THE BOOTSY COLLINS COLLECTION

As Bootsy gets set to celebrate his seventy-third birthday he’s opening the doors to the Ark, clearing space and combing through the artifacts of his past—making them available for the first time to you.

- Bid on items from Bootsy's personal collection

- Secure limited-run products

- Deep-dive into incredible stories

THIS COLLECTION IS NOW CLOSED.

12PM EST • WEDNESDAY, NOV. 13 2024

Auction Items

Bid on some of the most unique and sought after music items from Bootsy Collins

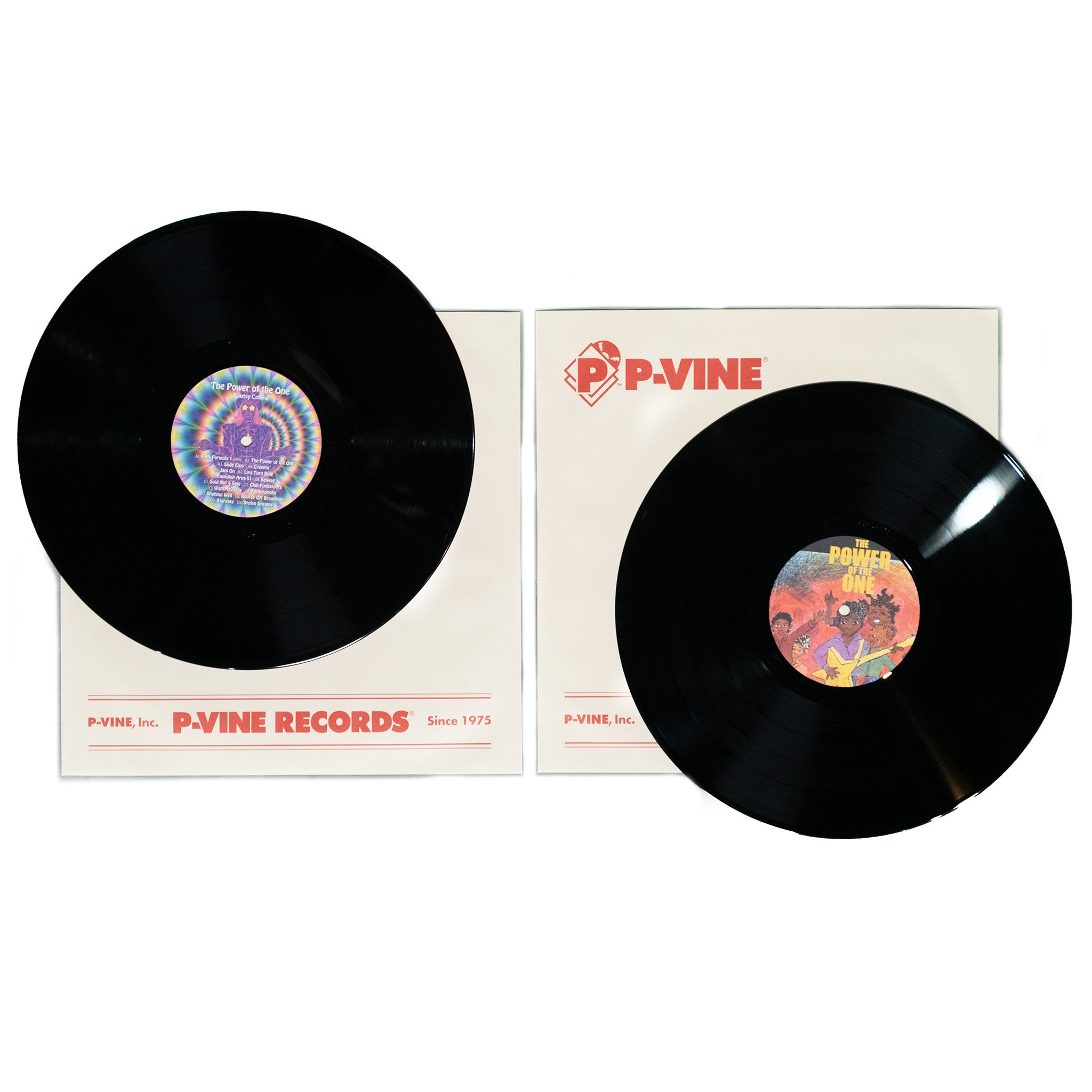

LIMITED EDITION PRODUCTS & JOURNALS

Limited-run, custom-made collectibles from Bootsy Collins & Wax Poetics, as well as back issues from our store

BUY-IT-NOW ITEMS

Fixed-price items directly from Bootsy's personal collection

Bootsy Collins is the living, breathing embodiment of funk.

From his early ’70s run with James Brown’s original J.B.’s to his cosmic chemistry with George Clinton in Parliament-Funkadelic and his superstar bandleader era with Bootsy’s Rubber Band, the Cincinnati, Ohio-bred bassist has brought the bottom to so many of the funkiest recordings ever made.

