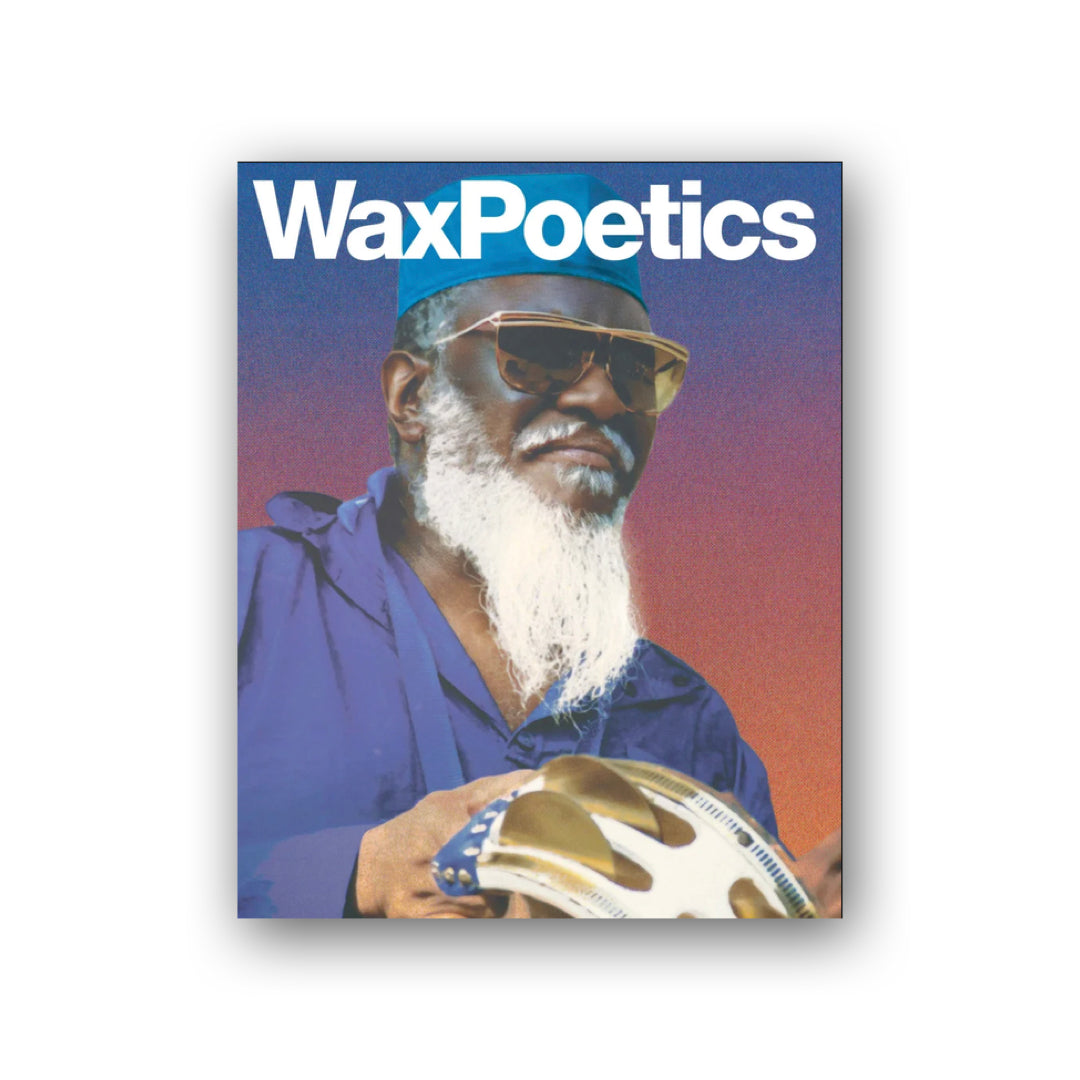

Pharoah Sanders Add to favourites

