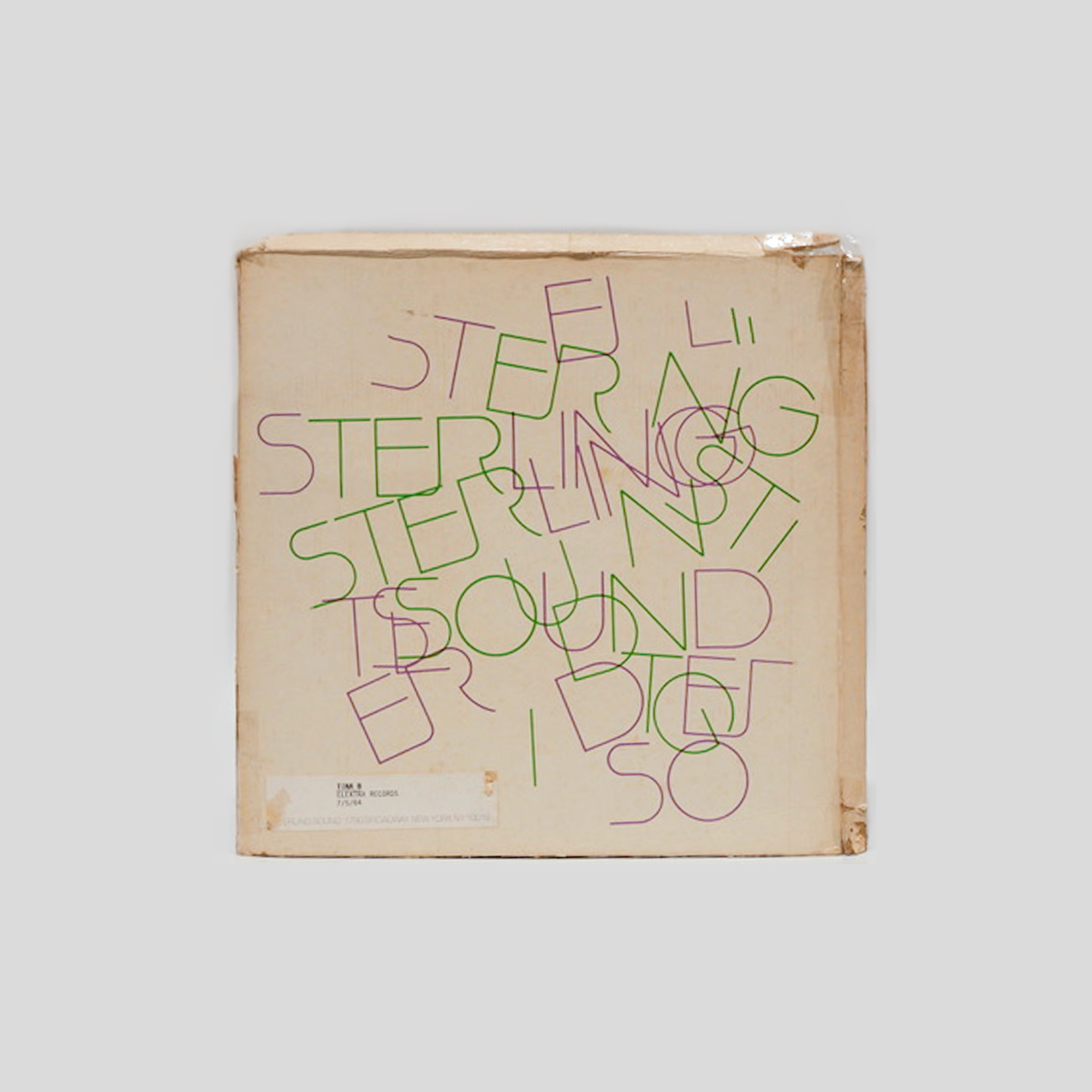

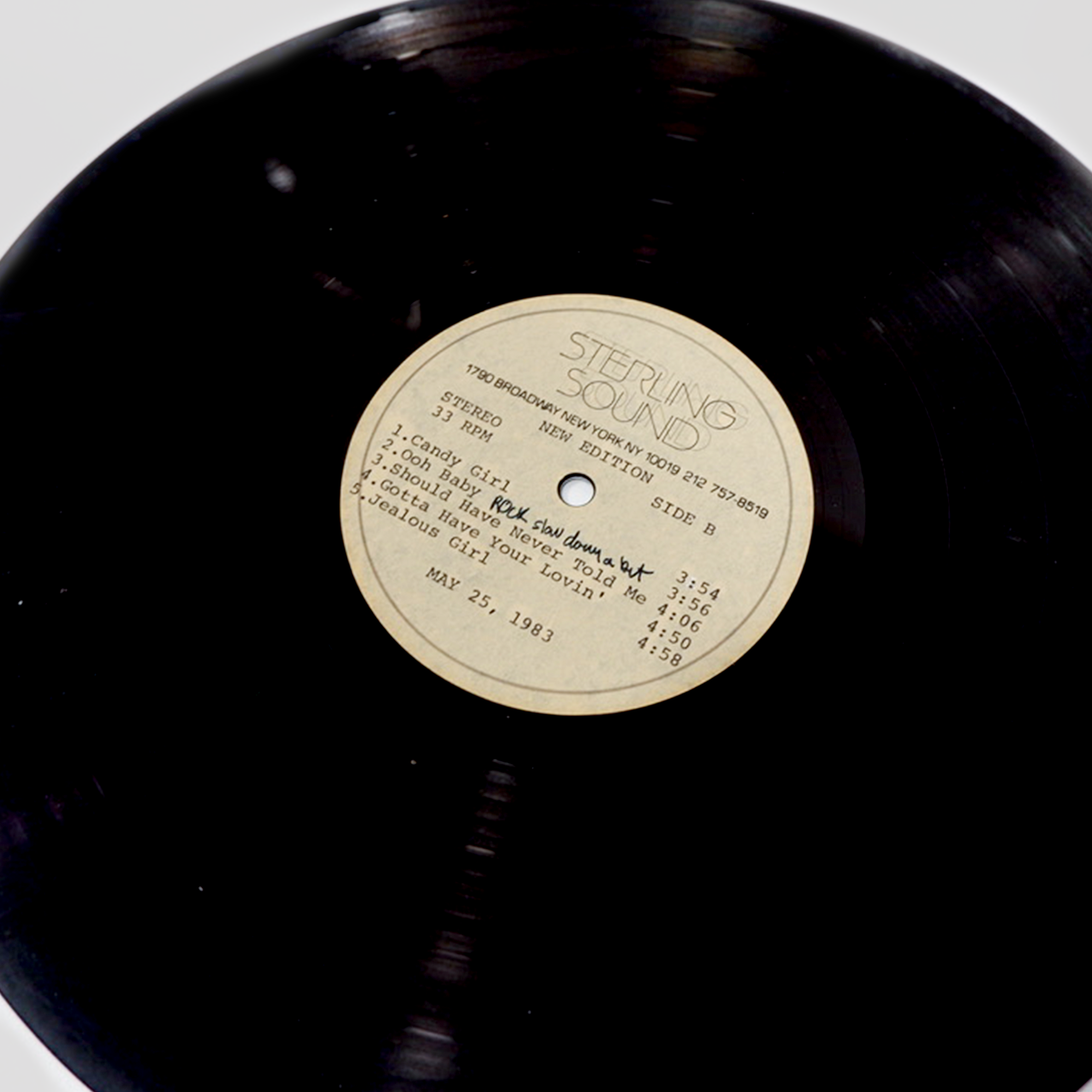

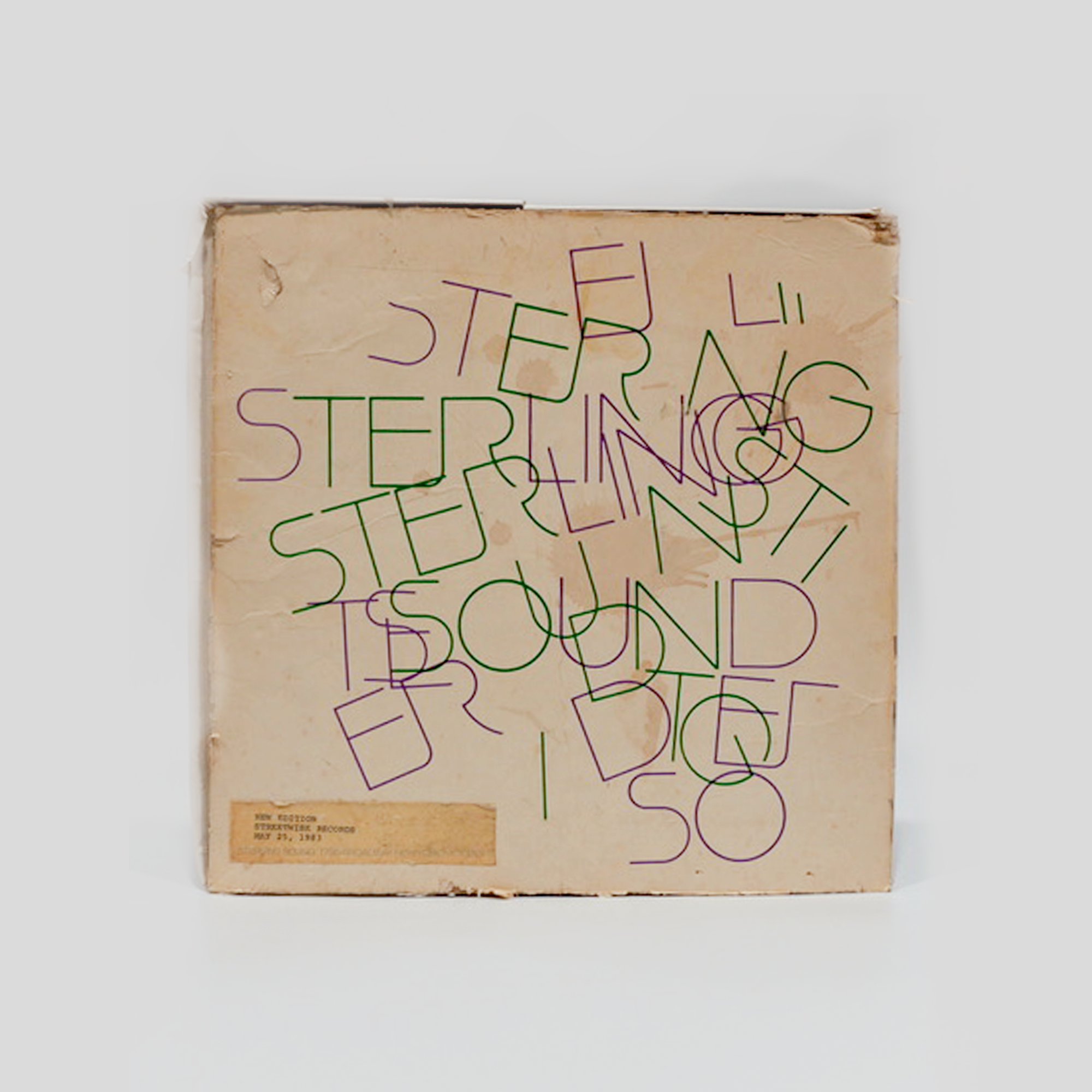

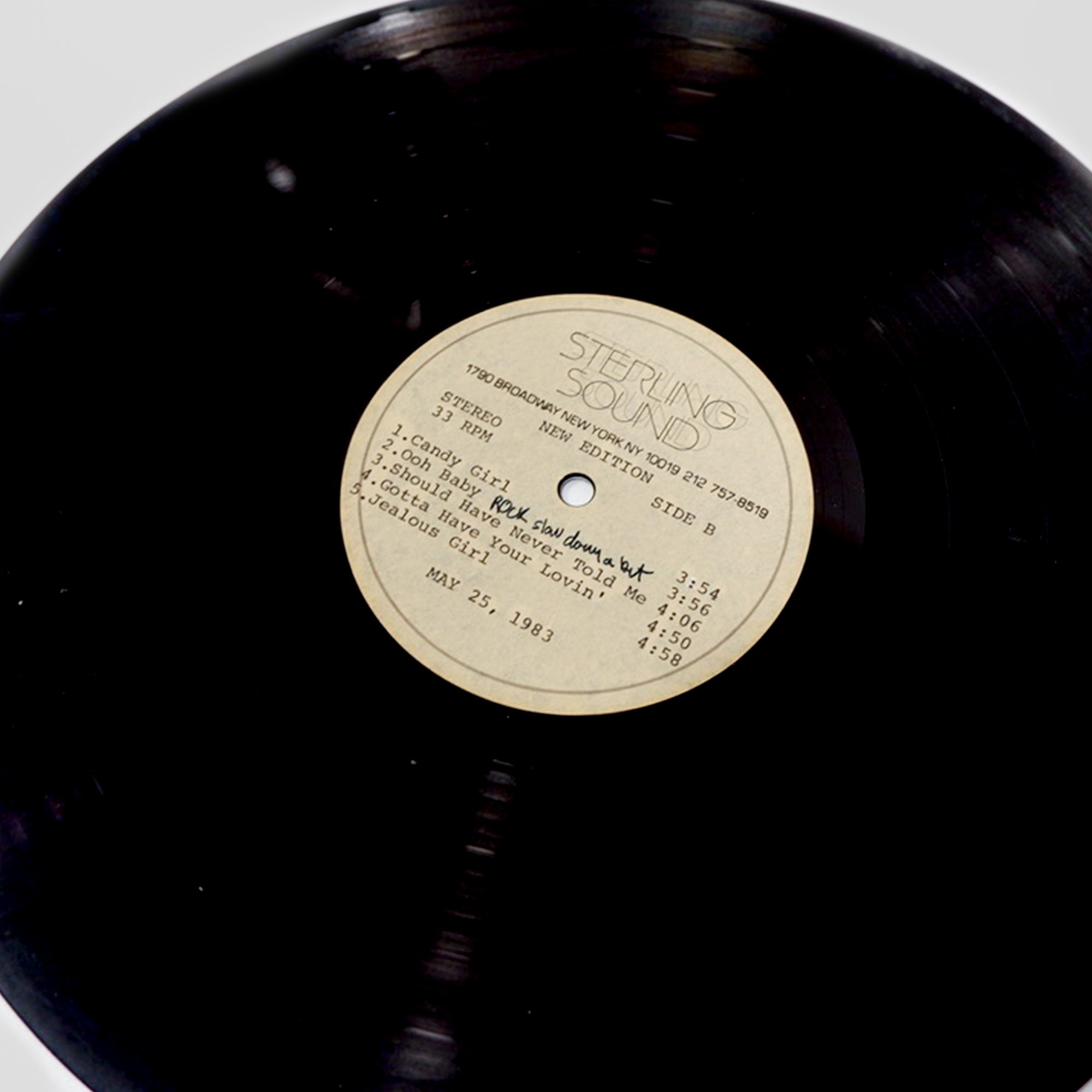

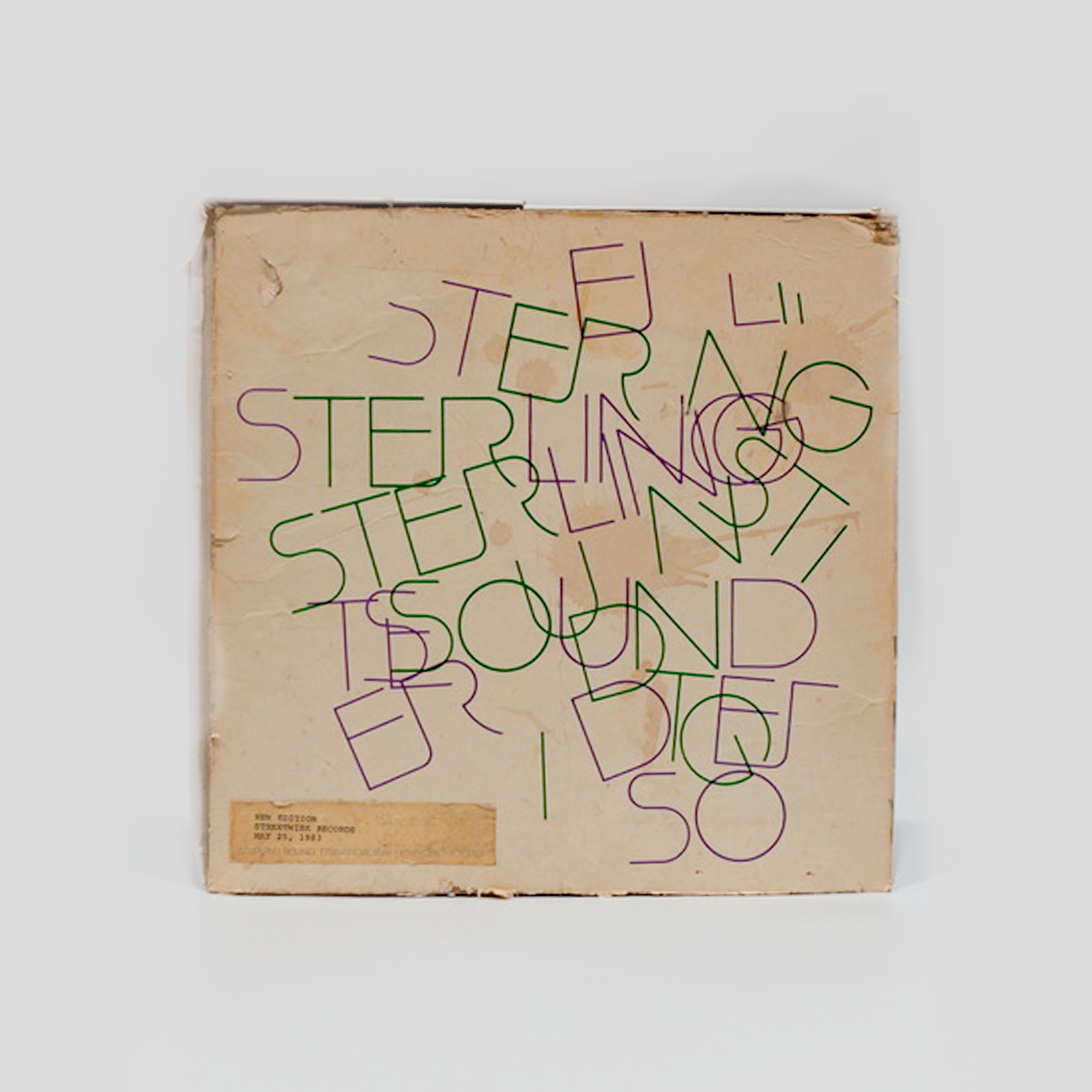

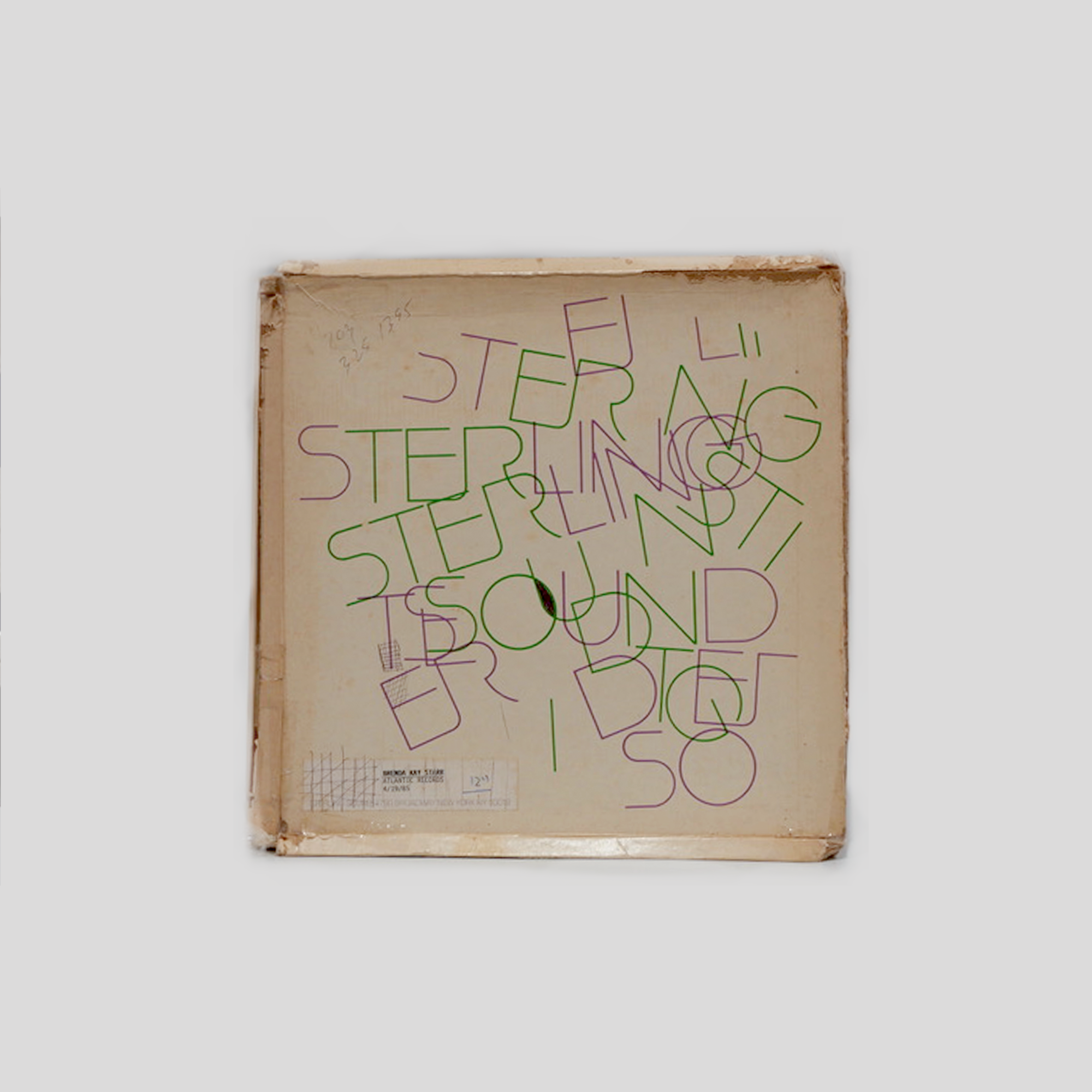

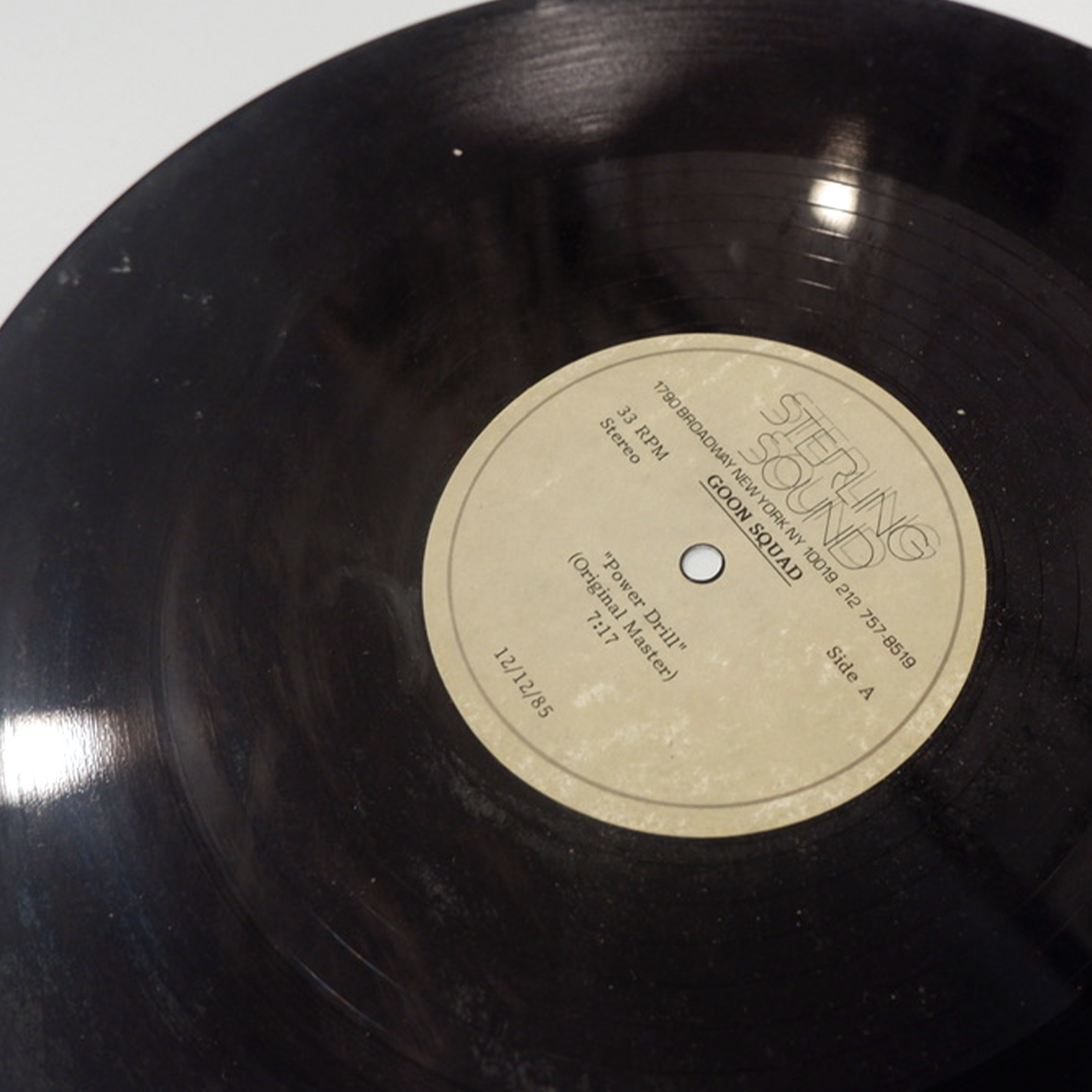