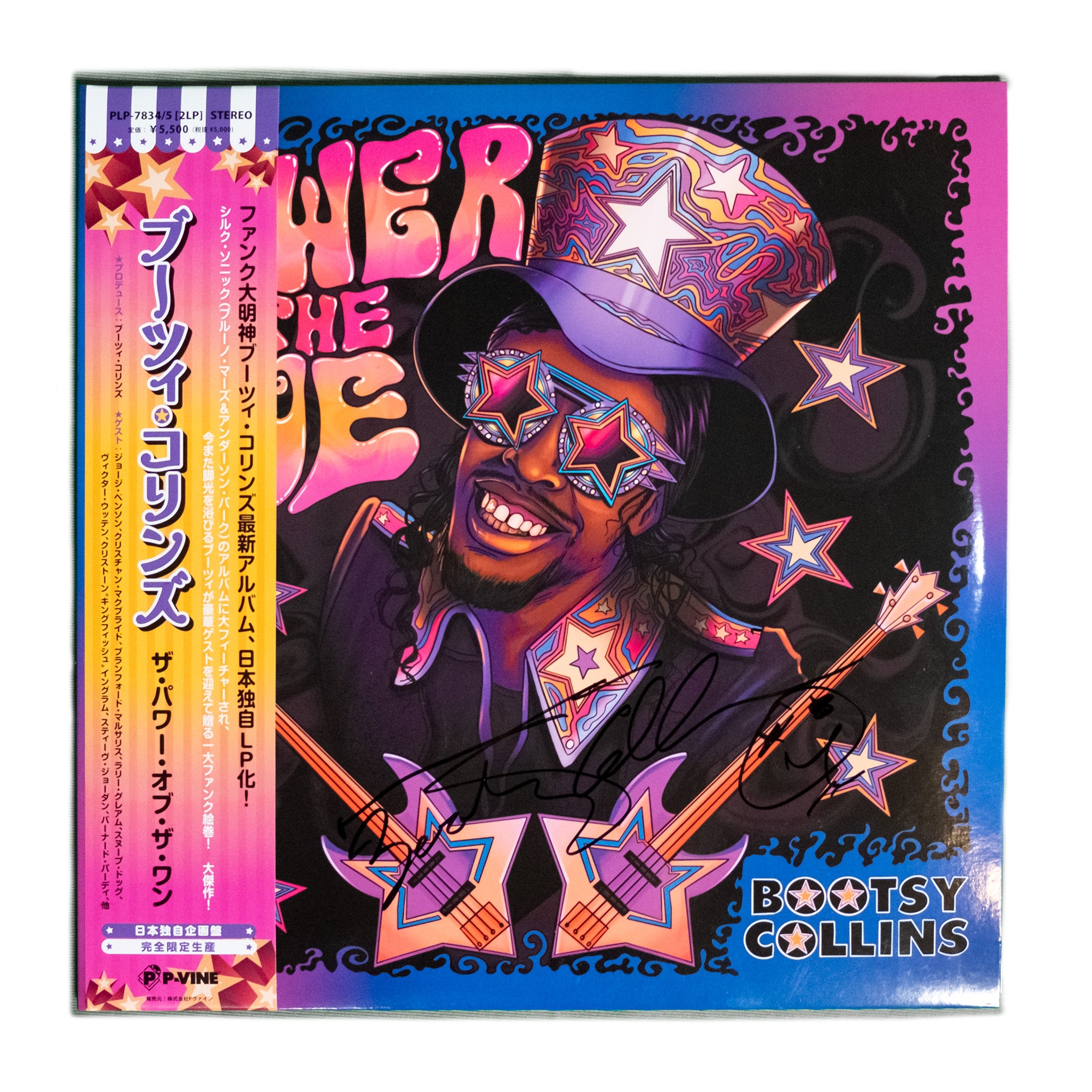

Nearly a half-century after Mothership Connection, Bootsy’s influence still courses through contemporary music, from Childish Gambino’s “Redbone,” a straight-up homage to the 1976 Bootsy’s Rubber Band classic “I’d Rather Be With You,” to Anderson .Paak and Bruno Mars’ Grammy-winning 2021 modern-funk opus An Evening with Silk Sonic, which featured Bootsy as its narrator and honorary guest host. He’s been the not-so-secret ingredient in so much West Coast hip-hop, from the samples driving classic tracks by Eazy-E (“We Want Eazy”) and 2Pac’s (“Str8 Ballin”) to the verbal panache and playful personas of Snoop Dogg and the late Shock G. He’s the blueprint for Flea, Thundercat, and every other outlandish, mononymous bass god that’s come up in his wake.