Couldn't load pickup availability

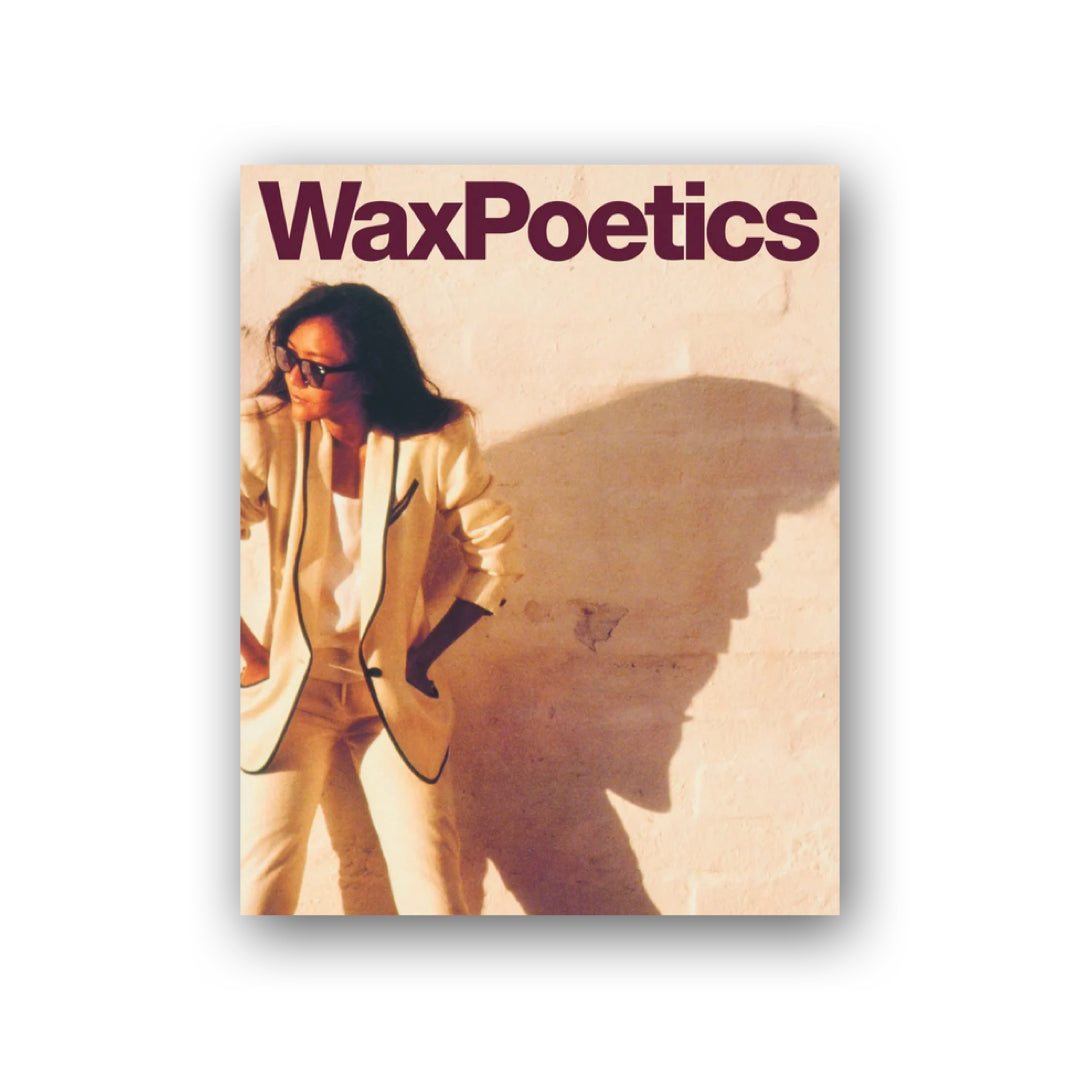

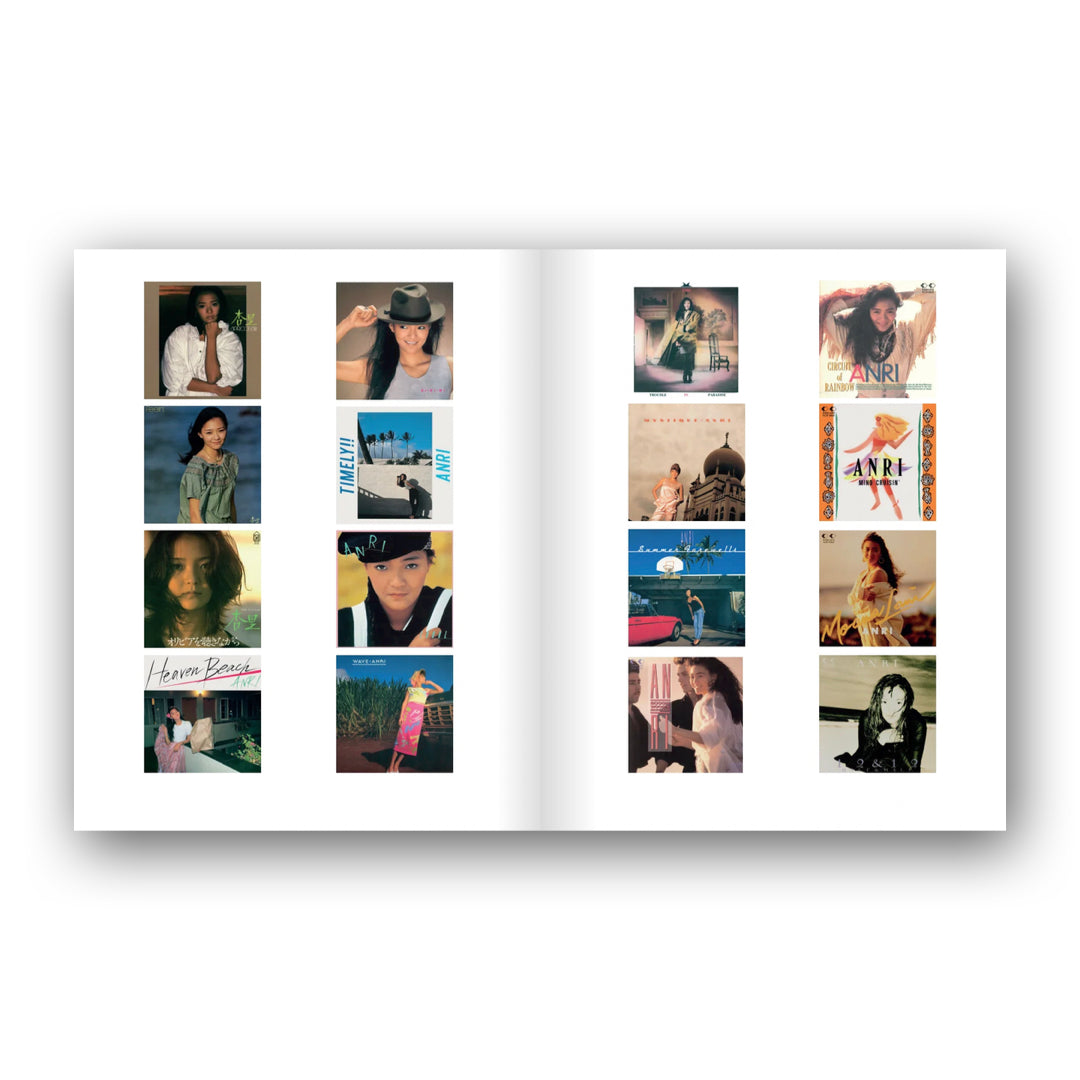