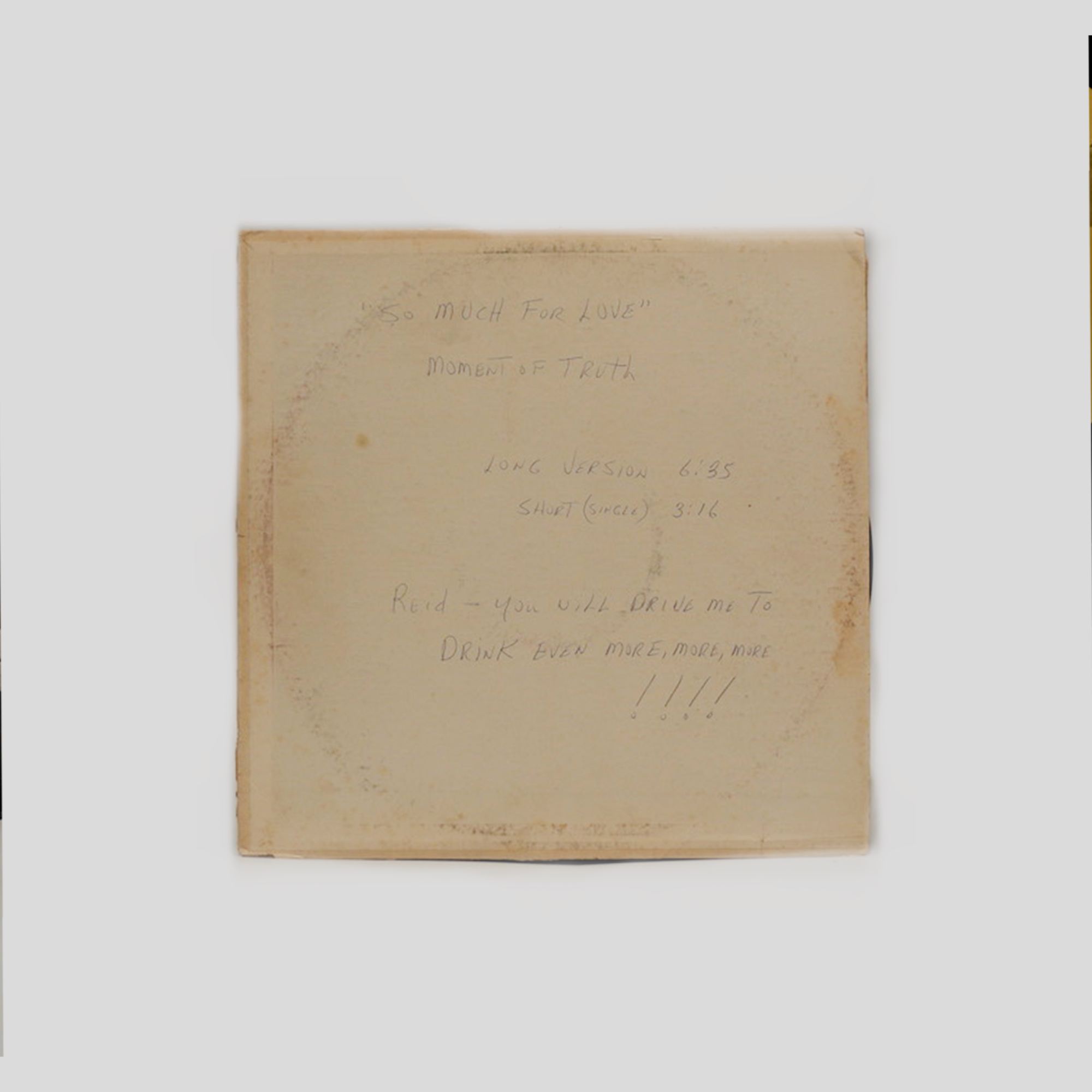

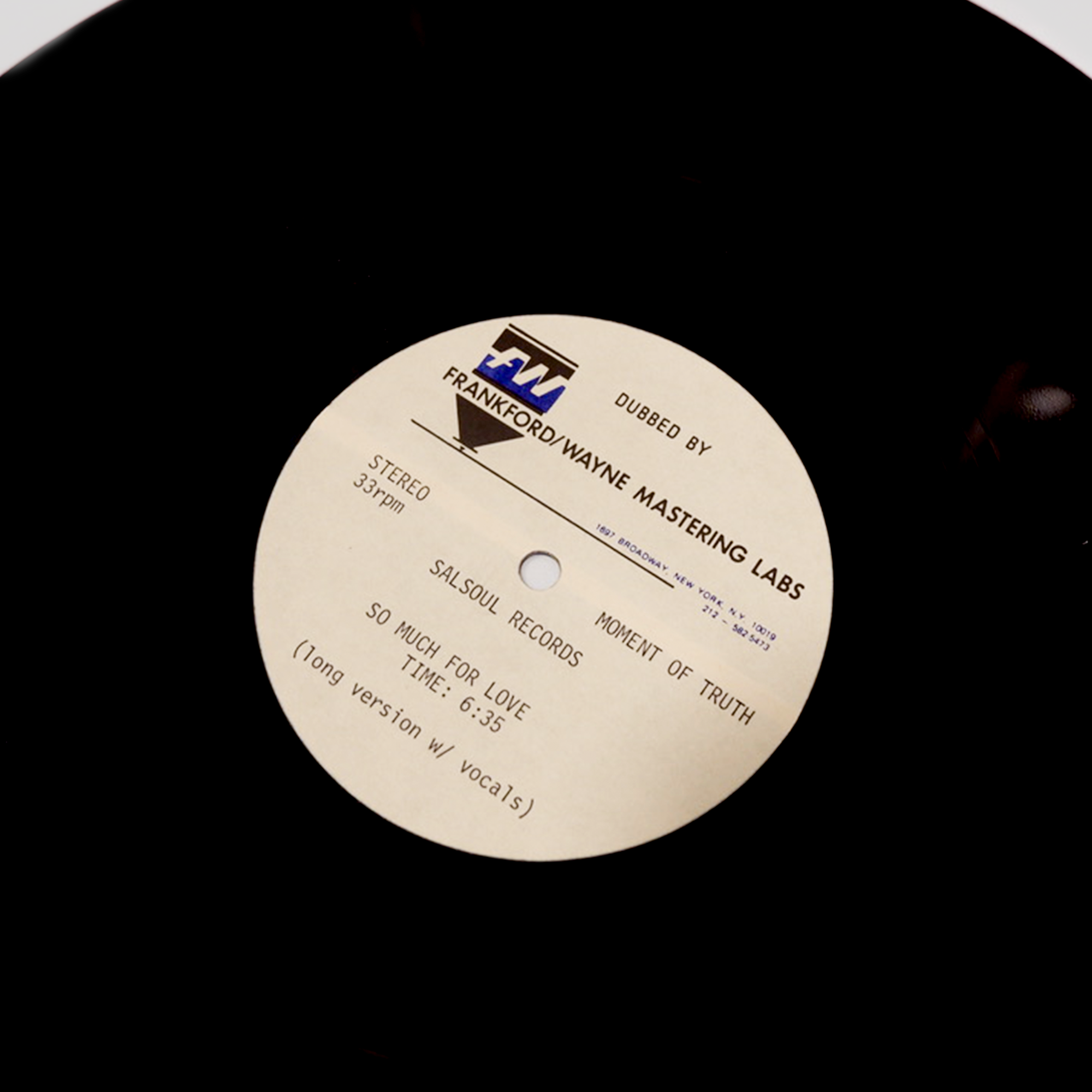

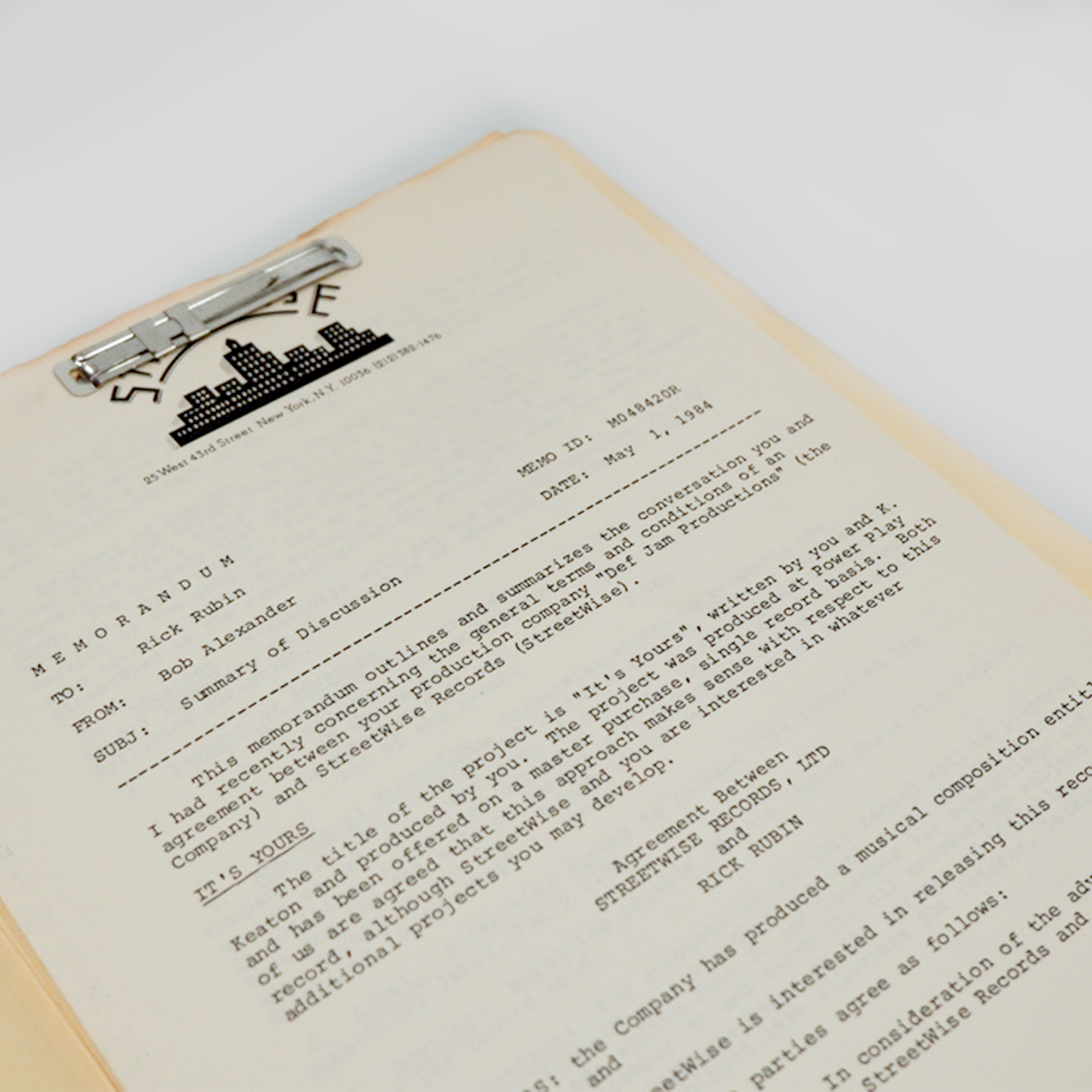

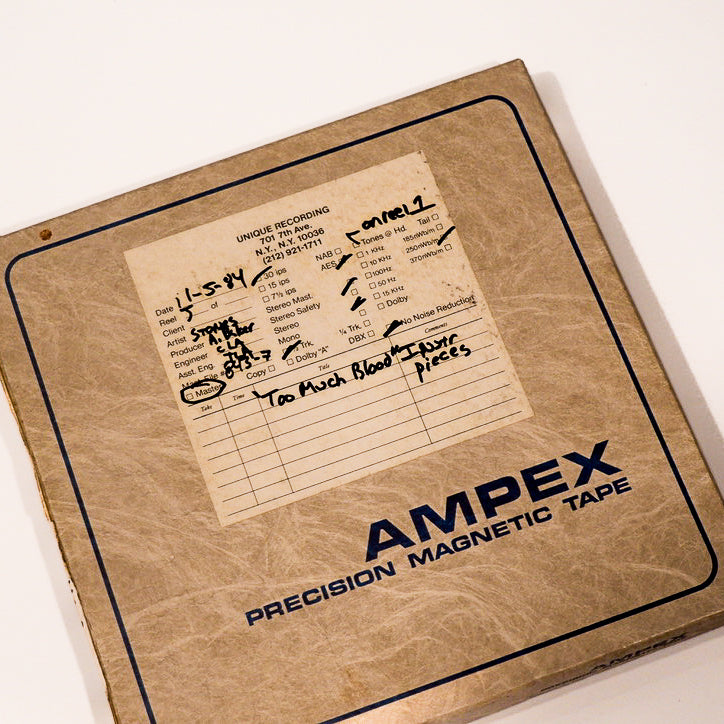

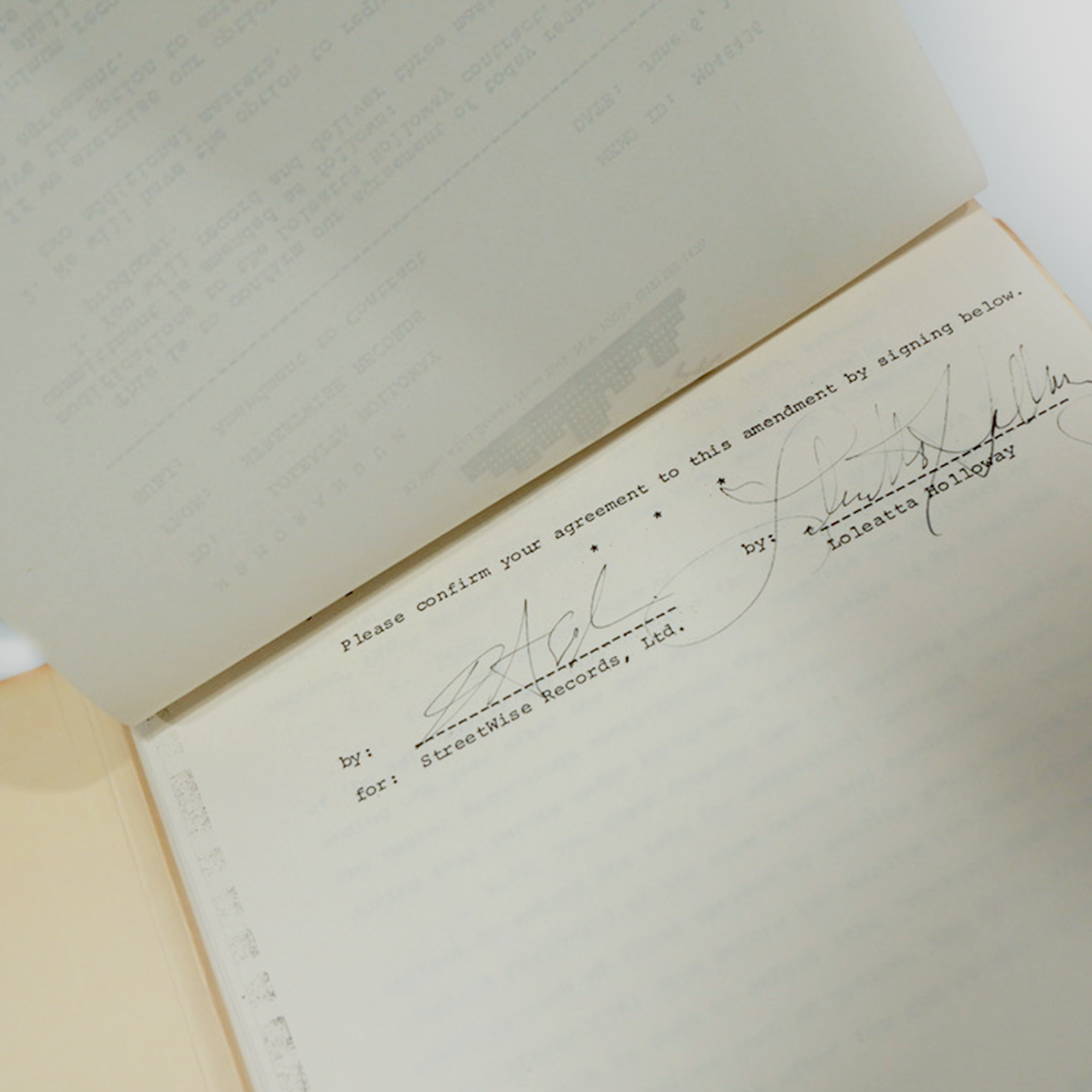

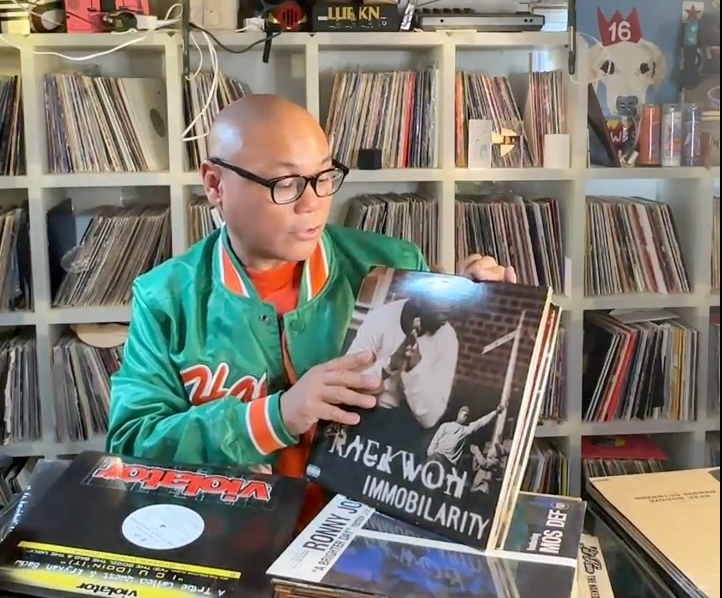

We spent a few days in Miami with him curating his Collection, uncovering lost demos, tapes and never released records. From the original Def Jam contract signed by Rick Rubin, to studio reels from The Rolling Stones, Jeff Beck and personal invites to Mancuso's Loft.

GET EXCLUSIVE UPDATES ON THIS COLLECTION

Highlights: from the clubs of nyc, to the MIAMI studio, AND MORE...