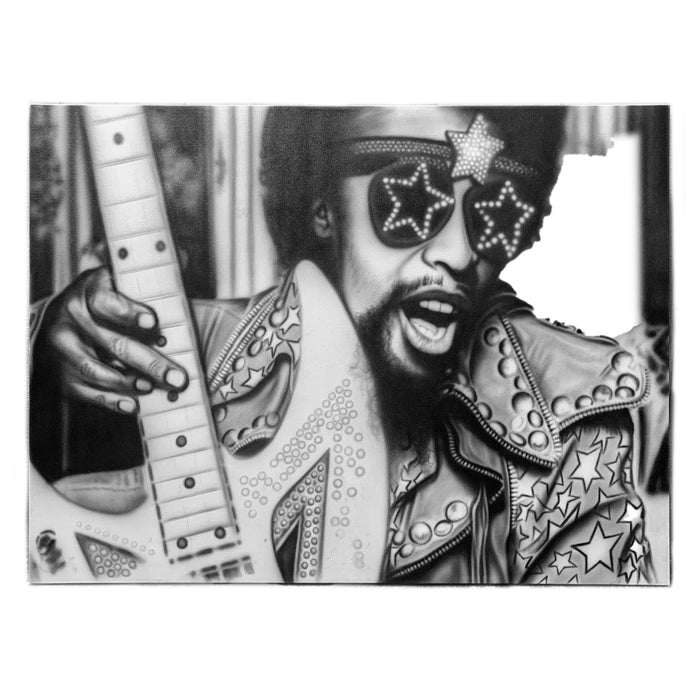

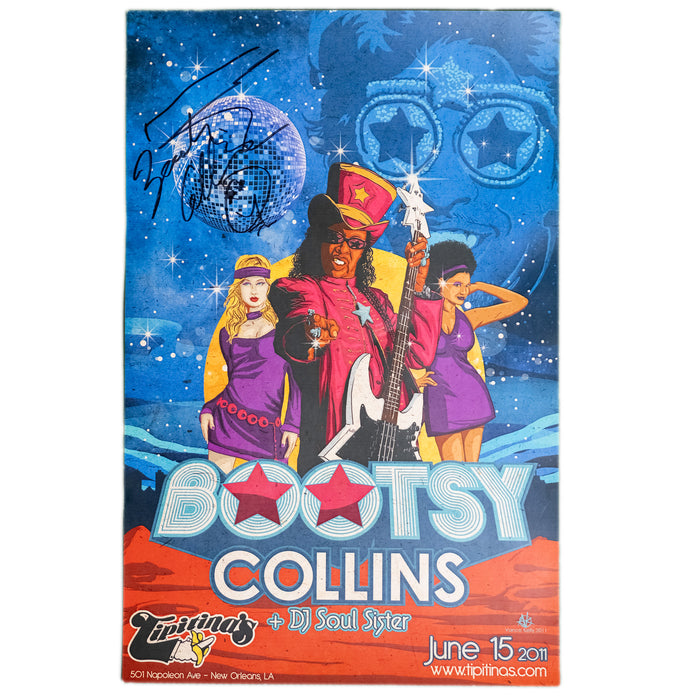

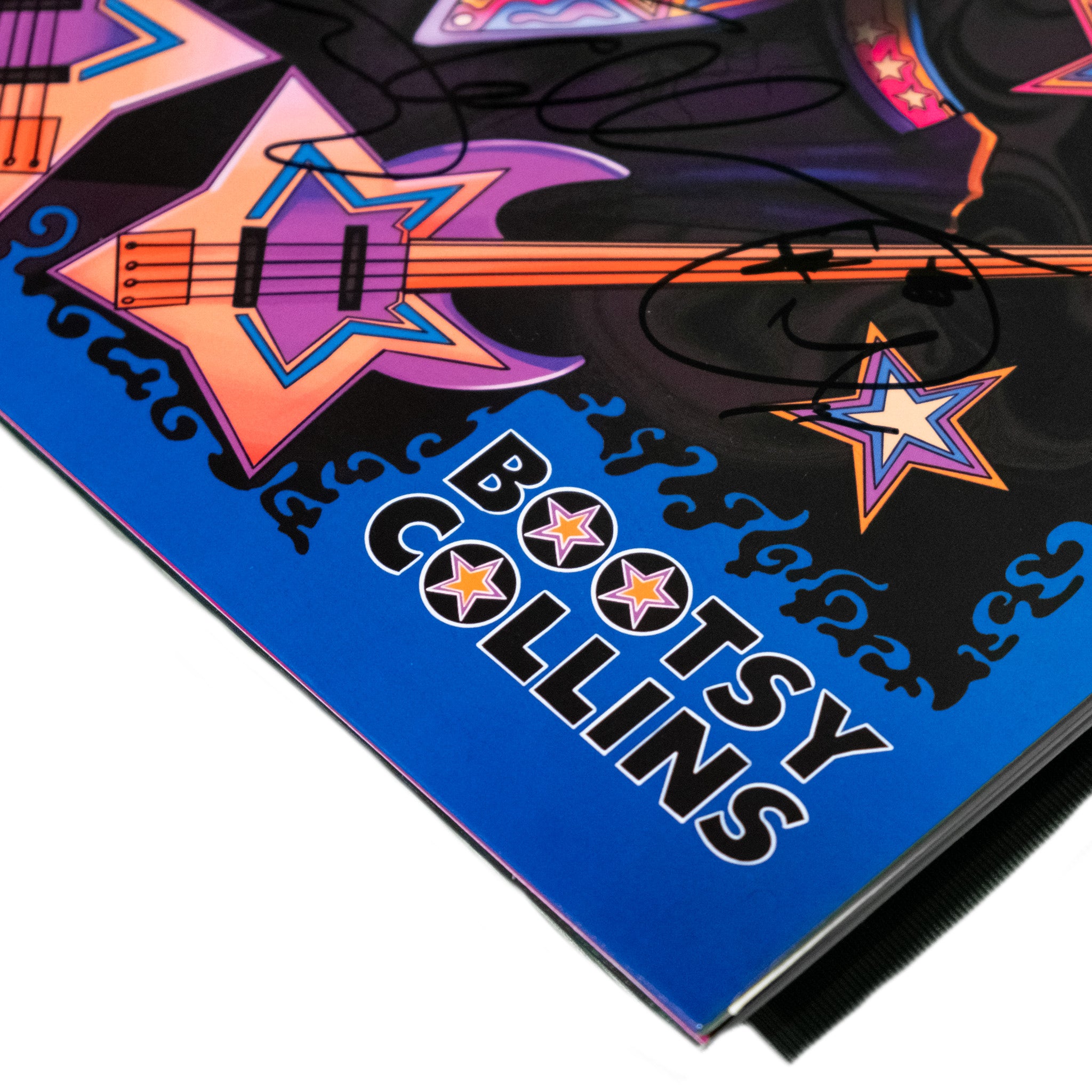

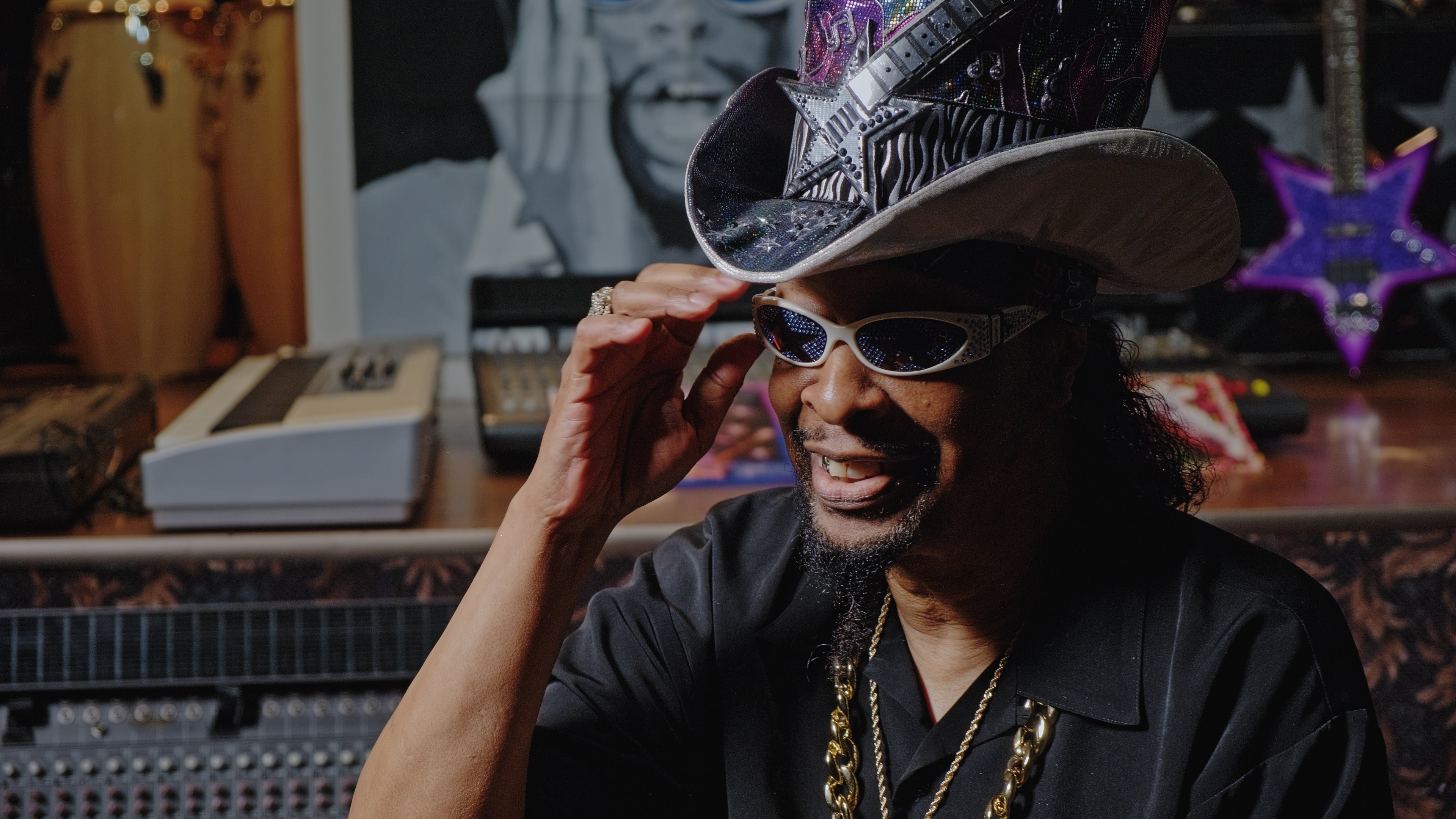

When it comes to representing funk in the flesh, Bootsy’s personal style is truly one with The One. Like a character from a Dr. Seuss book come to life, his signature look—star shades, Mad Hatter-style top hats, heavyweight platform boots, and five-point, star-shaped “Space Bass” guitar—has made him an instantly recognizable icon of pop culture.