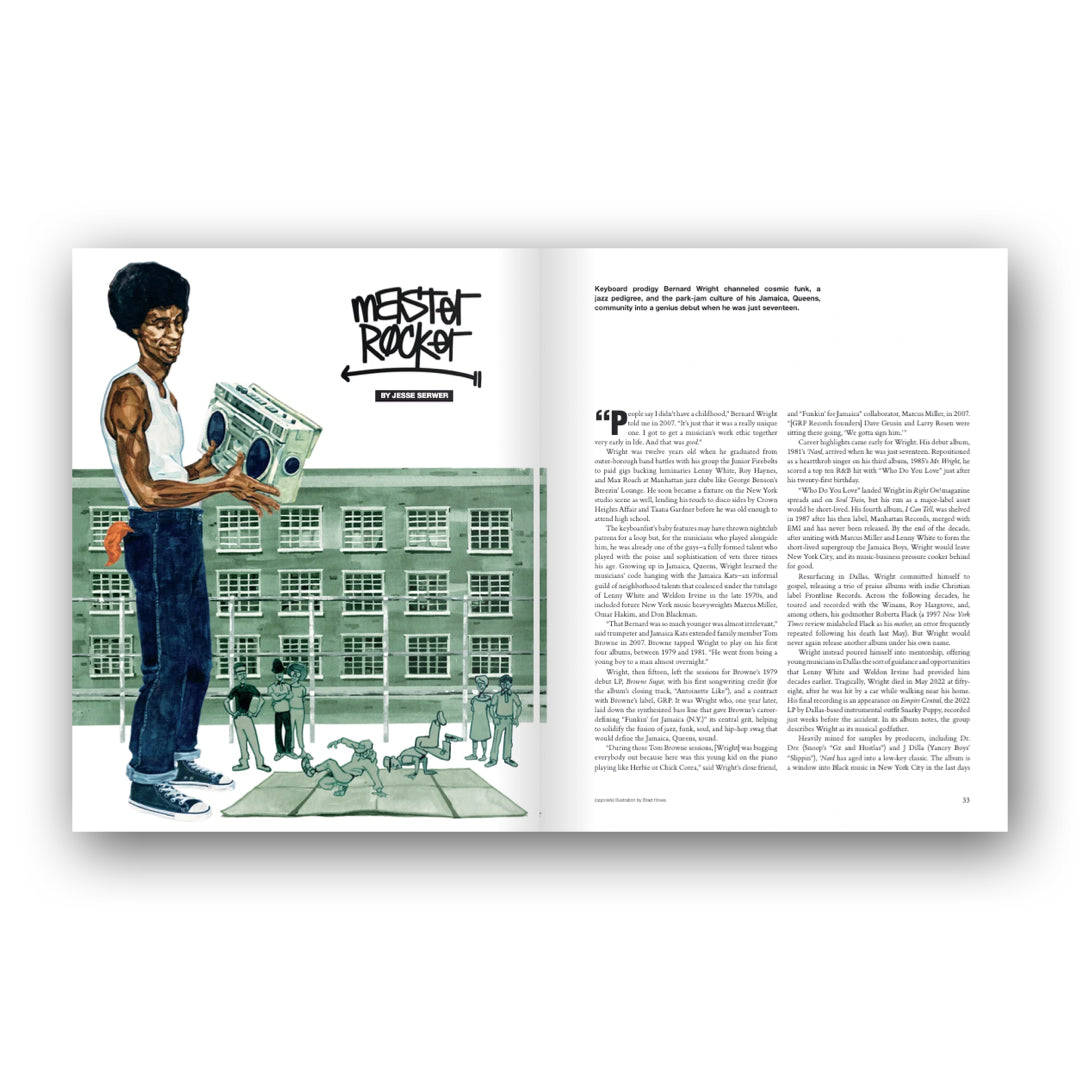

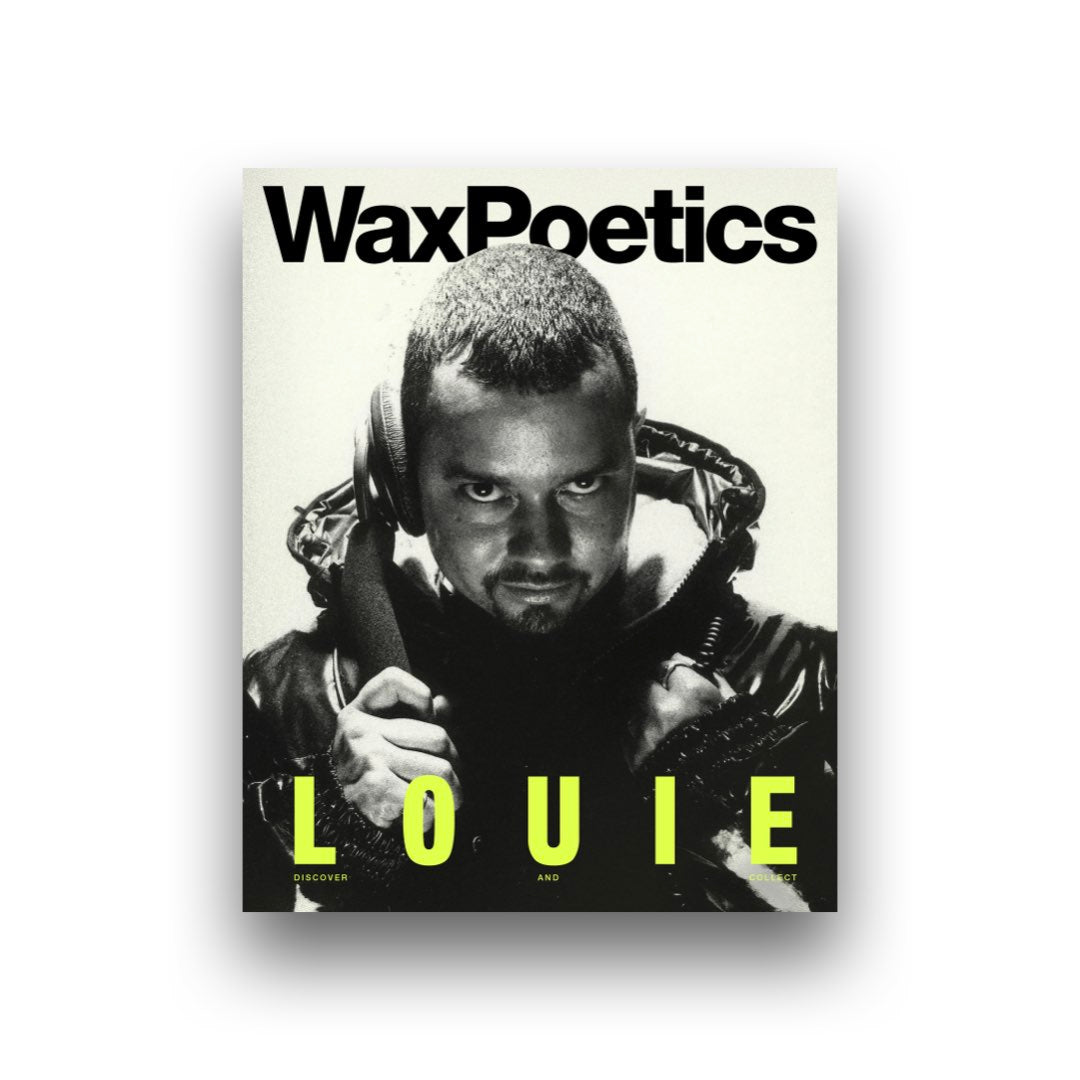