STAY UP TO DATE WITH THIS COLLECTION

ABOUT ARTHUR BAKER

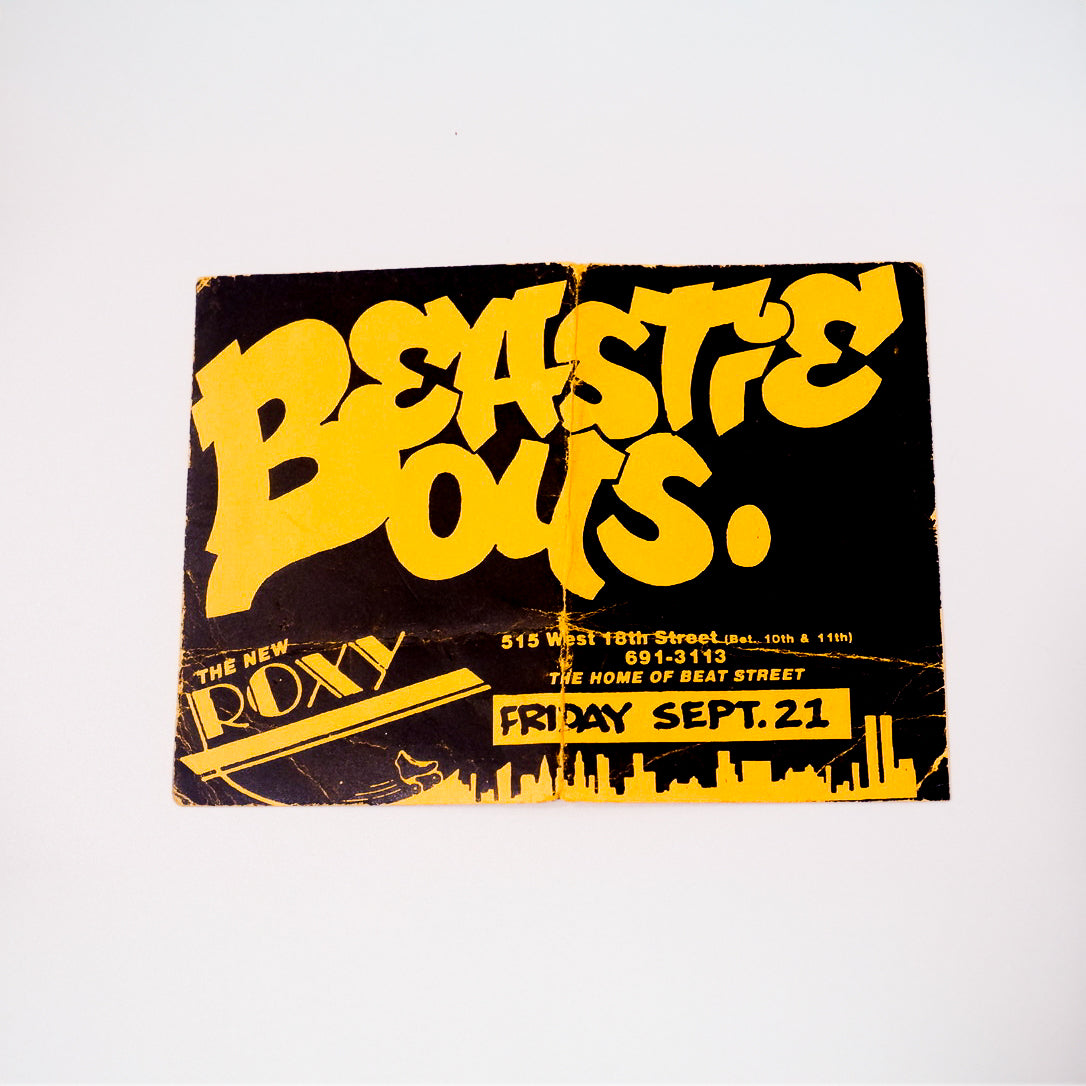

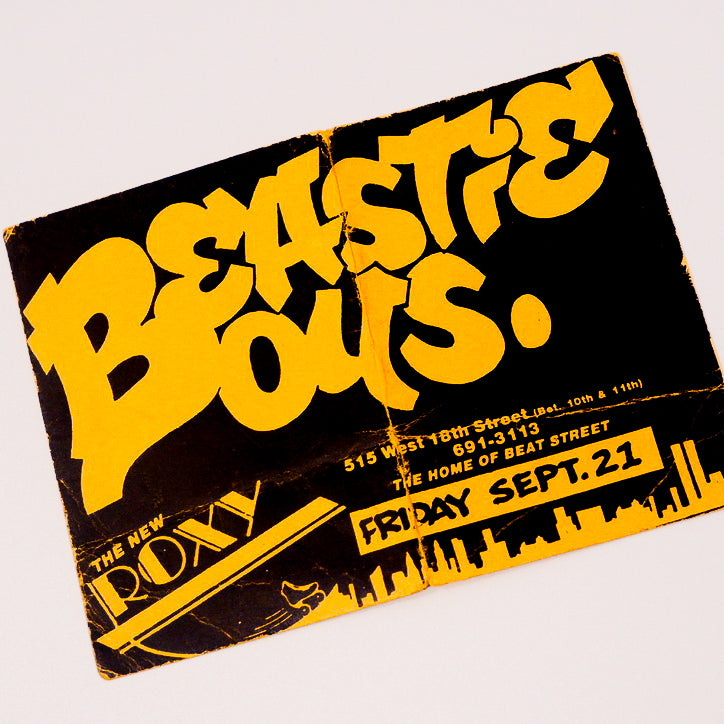

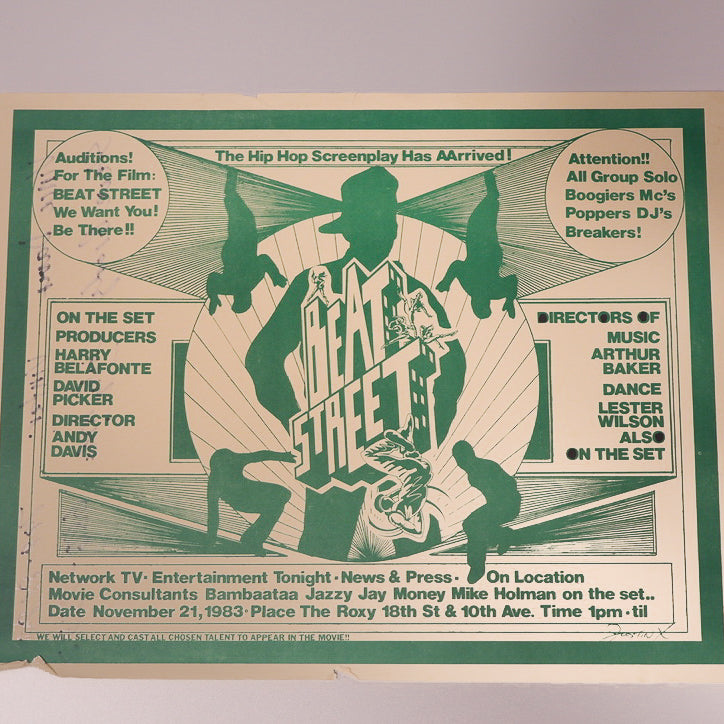

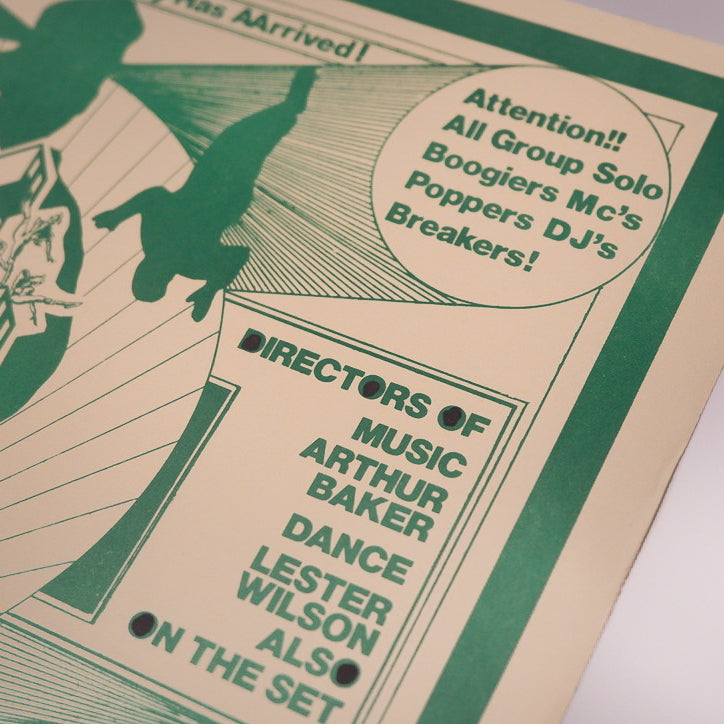

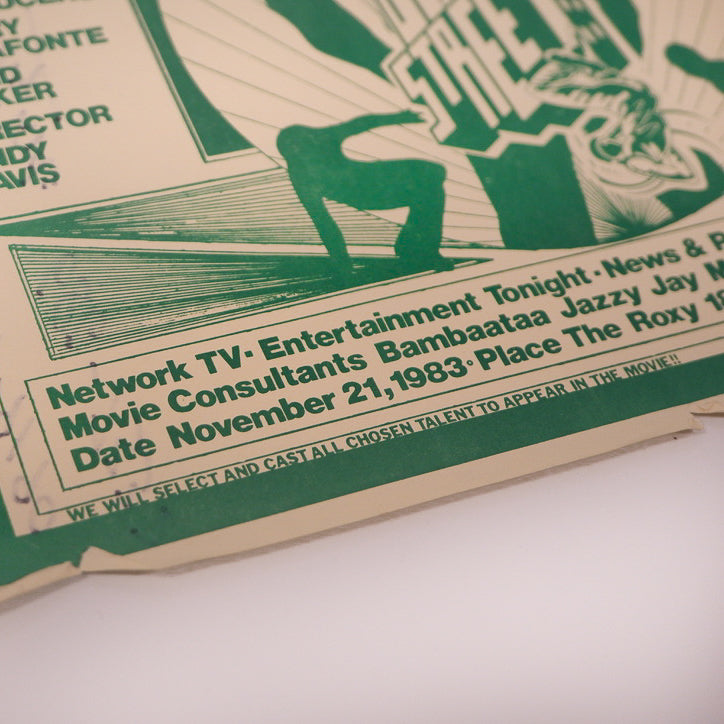

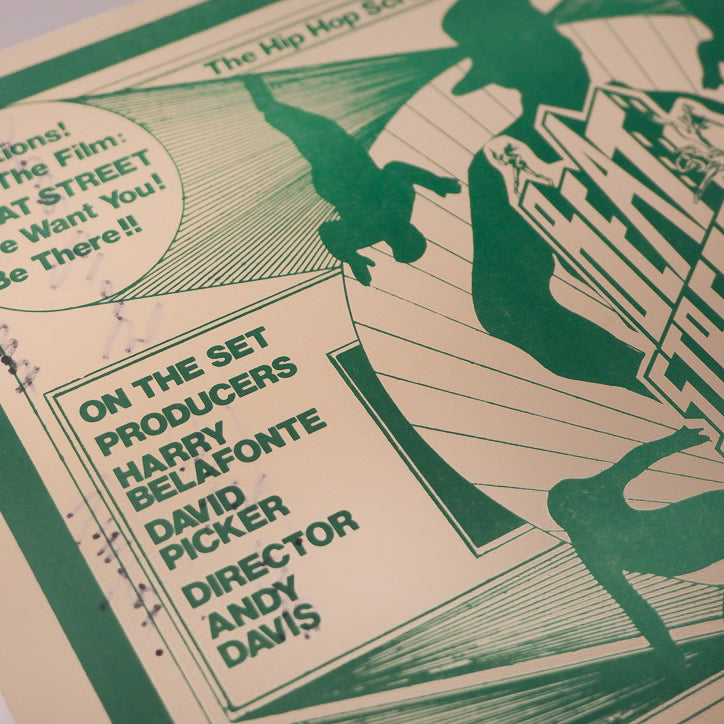

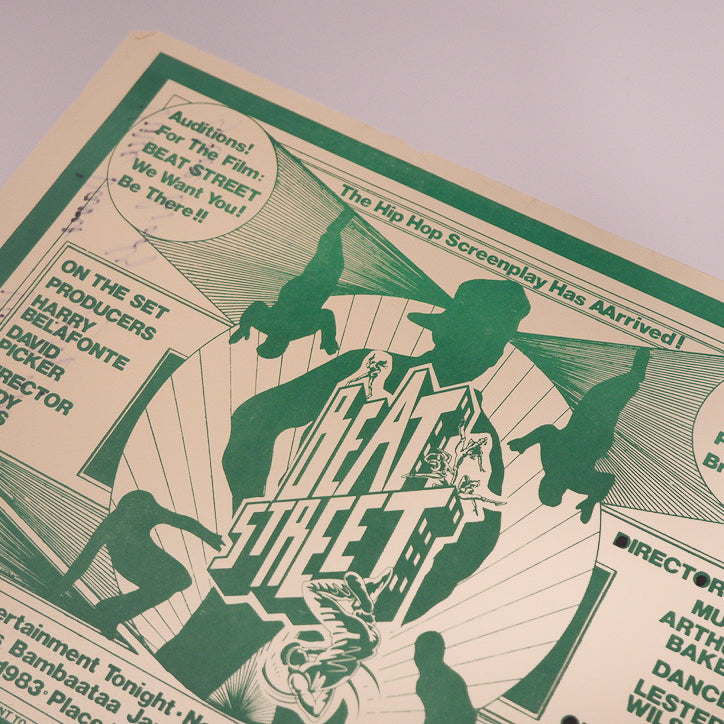

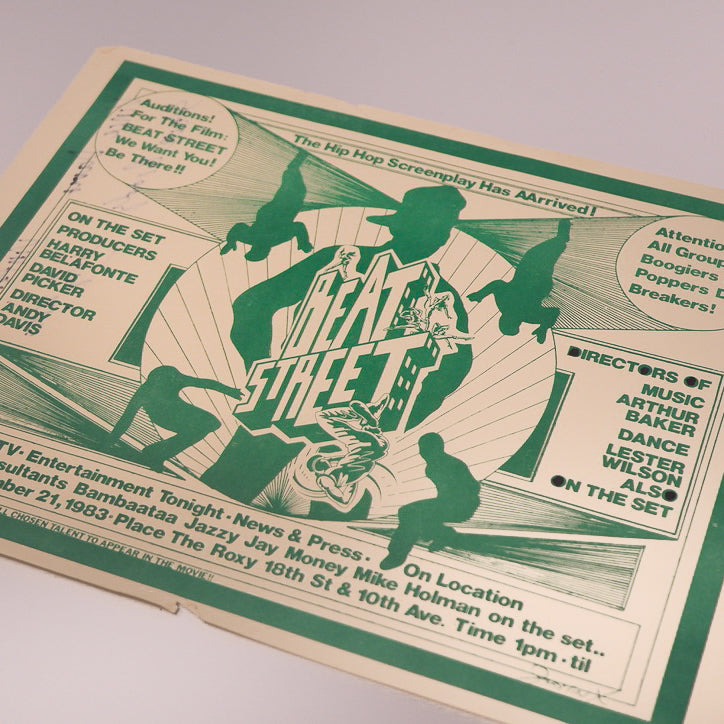

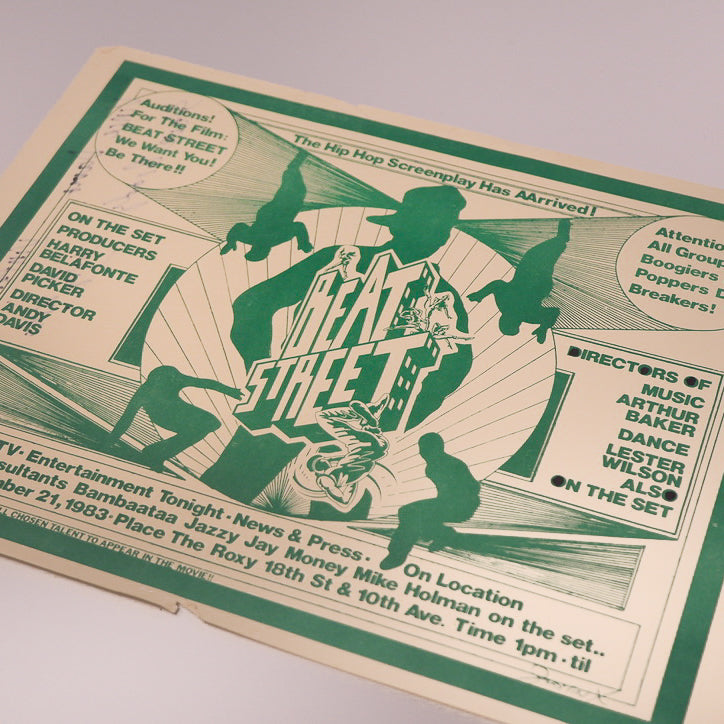

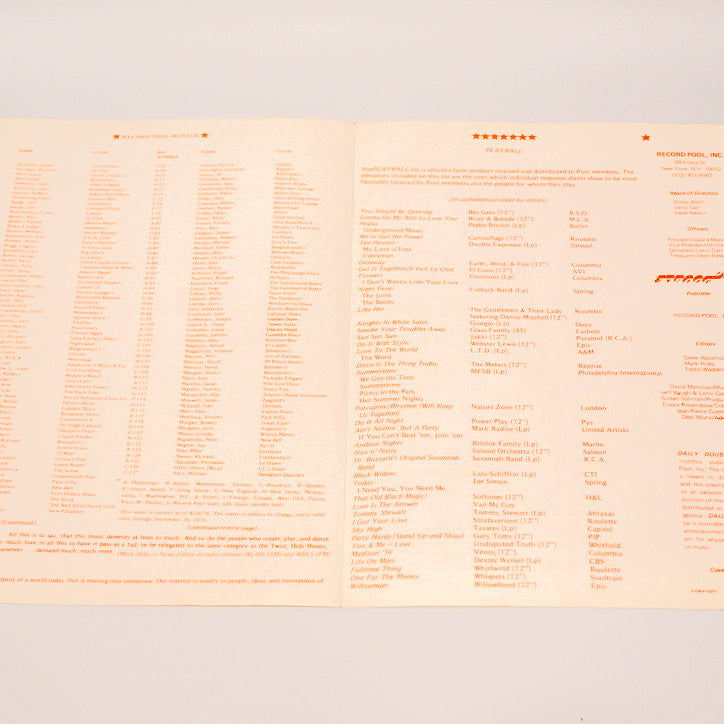

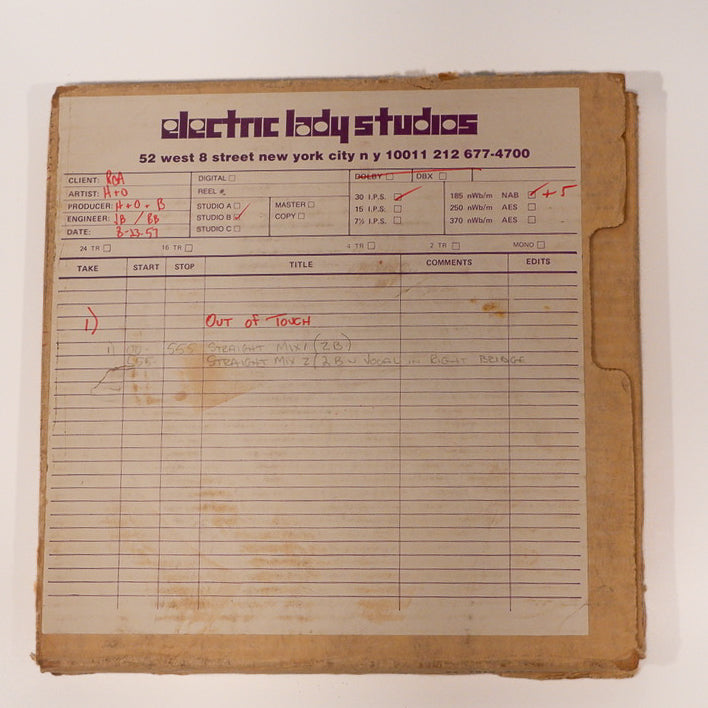

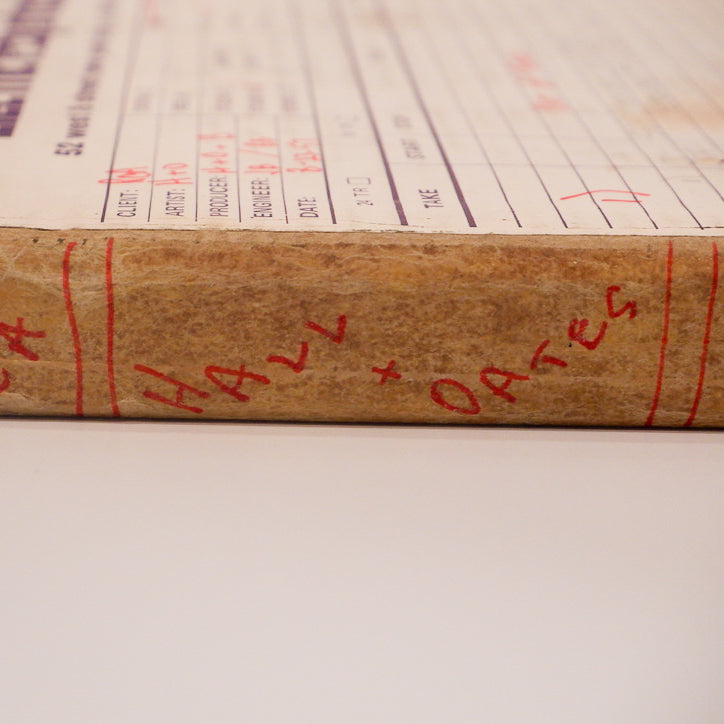

Multiple innovations by Baker arguably changed modern music. As well as pioneering the cut ‘n’ paste sampling technique, Baker also spearheaded the 12” dance music trend and popularised hiring DJs to help mix his own releases to give them a unique and genre-defying sound. Baker’s sound can be heard on tracks by legendary artists like Bruce Springsteen, Diana Ross, the Rolling Stones, Al Green, Beastie