The tapestry of Bootsy’s rich and colorful career comes into deep focus inside the barn-turned-rehearsal-studio, soundstage, and personal museum which he calls Noah’s Ark, or the Ark for short. Located opposite his home—the “Boot Cave”—on a rural, twenty-acre spread east of Cincinnati that he calls the Bootzilla Rehab Center, the cavernous space overflows with the accouterments of a life spent funkin’. As you enter the Ark, a life-sized promotional cutout from the 1979 Bootsy’s Rubber Band album, This Boot Was Made For Fonk-N, greets you from overhead. Mannequin recreations of Bootsy’s friends and collaborators Buckethead and Snoop share wall space with a menagerie of guitars and basses, and an expansive series of rock-star portraits (James Brown, Bob Dylan, Michael Jackson, Alice Cooper) purchased from Ohio artist Neal Hamilton.

“What this represents is how I see the world,” Bootsy says of the Ark, spanning the room behind him with a broad sweep of his arm. “It’s not just a genre. I love it all.”

As Bootsy gets set to celebrate his seventy-third birthday—and his sixtieth year in music—he’s cleaning house and clearing space. Which is why on a windy, rainy Friday in September, with Hurricane Helene knocking on southern Ohio’s door, he’s opened up the doors to the Ark to let us comb through the artifacts of his past—to “rehash some trash,” as Bootsy puts it. There’s a saying about one man’s trash, though…

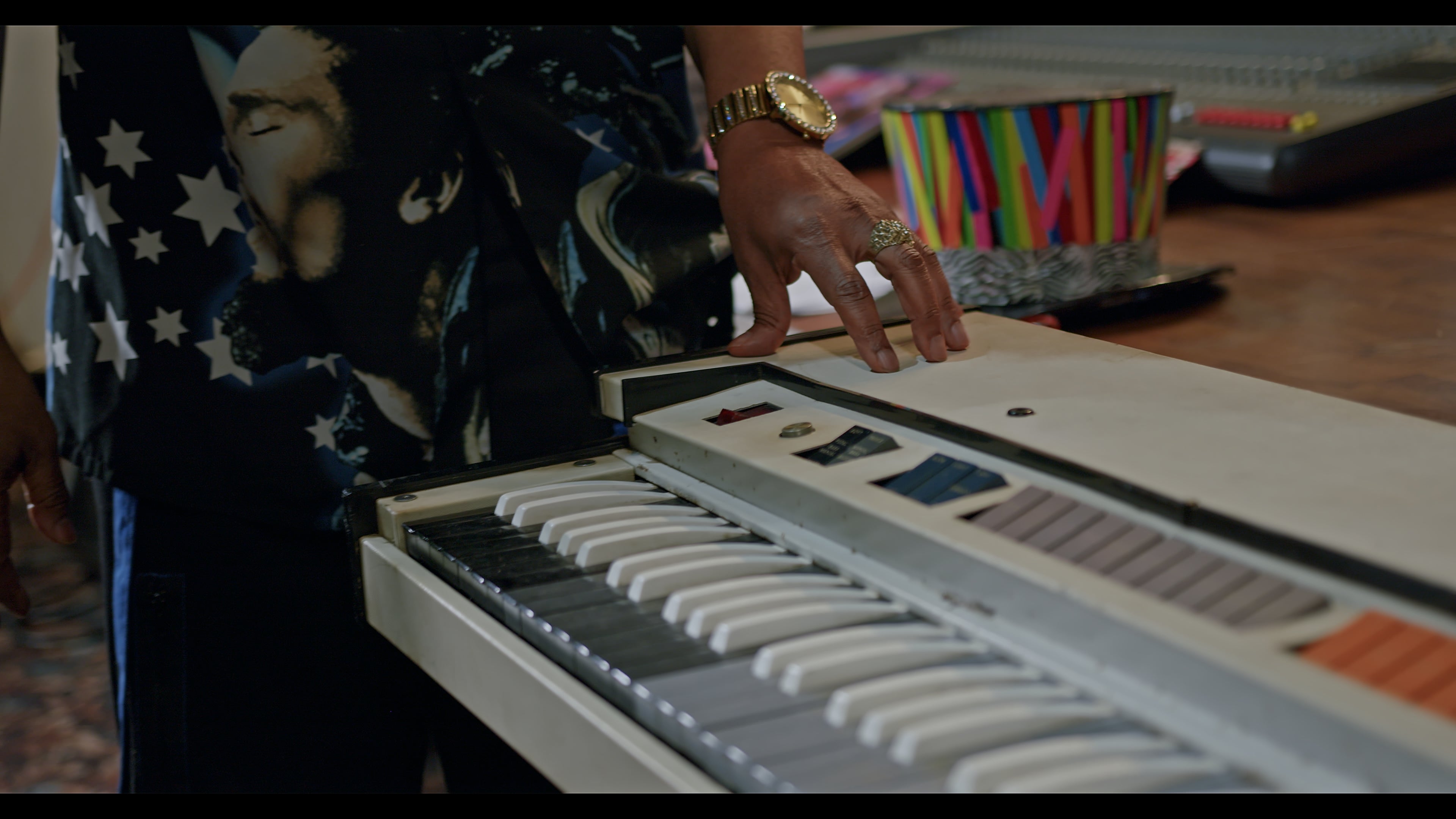

Bootsy Collins doesn’t walk through the Ark so much as glide, stopping to ponder and comment on the items that his wife and manager, Patti, has pulled for our review. There’s the “Jam Fan” from the These Boots Were Made for Fonk-N era, a promotional cooling aid distributed at Bootsy’s Rubber Band concerts in 1979; a late-’60s vintage Farfisa combo played on tour by Bernie Worrell; a three-piece Duck Tape suit—tophat included—that the adhesive company custom made for him to wear to the Apollo Theater on his sixtieth birthday.

Here inside the Ark, Bootsy sports a toned-down version of his classic look: leopard-print boots, star shades, a rhinestone tophat with a miniature Space Bass on the crown. Asked about the origins of his personal style, he takes us back to his humble beginnings in Cincinnati’s West End.