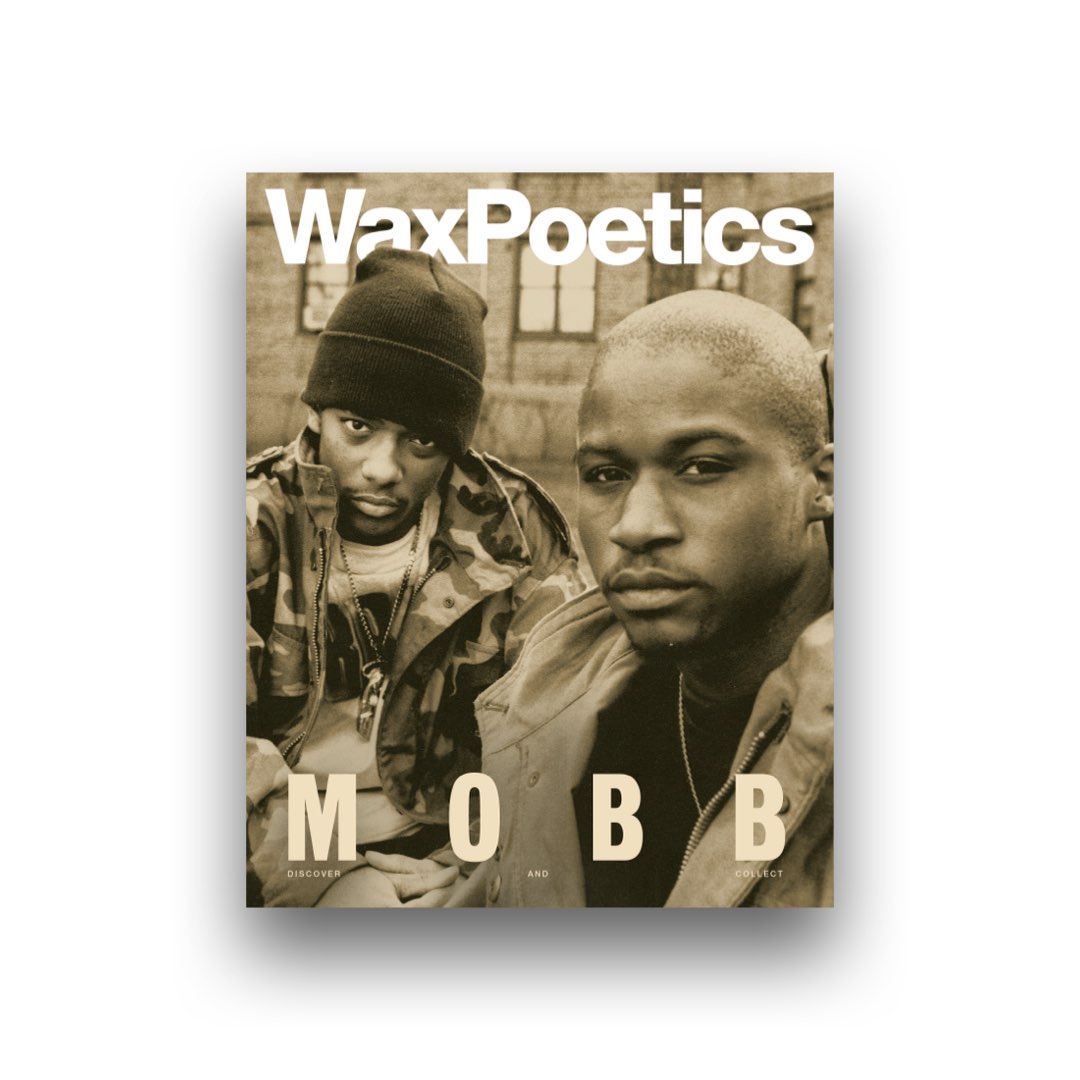

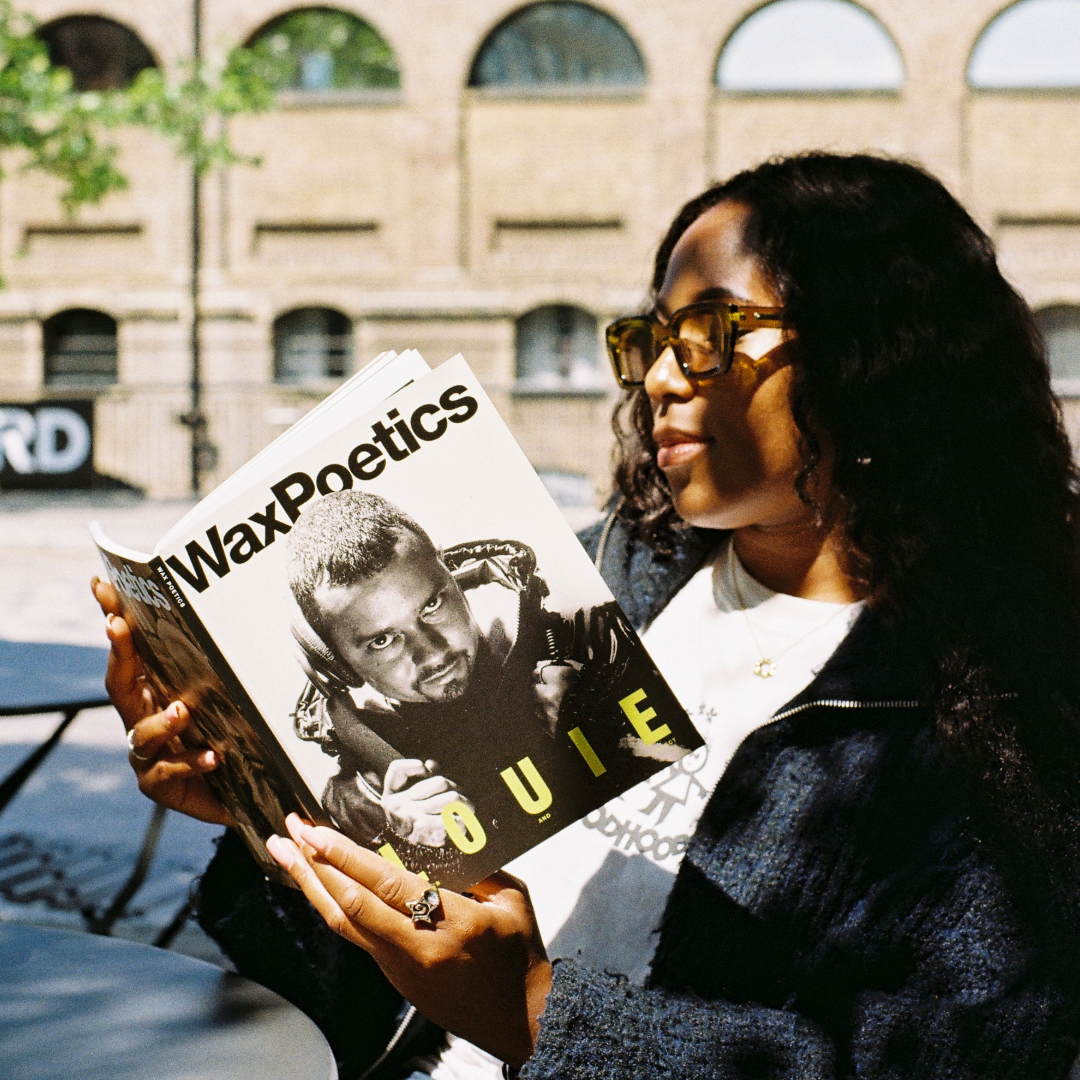