Boys, Quincy Jones, New Edition, Hall & Oates, Neneh Cherry, Mogwai, Fleetwood Mac and remixed for such films as Beat Street and Fried Green Tomatoes.

Lost chapter

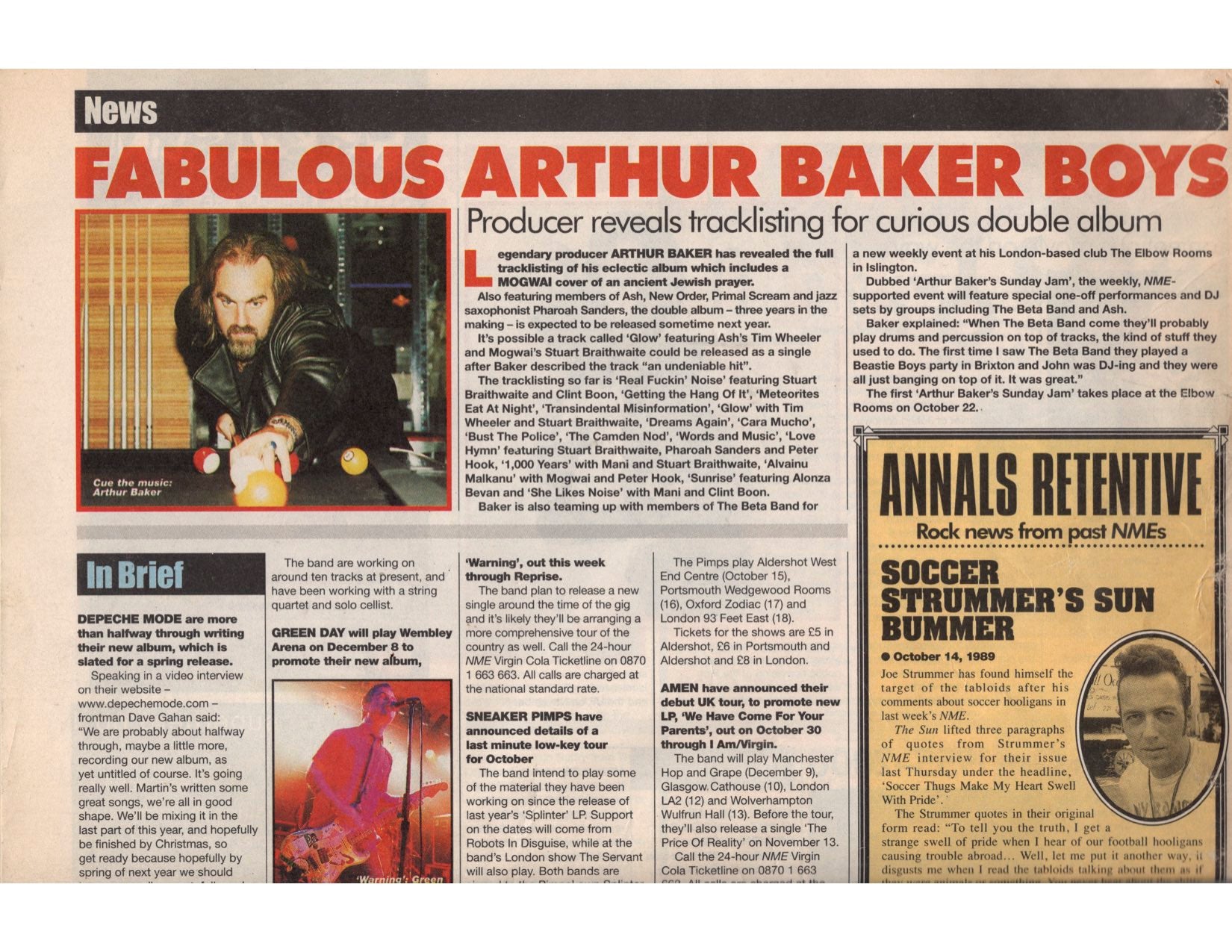

A godfather of electro and one of the most influential music producers of the 1980s, Arthur Baker rounded up an eclectic set of collaborators after decamping to England in the 1990s. Decades later, his Lost London Album is finally coming to light.

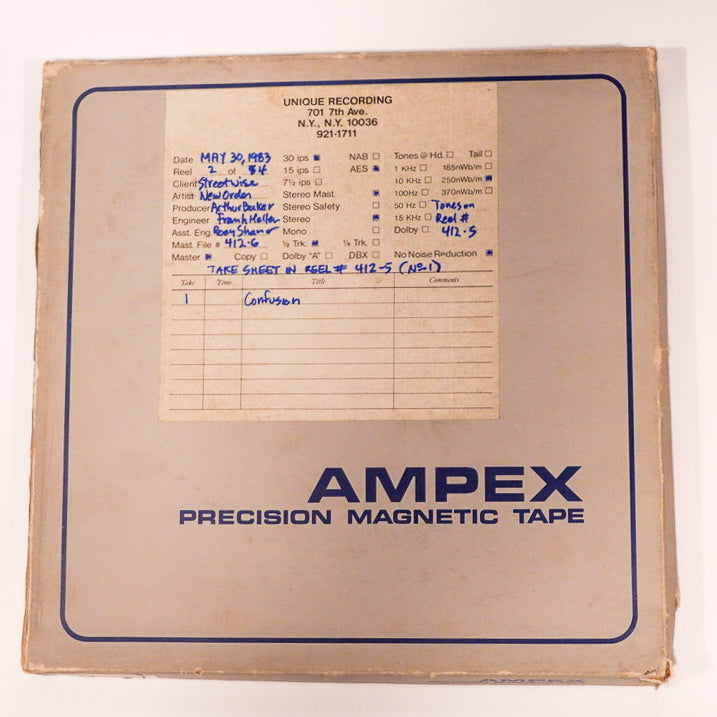

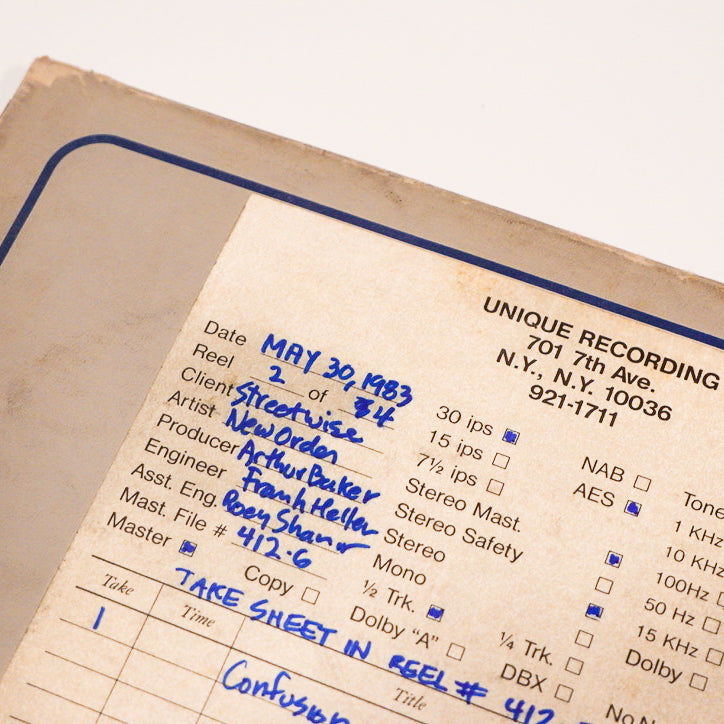

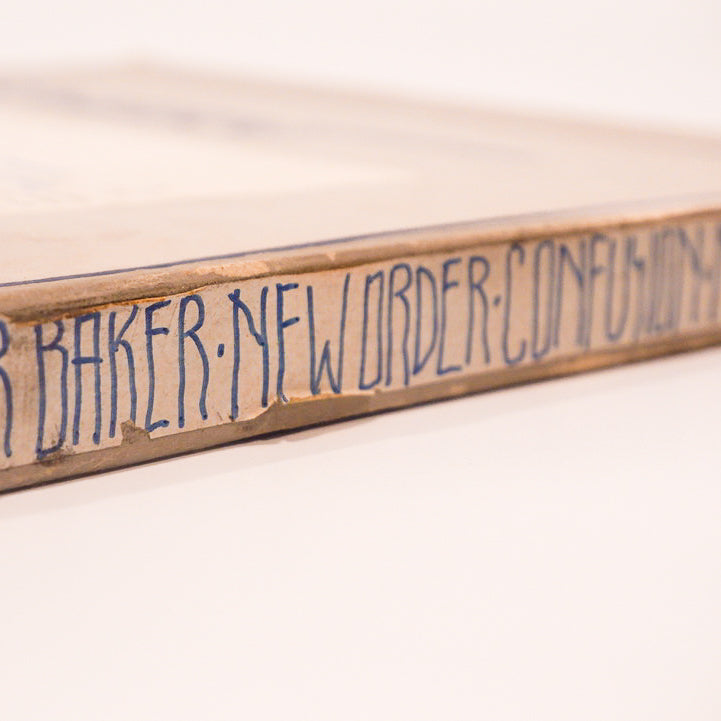

In the late ’90s, Arthur Baker was approached by Bernard Sumner of New Order—with whom he’d first collaborated on 1983’s “Confusion”—and Johnny Marr of the Smiths to produce their third album as Electronic. Among those contributing to the sessions for what would become 1999’s Twisted Tenderness was a young Kieren Hebden, who had recently completed his first album as Four Tet.