“The first look I had, I didn't really create,” Bootsy remembers. “My mother would take me to the Goodwill, and we all would have to pick clothes to go to school in. They never matched, or they were never cool clothes, you know. When I wore that stuff, the other kids would laugh, and I finally found out how to laugh at this mess myself. Once I figured out, ‘Damn, this is looking kind of weird,’ that's what got me messing with the fashion thing. I loved the entertainment look: Little Richard, Elvis, Sly [Stone]. All these mugs was coming out, and they was the bomb.”

Bootsy’s number-one hero in those days was his late brother, Catfish, who’d later join him on his journeys with James, George, and Bootsy’s Rubber Band. Eight years Bootsy’s senior, Phelps Collins was already ensconced in Cincinnati’s live music scene when a young Bootsy started sneaking into his room to emulate him on guitar. Soon, a thirteen-year-old Bootsy was trying to impress his big bro with the skills he’d picked up playing with a local gospel band, the Christian-Aires, hoping to secure a spot in Catfish’s group. Bootsy would find his “in” after retrofitting his $29 guitar into a makeshift bass. “Once I got to hook up with him, that is when I knew we got something.”

THE JAMES BROWN DAYS

Together, Bootsy and Catfish would form the Pacemakers, a cauldron of Cincinnati talent whose members also included Philippé Wynne, the future lead vocalist of the Spinners, and drummer Frank “Kash” Waddy. The Pacemakers never released a record: before they could, Bootsy, Catfish, and Kash, along with trumpeter Clayton “Chicken” Gunnels, were scooped up by James Brown—who’d come upon the band through their session work with his then-label, Cincinnati’s King Records—and dubbed the James Brown New Breed Band, later abbreviated as the J.B.’s.

This Cincinnati-fied version of the J.B's lasted only about a year, but they set a high bar, laying down the grooves on some of James’s hardest-charging recordings, including “Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine,” “Super Bad,” “Soul Power,” and “The Grunt,” while holding down the Godfather nightly during one of his busiest and most electrifying runs as a performer.

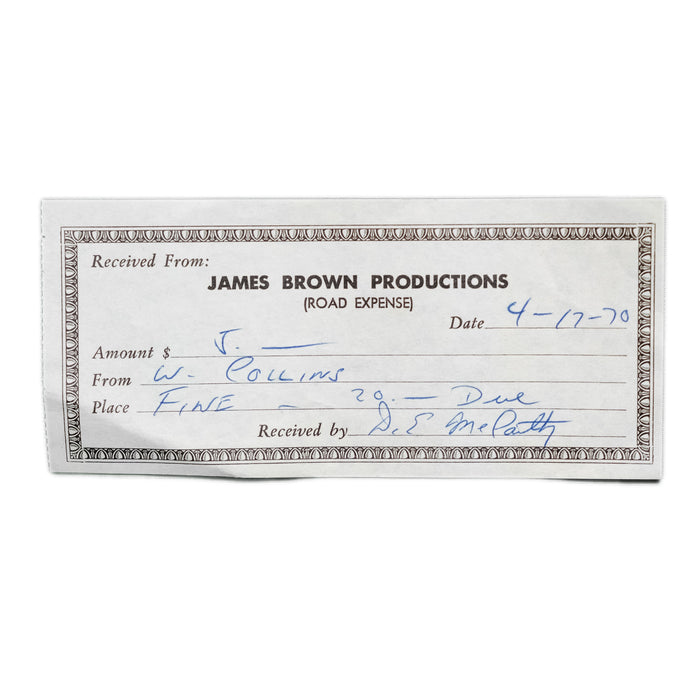

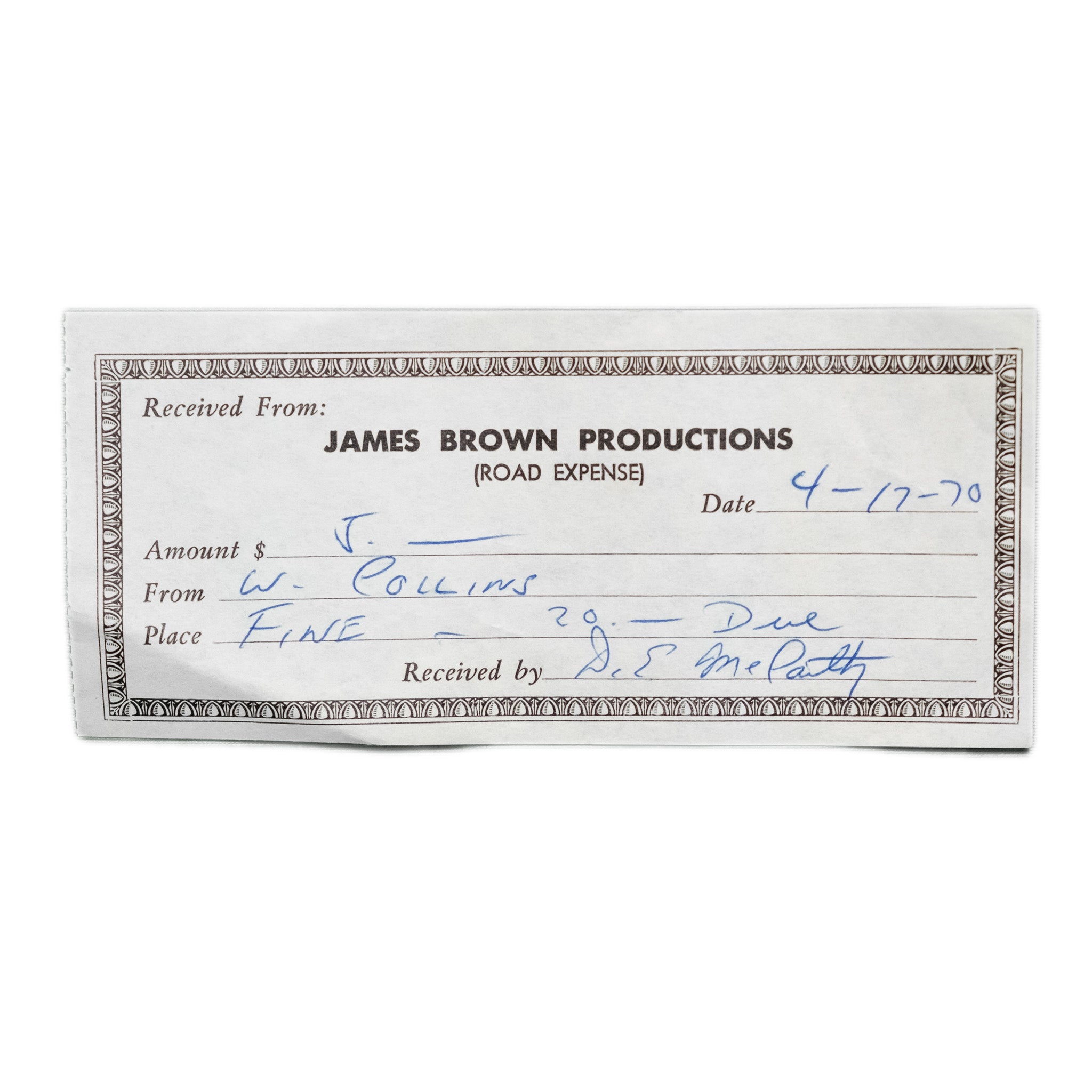

Back in the present day inside Noah’s Ark, a fine slip from James Brown Productions dated April 17, 1970—just weeks after Bootsy and crew made their debut with James in Columbus, Georgia—offers a rare and illuminating window into Bootsy’s brief run with the Godfather of Soul.