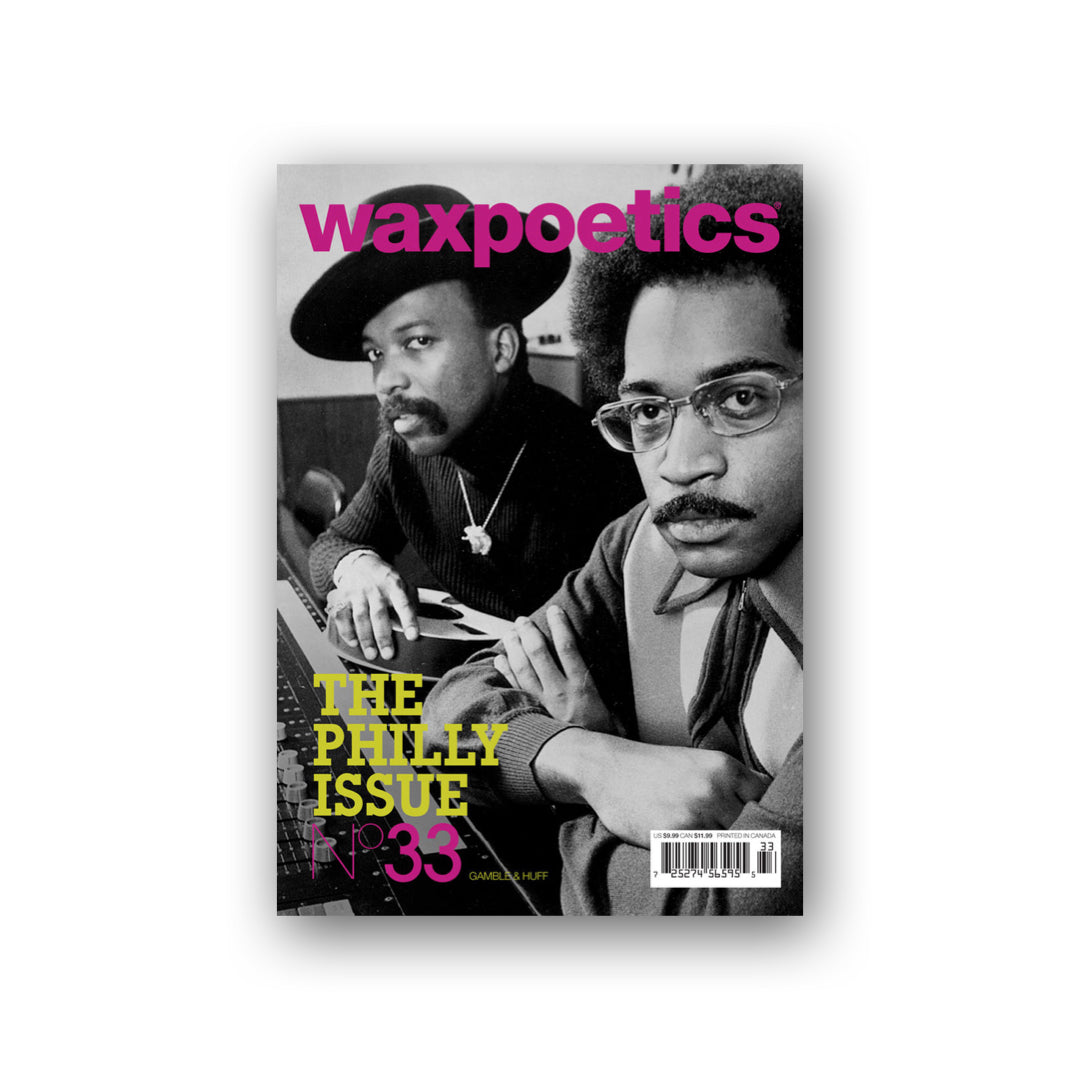

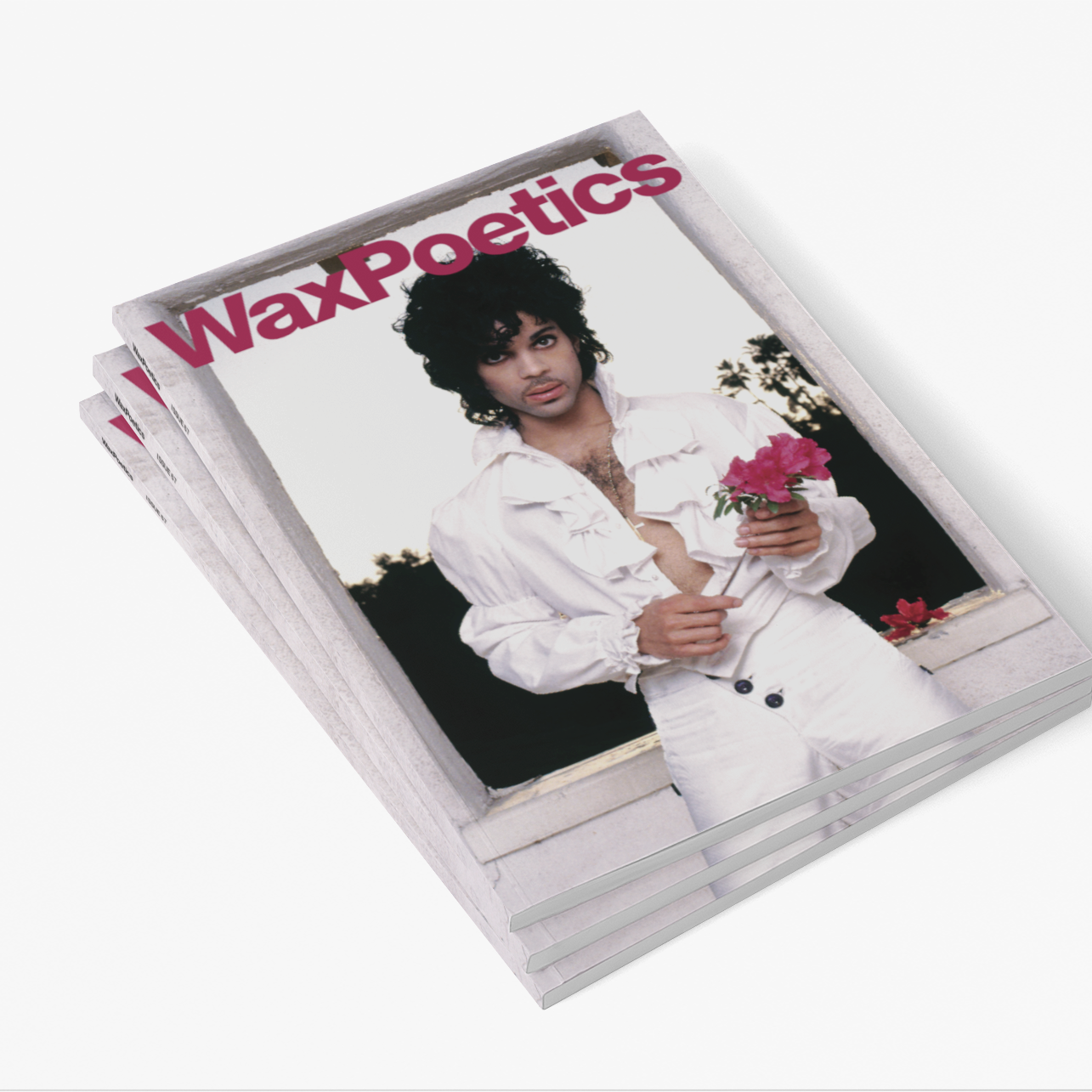