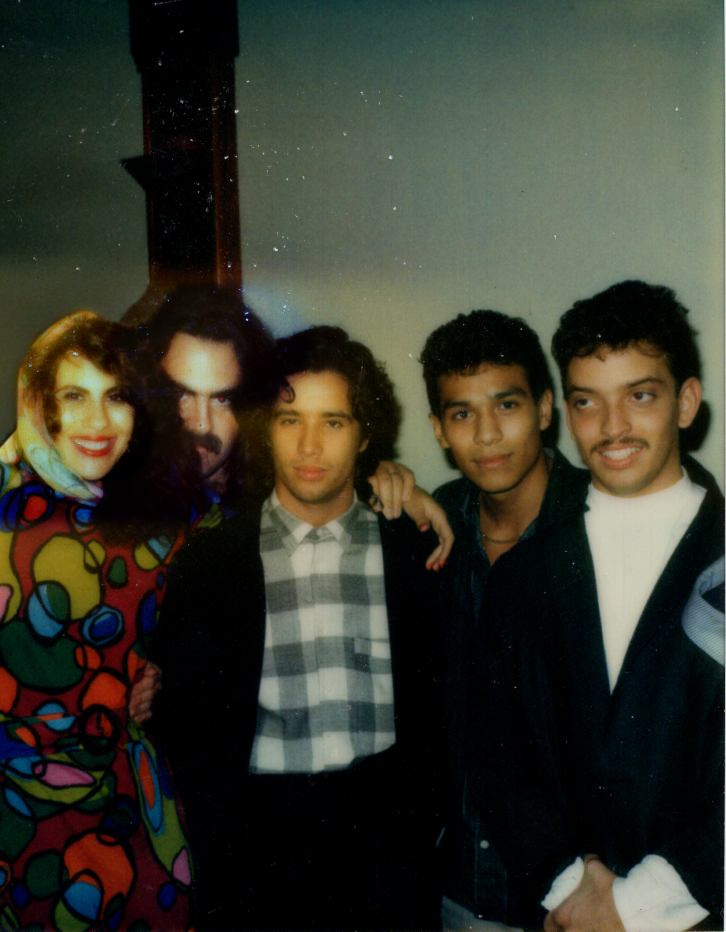

As it happened, Baker, who’d moved from New York to London several years earlier, in part to open a group of American-style pool bars called the Elbow Room, was beginning work on an album of his own as well. Hebden, along with his band Fridge, would be among the musicians and collaborators Baker would invite to sessions at London’s Mayfair Studios and Coach House in Bristol. A short list of the others includes spiritual jazz oracle Pharoah Sanders; Peter Hook of New Order; Rob Merrill and Si John of Reprazent; the Scottish band Mogwai; bassist Gary “Mani” Mounfield of Stone Roses and Primal Scream; Sabres of Paradise’s Jagz Kooner; Suicide’s Alan Vega; and the late singer Denise Johnson. The recordings, which continued on well into the Aughts, were shelved, but more than twenty-five years after commencing the project, Baker has returned to these sessions to complete what he has now titled The Lost London Album.

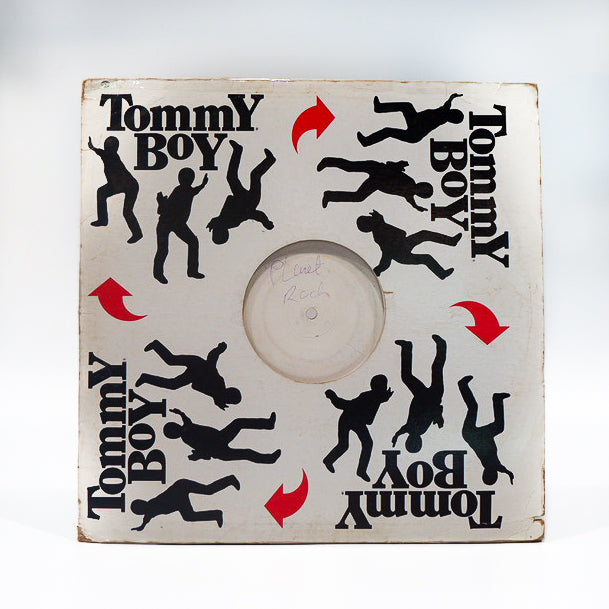

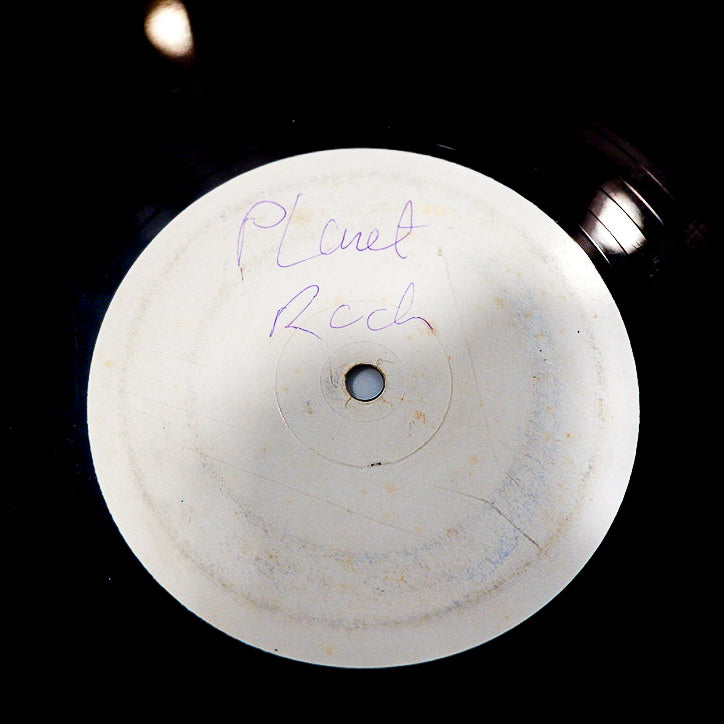

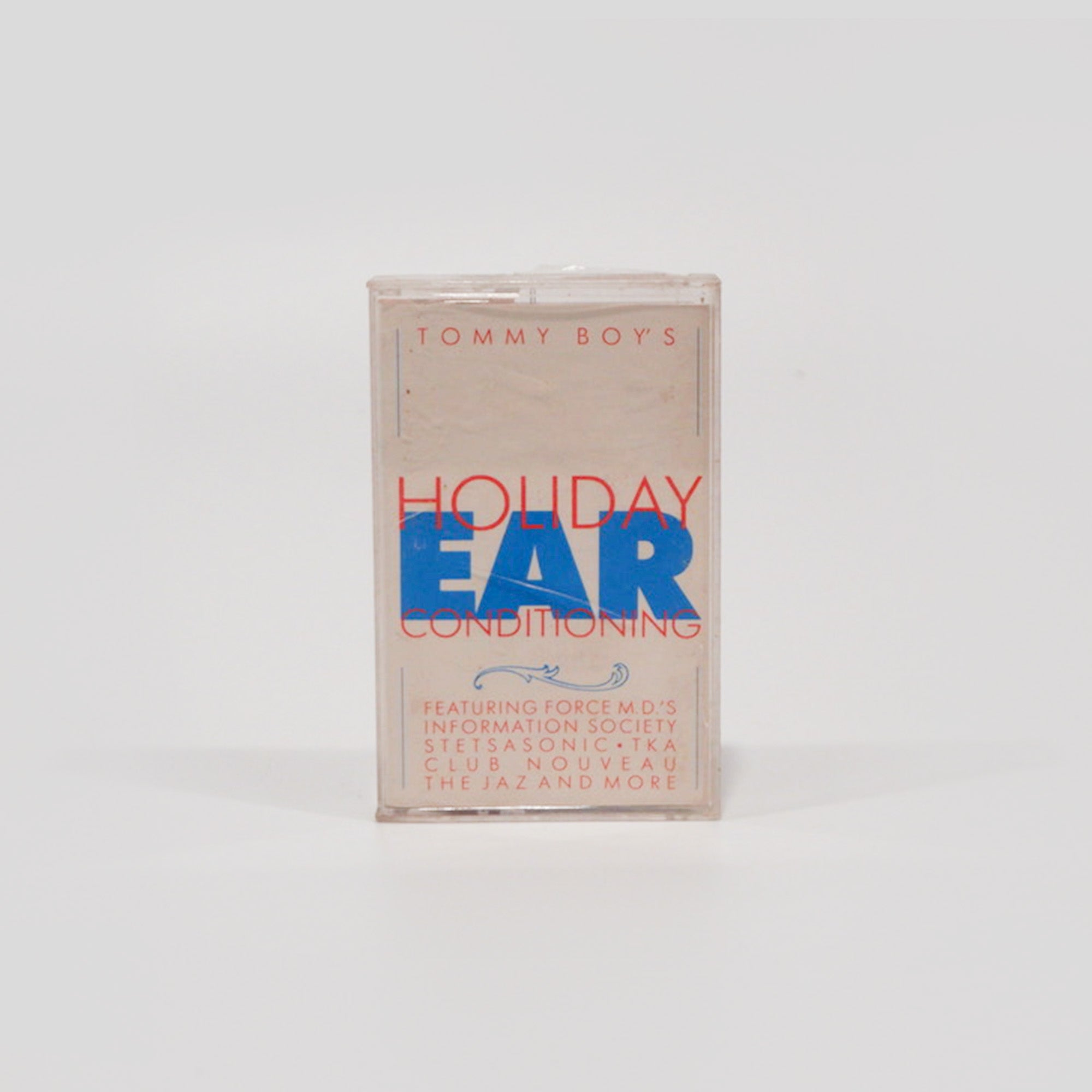

Such a union of musicians might seem incongruous, but Arthur Baker has always reveled in experimentation, pushing himself and others into unfamiliar territory. Alongside his seminal electro productions for Tommy Boy Records and his own Streetwise label, including Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force’s era-defining “Planet Rock” and “Walking on Sunshine” by Rockers Revenge, and his influential collaborations with Freeez (“I.O.U.”) and New Order (the aforementioned “Confusion”), were genre-jumping projects for the likes of Dr. John, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Hall and Oates, and even the Rolling Stones.