Bootsy can’t recall why he was fined five bucks that day, or how his total debt hit twenty dollars, but the sight of the slip, signed by James’s long-time business manager and accountant David McCarthy, sends him into gleeful laughter. Reprimand was just part of the deal when you signed up to play in James’s band, and a free-spirited Bootsy, just eighteen years old at the time, would naturally run afoul of the boss more than most.

“Yeah, I remember these days, man,” Bootsy says. “But I wouldn't trade them for the world. Twenty bucks to play with James? I'll do it! I'll do it over and over and over.”

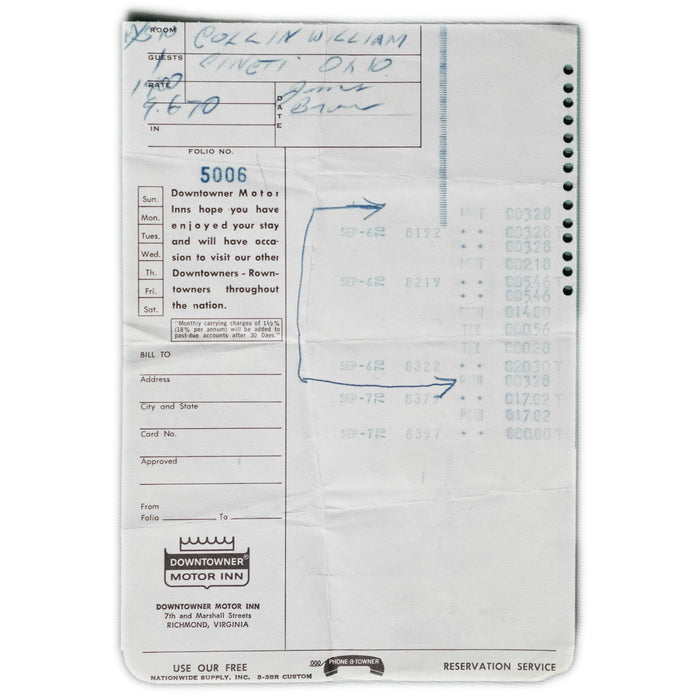

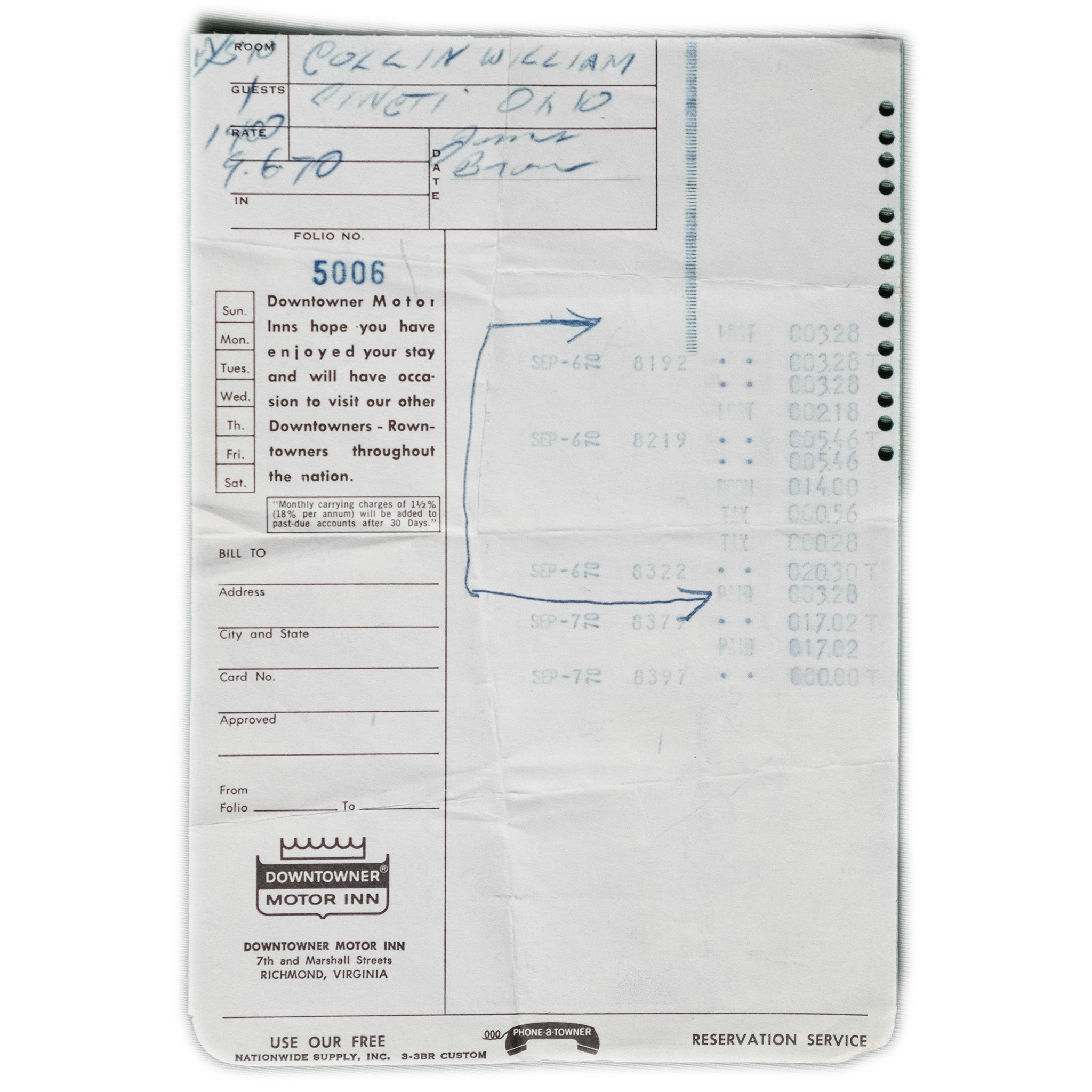

Deeper still in the stash is another receipt, signed by James, from a stay at the Downtowner Hotel in Richmond, Virginia, dated September 6, 1970. That was the night of a two-set engagement at the Mosque, known today as the Altria Theater, a regular haunt of James’s in those days. “This was our stomping grounds, man,” Bootsy says. “A lot of times, [James would] like for us to leave right after the gig, because he wanted to go to a studio, or to rehearse...He would do anything to keep us from having a good time without him. So we loved it when we got a chance to stay overnight, and [at] this particular hotel we got a chance to stay overnight, and we had a blast.”