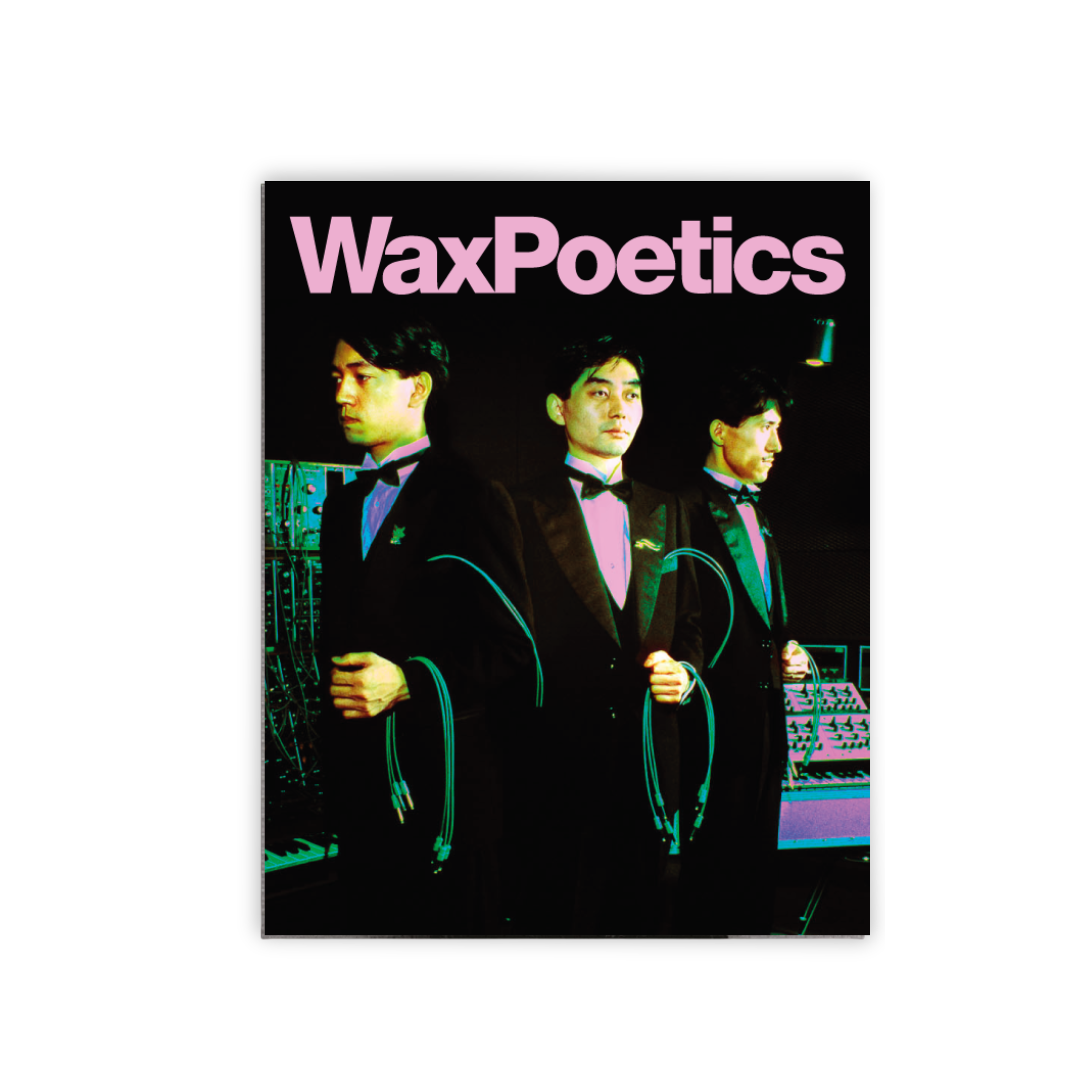

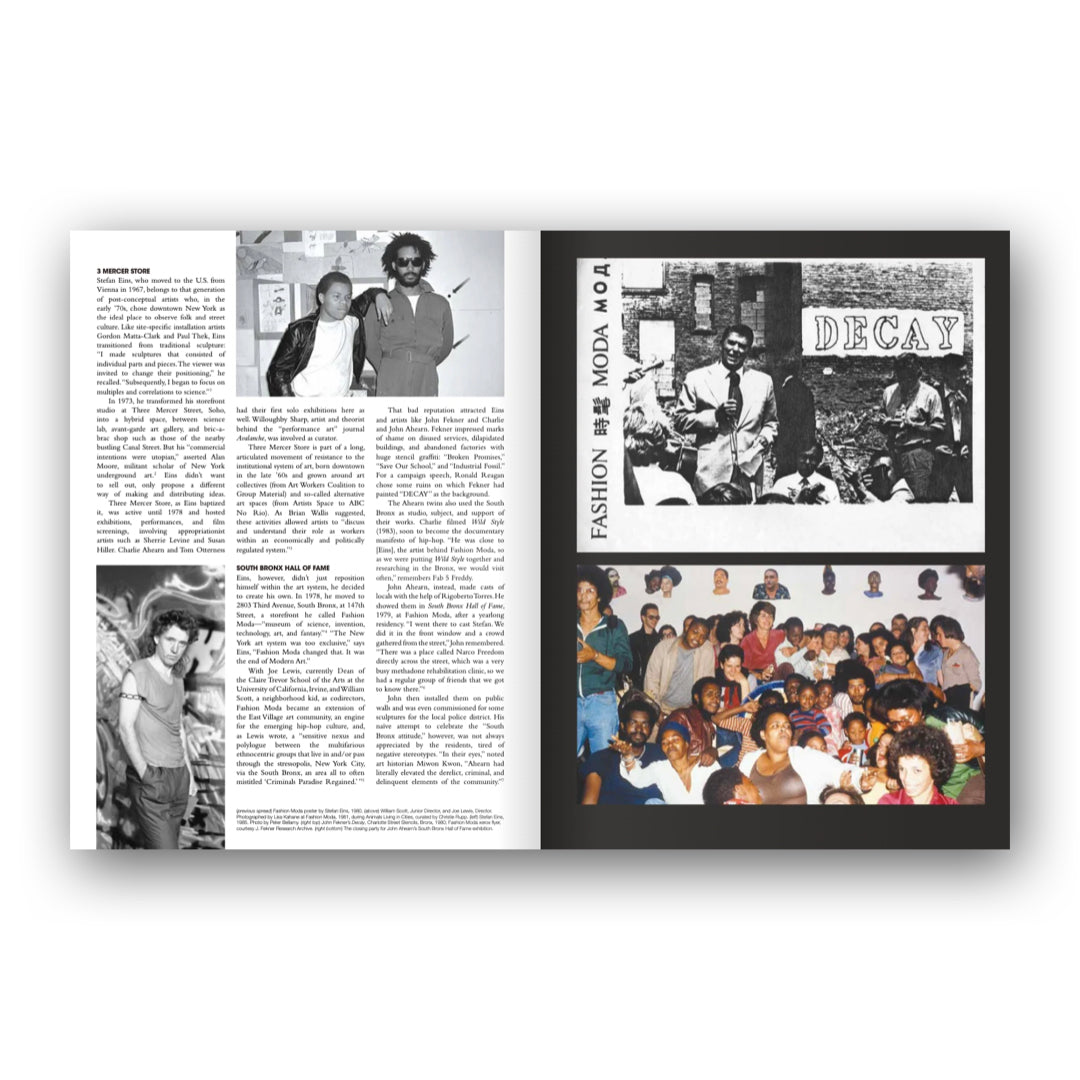