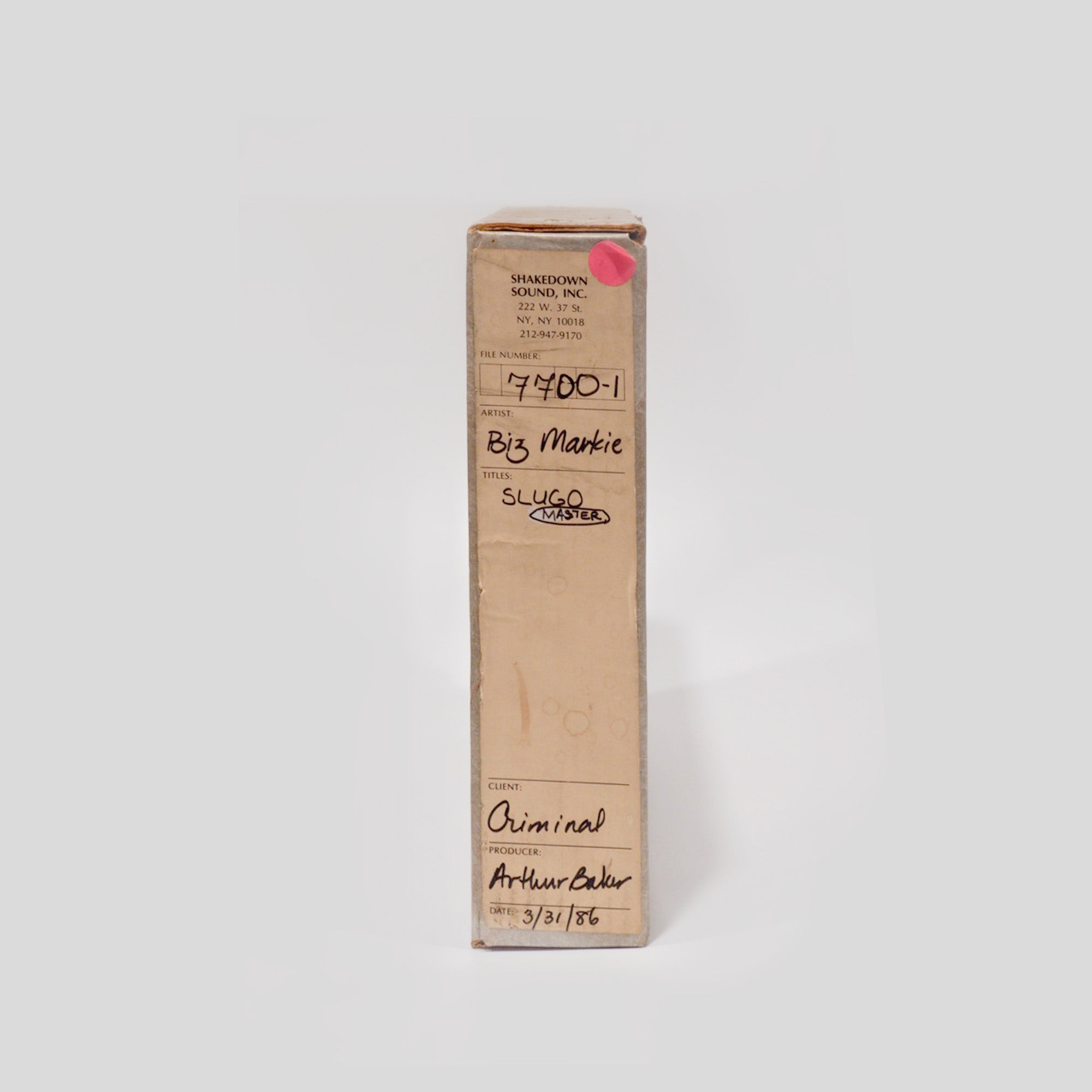

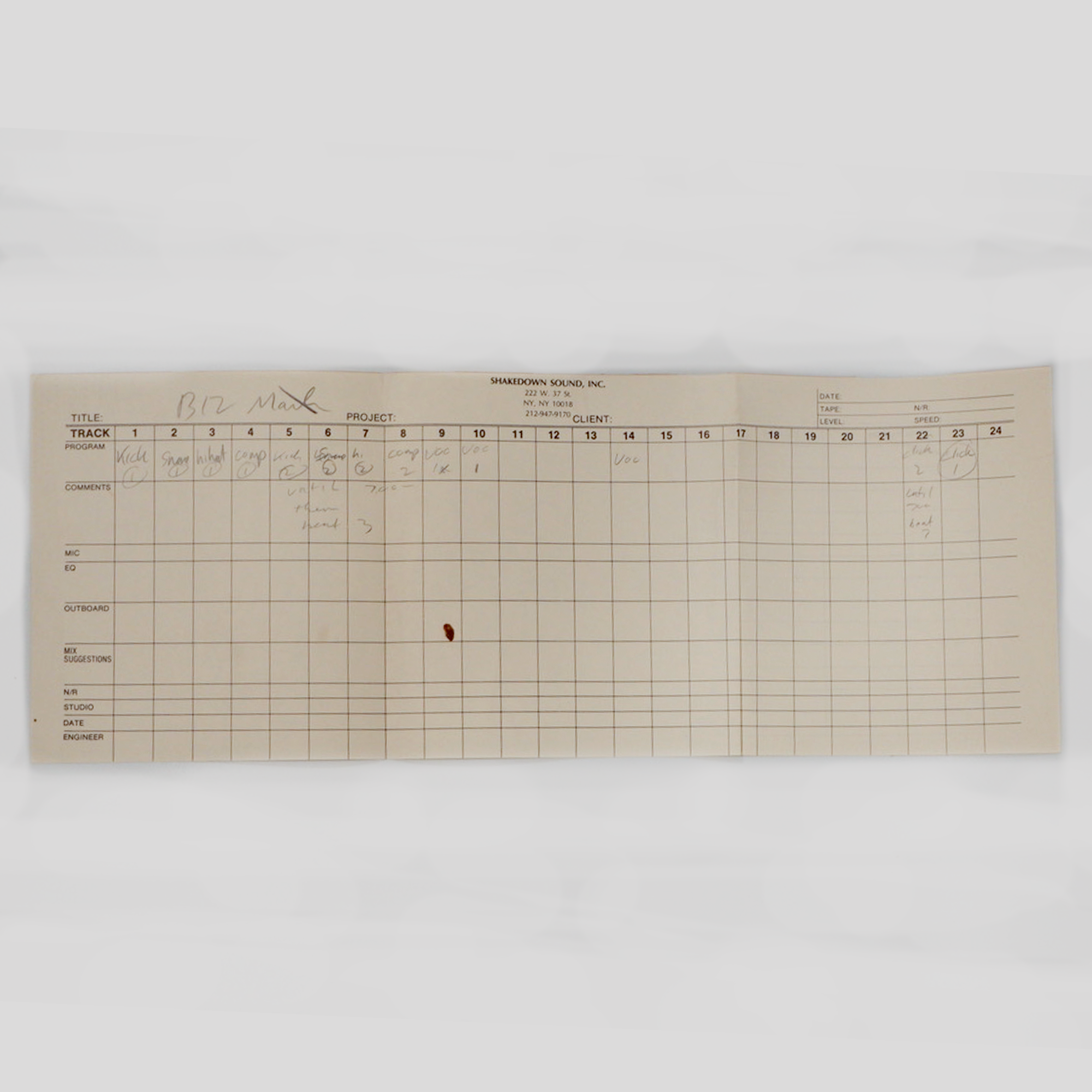

By the mid ’80s, Baker, working from his own Shakedown Sound Studios in New York, had become the producer of choice for legacy artists looking to move in new, electronic directions. But the Boston native, having been deeply immersed in the club scene of the ’70s and ’80s, also clung resolutely to his underground roots, founding Criminal Records as a home for early house music and other underground dance sounds in 1986. Having never lost his itch for both innovation and collaboration, he has kept an ear towards emerging artists and sounds through to today.

With the now Miami-based Baker set to release his Lost London Album this year via New State Music, alongside an autobiography, Looking for the Perfect Beat (Faber & Faber), we connected with the legendary producer, songwriter, DJ, and creative instigator to discuss this once-missing chapter from his life story and reminisce on highlights from his ever-evolving, nearly fifty-year career.

How did the Lost London Album project come about?

Arthur Baker: I was living in Primrose Hill, where I worked from Mayfair Studios. It was by Creation Records and also near the studios of Primal Scream. It was a really cool environment with Neneh Cherry and [producer] Cameron McVey living right opposite me. That became my hood for a while and I started meeting all these musicians. At the time, I had a girlfriend who was really into indie stuff and introduced me to groups like Mogwai. It was a magical time for me with music and meeting all these great people.

The track you wrote and arranged for Mogwai used the Jewish hymn “Avinu Malkeinu.” Where did that idea come from?

As a child, that hymn was the first music I ever heard in the temple at Yom Kippur, and I had always loved its beautiful melody. The song always resonated with me. When I heard Mogwai, I thought this would be an amazing track for them to handle. So I made them a demo just playing it on my bass and they loved the concept. [After recording the version which appears on The Lost London Album] they then went off and took the track to another level [as 2001’s “My Father My King” with producer Steve Albini].

Like what you're reading? Get our summer 2025 COLLECTORS issue featuring this story on ARTHUR BAKER

Pharoah Sanders, Peter Hook, Stuart Braithwaite, and Kieren Hebden aren’t musicians you would associate with each other.

I guess you might naturally put Kieren in that jazz environment but I can’t imagine you would find Hooky listening to Pharaoh Sanders. But I have always loved doing collaborations like this, and just going with my own tastes and with what I think might work.

What are your memories of the Pharoah session?

We went into Mayfair, which was like my home studio at the time, with Pharoah and did multiple takes of both “Love Hymn” [also featuring Kieren Hebden, Stuart Braithwaite, and Peter Hook with keyboardist Merv de Peyer] and “Spirituality.” I then got him to do [a version of Sanders’ 1969 recording] “The Creator Has a Masterplan” with just a piano and him playing. It was all totally amazing. The deal with Pharoah was he wanted £3000…in cash.

Pharoah is one in a very long list of your collaborators. I wanted to talk about one of your earliest from back in the ’70s, and that’s disco producer John Luongo.

He was a real inspiration to me because he was doing what I wanted to do. Back in Boston, he had launched the magazine Nightfall that put on the first disco awards. He was like a mentor but I also helped him get on with his career. I produced the second remix he was involved in, the Hearts Of Stone’s “Losing You” in 1977. Then we did North End’s “Kind of Life” for West End right after he did Jackie Moore’s “This Time Baby,” which was really successful. And then he moved to New York and really took off.

You were there at the birth of disco watching the great DJs of the day. Who were the ones who most inspired you?

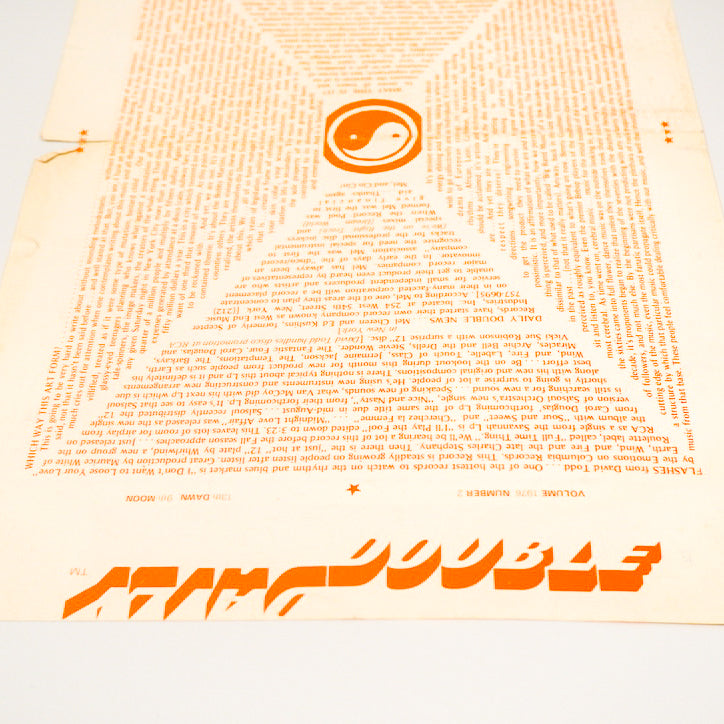

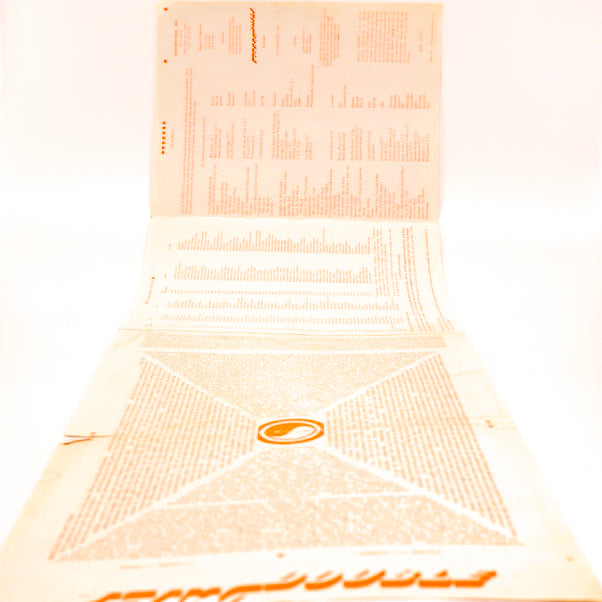

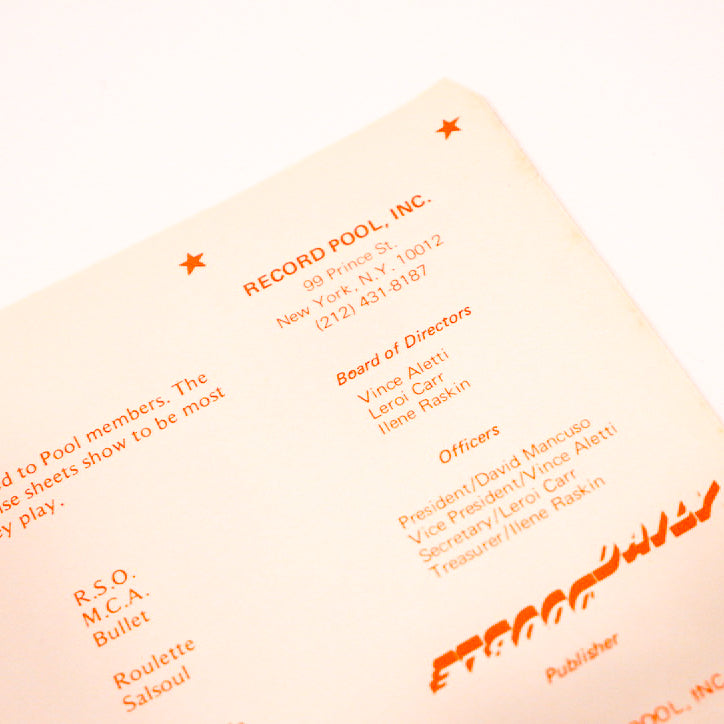

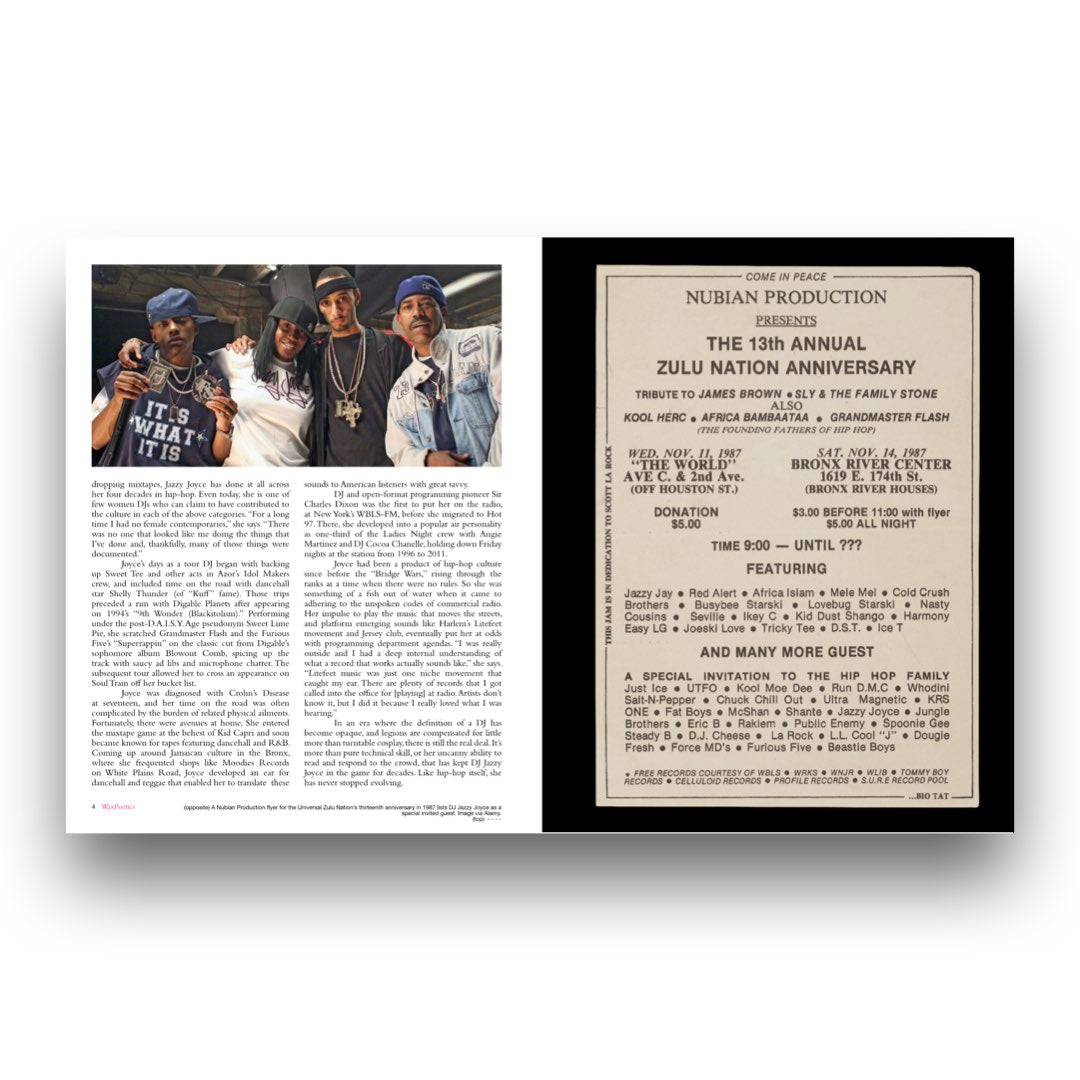

John Luongo was a great DJ, extending the breaks on records, going between two copies much like a hip-hop DJ would in the Bronx. Walter Gibbons was another really great DJ. I tell the story in the book of first hearing him play Double Exposure’s “Ten Percent.” That night at [Manhattan club] Galaxy 21, I was with David Todd, who was also one of the great DJs and mixers. I had heard the song before but, when Walter kept going back and forth in the mix, we were like, “What is this?” We thought he was mixing between two records like John Luongo but Walter told us it was his remix of “Ten Percent.” So that really was the start of all of that.