BOARDING THE MOTHERSHIP

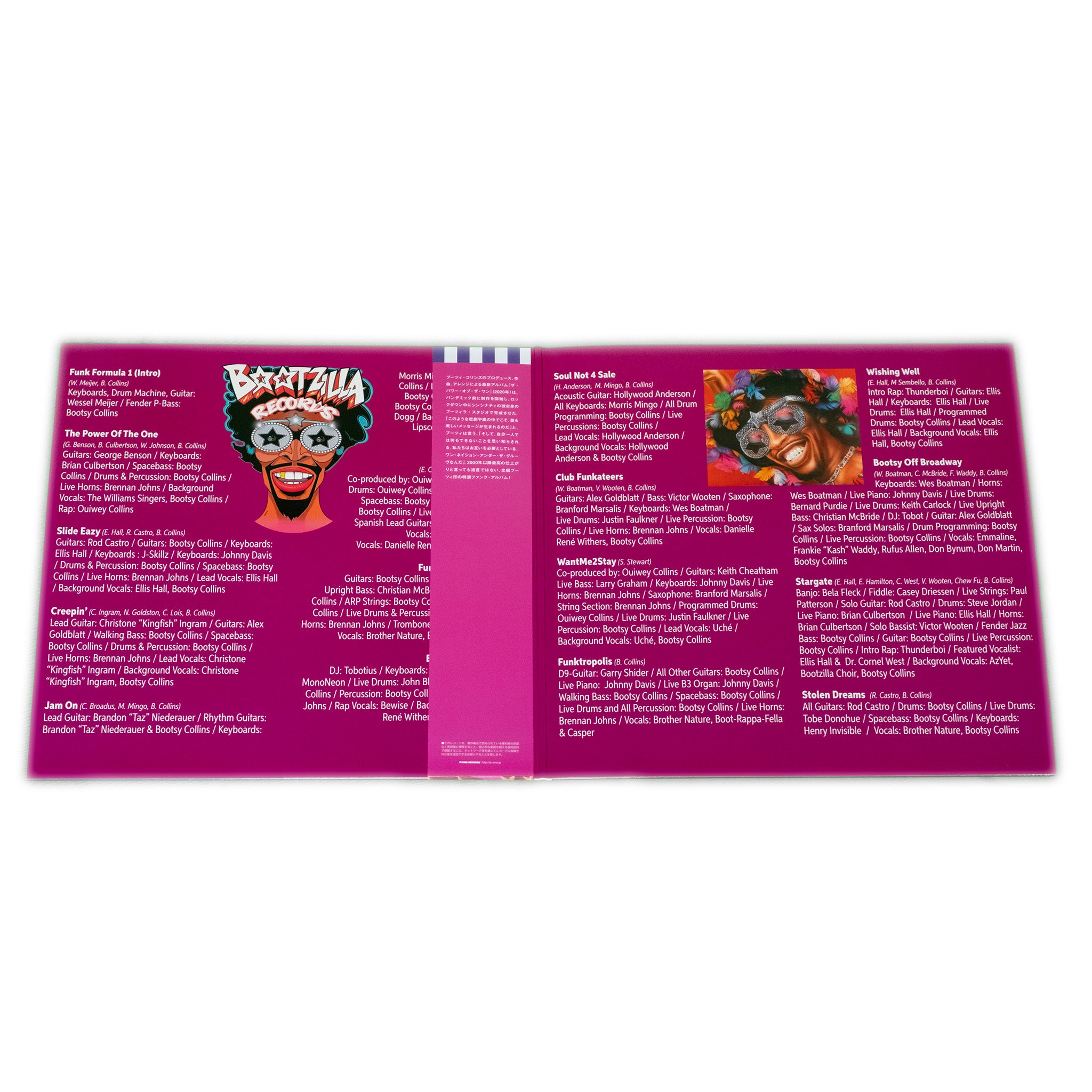

Inside the expansive Afrofuturist universe George was building around Parliament, Funkadelic, and other assorted side projects and splinter acts, Bootsy was like a kid in a candy shop. Beyond the incredible musical output of this period, which saw him co-write classic Parliament anthems like "Up for the Down Stroke," "Tear the Roof Off the Sucker (Give Up the Funk)" and "Flash Light," Bootsy took the opportunity to develop his signature look with fashion designers Larry Legaspi, Calvin Murphy, and Tom Wojciechowski (aka Tom the Leatherman). He bonded with illustrators Pedro Bell and Overton Loyd, whose fantasy “bop art” helped define the P-Funk visual aesthetic, and recruited Michigan guitar tech Larry Pless to build the first Space Bass in 1975 from a design Bootsy sketched on a napkin.

“It was just like another musician [in the band], but it was an artist, doing the design and putting things together,” Bootsy says of these collaborations. “The videos before the concerts, the comic books in the albums—All of that stuff was like gold to us. That was just like the music [but] a whole ‘nother avenue. And we loved to do it.”