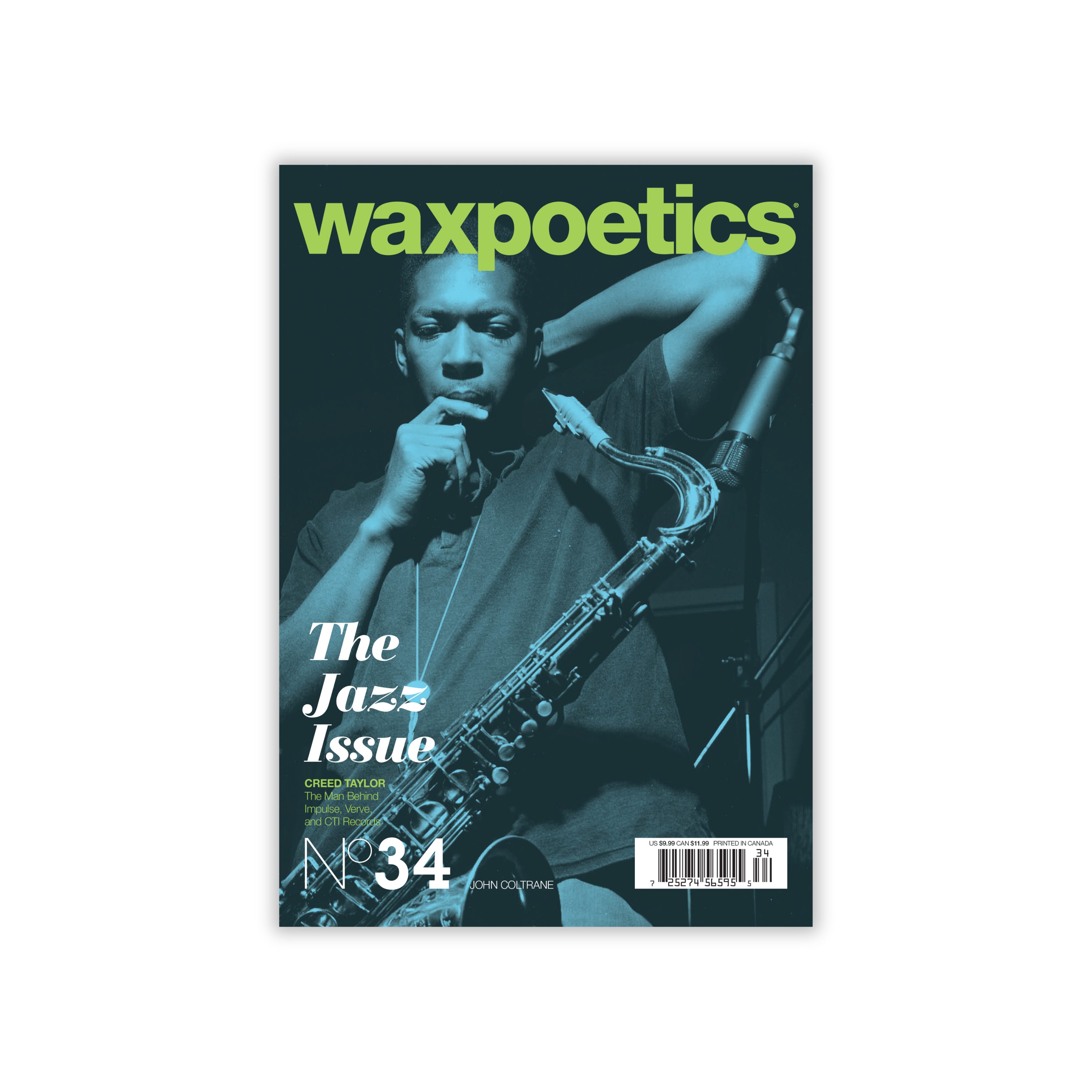

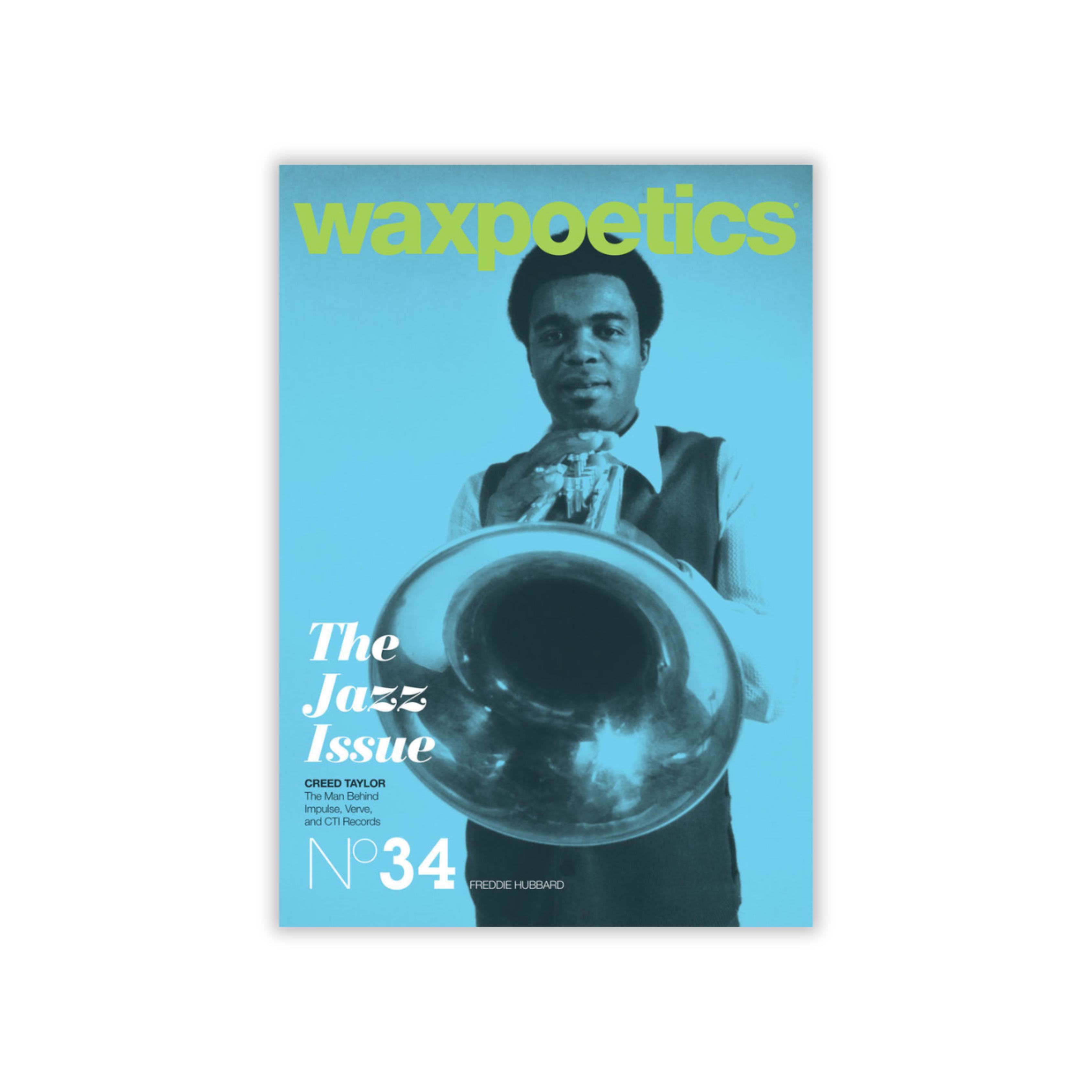