These DJs used the clubs as testing grounds for their own productions, as you would at the Fun House at the height of electro.

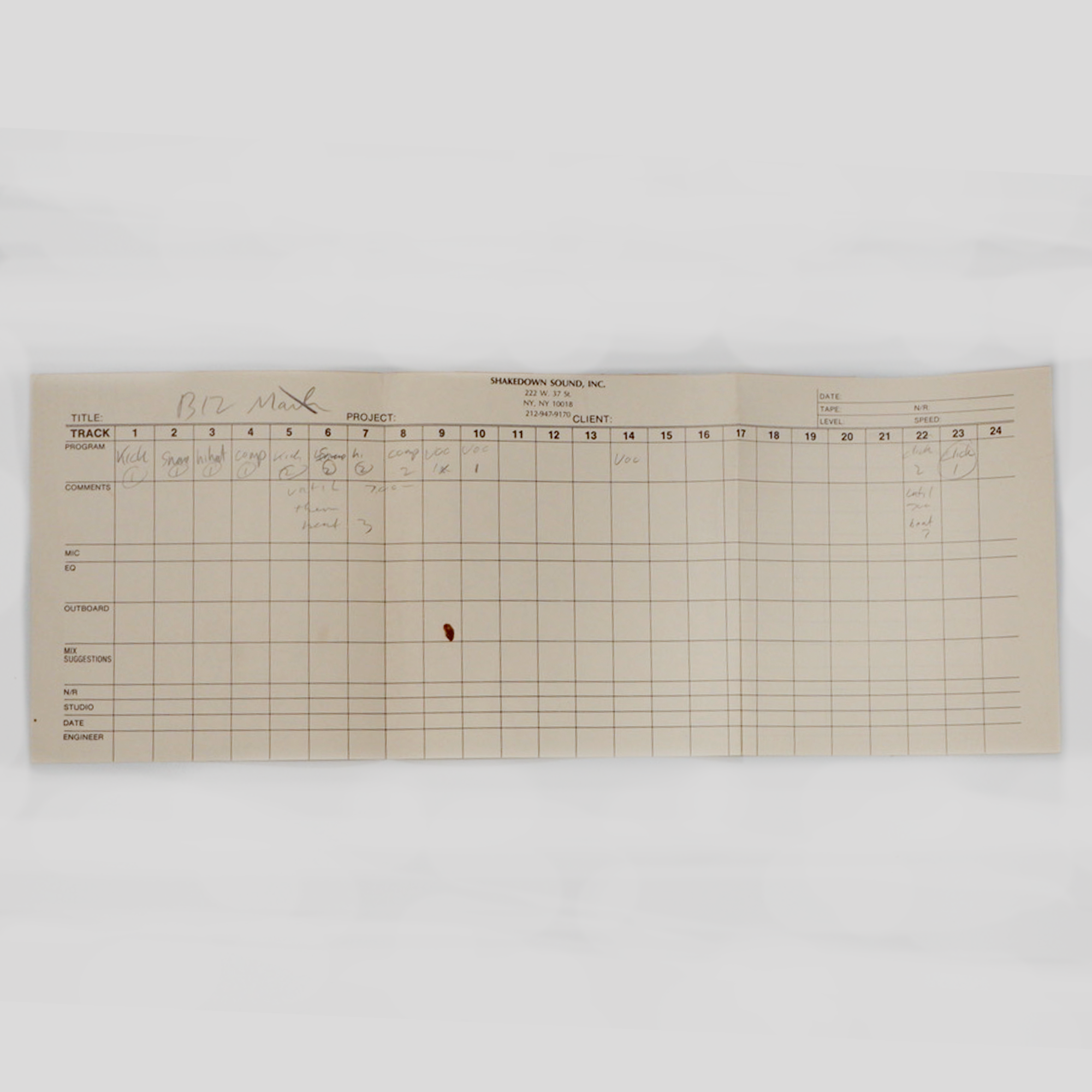

Yeah, the Fun House really was our sound stage where we would watch the reaction of the dancers. I knew the crowd and was aiming my records for them. They were very open to lots of different music being played by Jellybean, who was another great DJ. But we also went into the club when it was empty and tested records on the system. We would go back and forth from my studio on West 37th Street to the Fun House on West 26th Street. That was definitely the case with New Order’s “Confusion.” That was made specifically for the Fun House.

It’s a scene captured wonderfully in that video for “Confusion.” I’ve always thought that was one of the most important documents of New York in the ’80s. Kind of like Taxi Driver for the club scene.

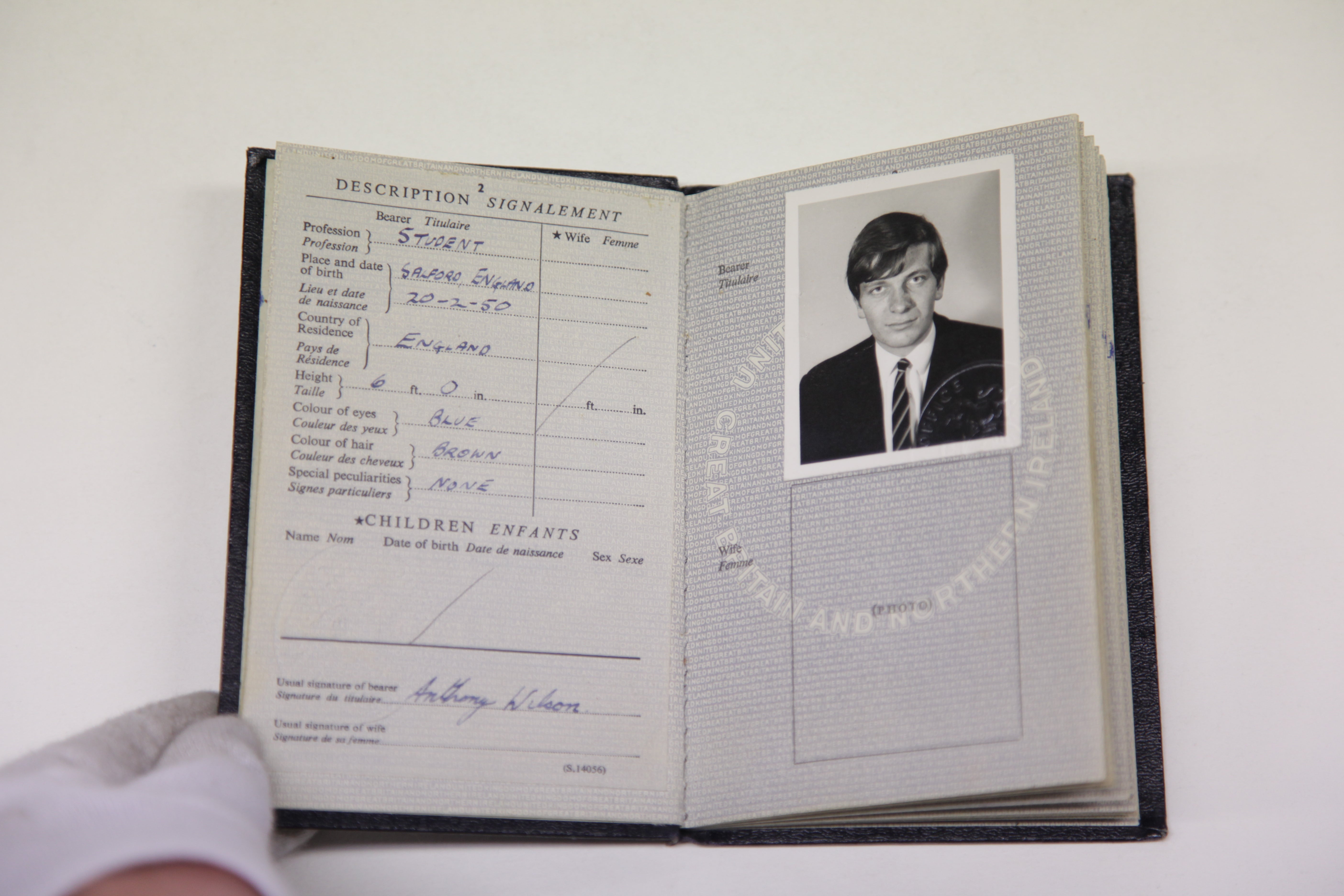

You’re right, man, nothing else captures New York at that time like it. Nobody else thought of doing something like that. [Factory Records founder] Tony Wilson somehow convinced me to be in that video because I really didn't want to be. Without him that would never have happened. I’m so pleased he did convince me, though.

“Confusion” was one of many records where you used the Roland TR-808, the machine you became most associated with. Can you take yourself back to first using it on “Planet Rock”?

I had heard Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” at the Music Factory [on Fulton Street in Brooklyn] and loved that sound. We were going into Intergalactic Studios with Afrika Bambaata but they didn't have a drum machine, nor did I at that time. So we looked in the Village Voice and saw an advert for a man with a drum machine. I called the guy, whose name was Joe, and he had an 808. So we took it to Manny’s Music store to try it out. Then we went into the studio and I programmed the beats with Joe and Bambaataa, and that was the start of “Planet Rock.” It had that Latin feel I loved. Once we made that record we owned that sound for a little while. Then [Jimmy] Jam and [Terry] Lewis began using it and it became their sound. So when I went to do “Breaker’s Revenge,”[from 1984’s Beat Street soundtrack] I switched to the [Oberheim] DMX. I didn’t just want to be known for the 808.

You’ve always thrived on collaboration and bringing people together. When you look back, what projects have you been most proud of?

I would definitely say [the 1985 Artists United Against Apartheid album] Sun City, which we recorded at Shakedown. Steve Van Zandt originally wanted to have four rappers and four rockers but I wanted to make sure it was much more. I really wanted it to be a big statement with the artists we could collaborate with [including Miles Davis, Peter Gabriel, Gil Scott-Heron, Herbie Hancock, Run-DMC, and Keith Le Blanc]. We heard rumors Miles might turn up, then one day he did. It wasn’t like you booked Miles in for 8 p.m. for a session. Sun City was my finest hour as not only was it musically cool but it made a difference, I think.

Growing up against the backdrop of the Vietnam War/Civil Rights struggle, you experienced the power of music as a weapon. Do you think musicians have a responsibility to address what is going on in the world today?

I always thought it was important to give a message in the music. That is why I loved Gamble and Huff and Norman Whitfield creating those dance protest songs. Chuck D famously said rap was “the CNN of the ghetto.” I mean the world is fucked up right now. It would be good if some artists stood up.

Has writing the book made you look back at your life differently or brought things like the Lost London Album sessions into focus?

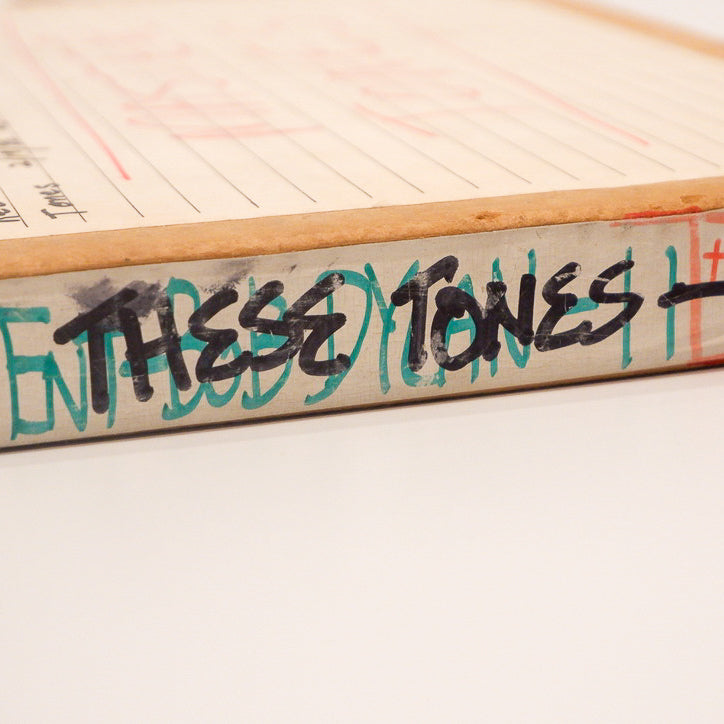

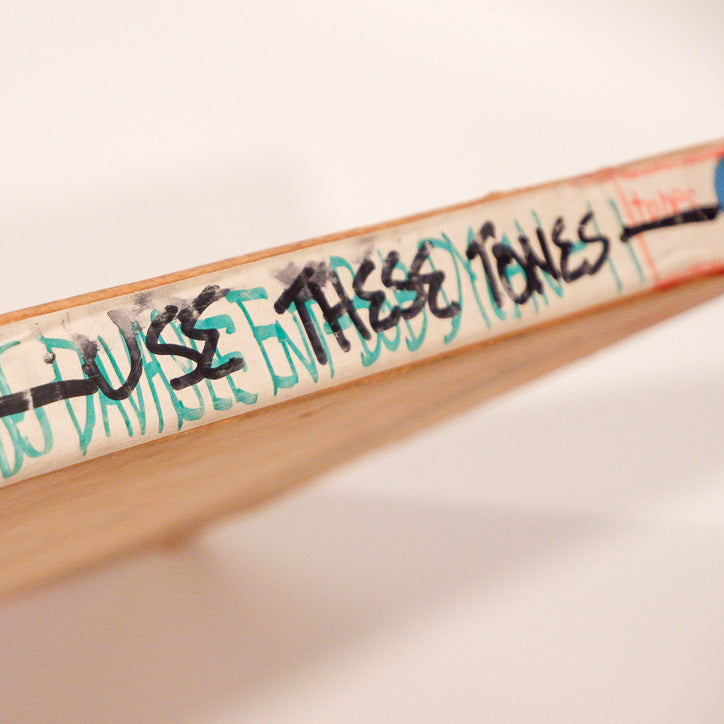

The thing is, without having the photos, films, track sheets, and data on cassettes written by engineers at that time, I wouldn't have been able to write the book in the same way. With all this documentation from back then, it’s enabled me to reconnect with that time and it’s been much easier to go back. Writing the book has been like being a private investigator into my own life.

Don't miss our upcoming collections

We have so much more coming. Sign-up to any of the below to make sure you don't miss out.