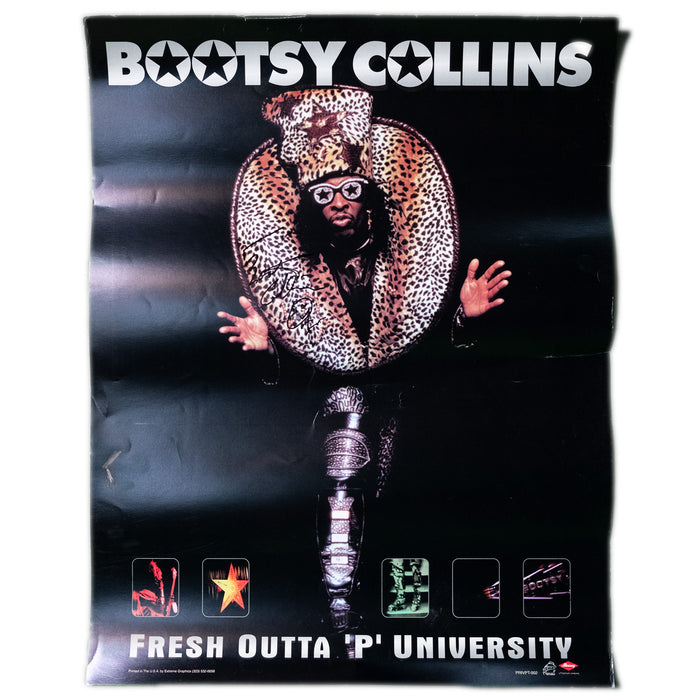

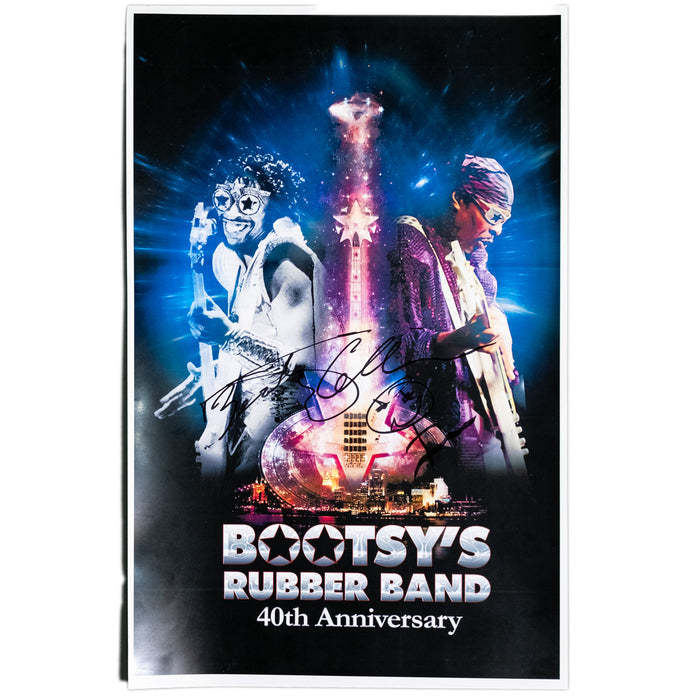

With his star on the rise in 1976, Bootsy got the opportunity to form his own P-Funk offshoot, Bootsy’s Rubber Band. Tapping Catfish and his Cincinnati crew from the Complete Strangers, along with P-Funk mainstays like Gary “Mudbone” Cooper and Robert “P. Nut” Johnson, the group dropped four deliriously funky albums during an epic four-year run from ‘76 to ‘79, while opening up on tour for Parliament-Funkadelic during the collective’s Mothership-fueled stadium peak.

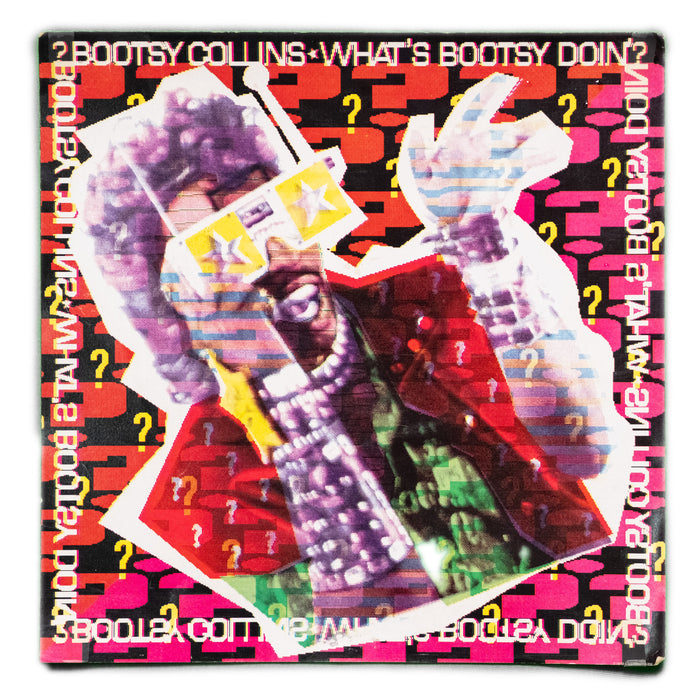

Burnout naturally ensued, and Bootsy would go on to spend much of the ’80s recovering from the excesses of the previous decade. (He would manage one last hit with Bootsy’s Rubber Band, in 1982’s electro-funk workout “Body Slam!,” before putting the group on extended hiatus.) He re-emerged with What’s Bootsy Doin’? in 1988, the same year Dr. Dre sampled the title track from 1977’s Ahh... The Name is Bootsy, Baby for Eazy-E’s “We Want Eazy.” He’d also feature in Eazy’s music video, setting off a rich run of cameos and collaborations, including appearances on Keith Richards’ Talk is Cheap (1988) and Malcolm McLaren's Waltz Darling (1989) and, most memorably, the video for Deee-Lite’s worldwide dance hit “Groove is In The Heart.”

The ‘80s and ‘90s saw a trend towards home recording, and Bootsy, then working frequently with innovative New York producer Bill Laswell, was an early adapter, amassing a small arsenal of mixing consoles, samplers, and digital keyboards like the Roland DX7. Over the last twenty-five years, the majority of his projects —right up to his latest, Album of the Year #1 Funkateer (Bootzilla/Equity Distribution)—have been created largely from the comfort of the Bootzilla Rehab Center.

While Bootsy has no shortage of creative partners to tap into these days, there was a time when he had to seek them out himself in order to bring his visions to life. He recalls hitting the pavement in New York City in the early ’70s and looking for someone—anyone—who’d help him bring his Space Bass sketches into three-dimensional reality.

“Everybody on 48th Street turned me down,” Bootsy recalls, referencing the Manhattan strip once known for its cluster of music shops. “I was a youngster and I’m out here just rapping. I hadn’t made it. So they felt like, ‘This is just a one-off.’”

Bootsy has worked with various luthiers and manufacturers on new evolutions of the Space Bass since Larry Pless’ original model in 1975, but for years he resisted offers to mass produce his signature instrument. “My whole thing was, ‘I’m the only one that got a Space Bass, man,’” Bootsy says.

After producing a custom Space Bass with 165 LED lights for Bootsy in 2012, German manufacturer Warwick approached him about bringing a consumer version to market, and this time he agreed. Two hundred units of the Warwick RockBass Artist Line Bootsy Collins Space Bass, with “special purple Bootsy finish,” have shipped since 2014. Bootsy, of course, got the first one. Now, that very bass, direct from Noah’s Ark, is among the funk delights Bootsy has brought out from his bag for the inaugural edition of Wax Poetics Collections.

Dig in, baby baba.

Secure your limited edition bootsy x wax poetics t-shirt

Only available until November 10