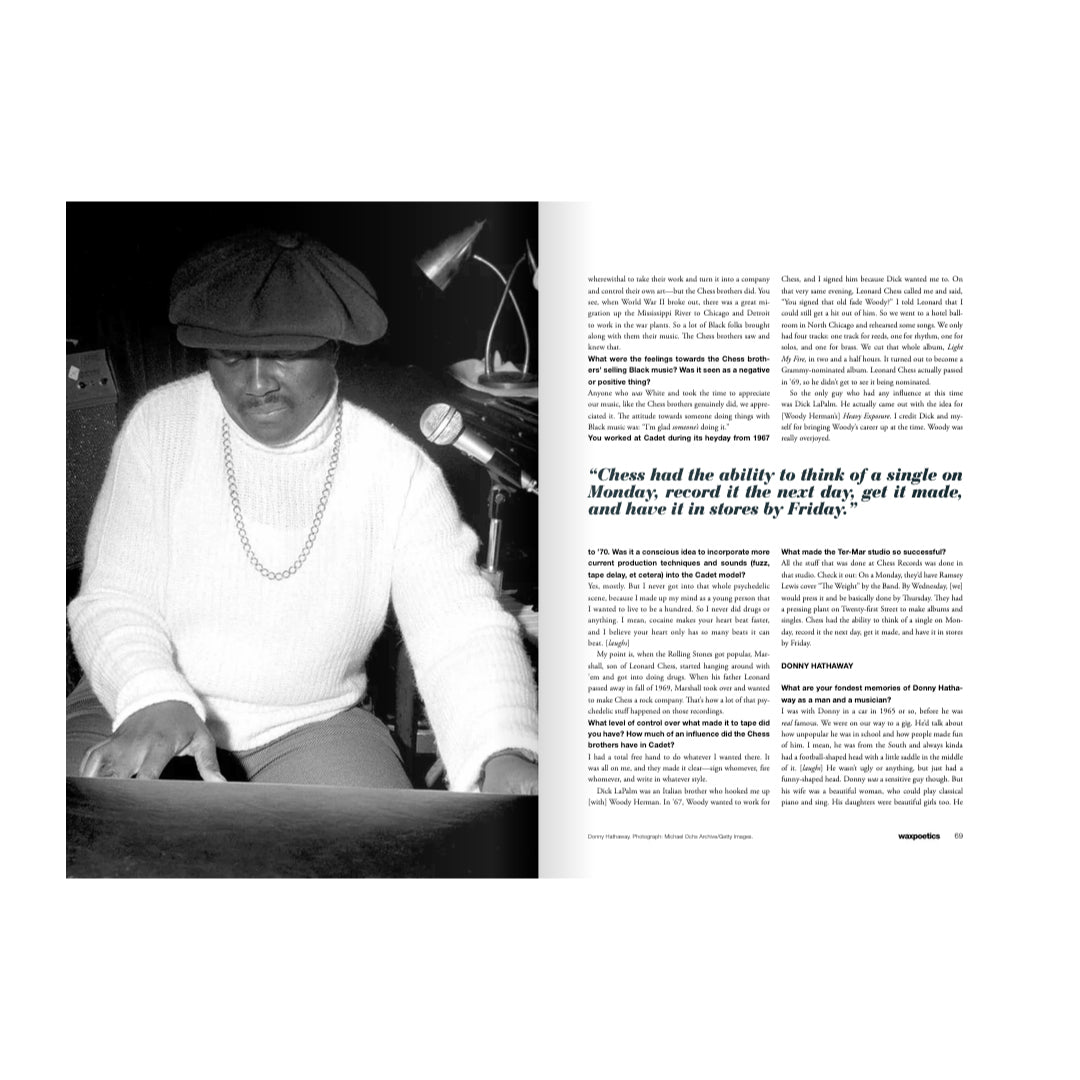

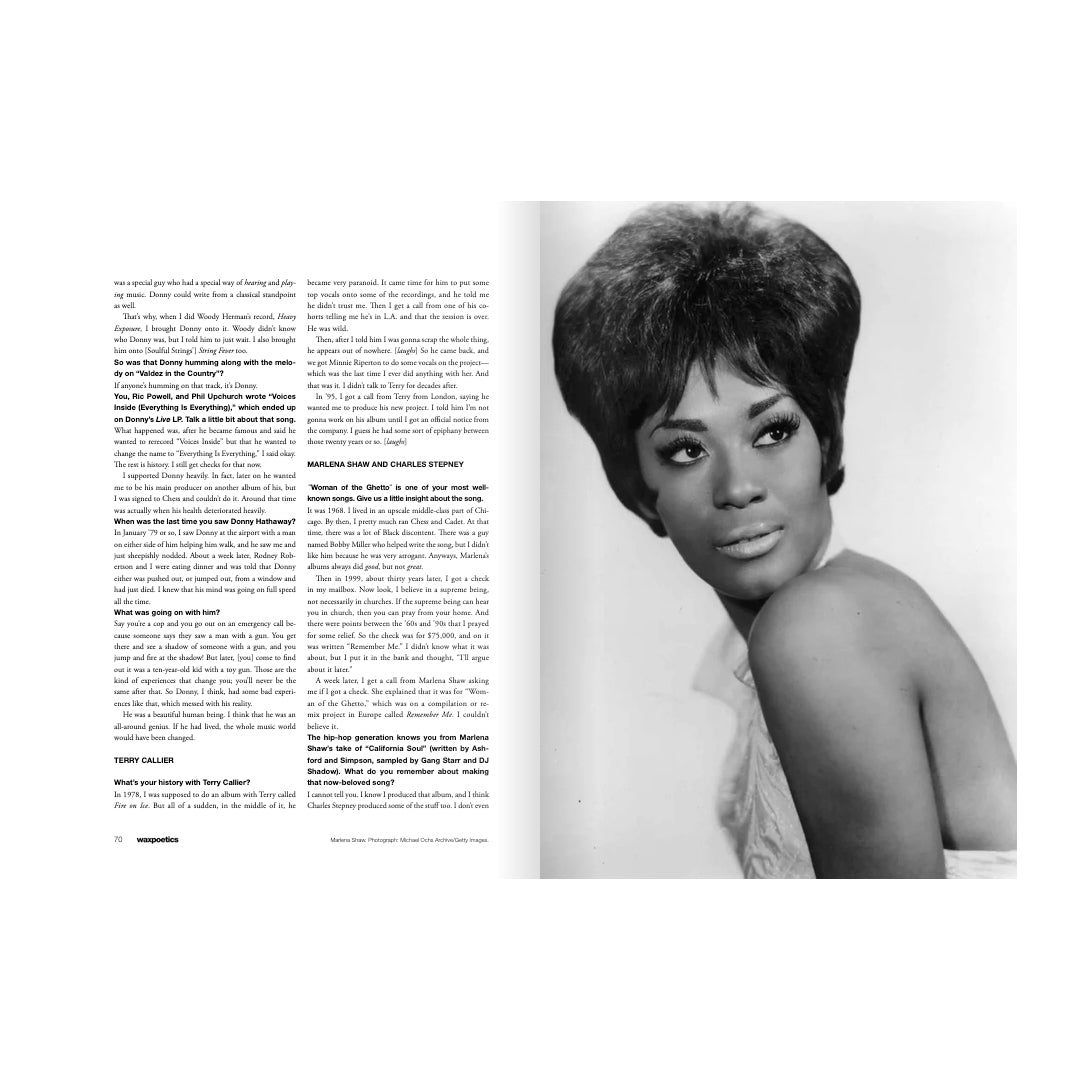

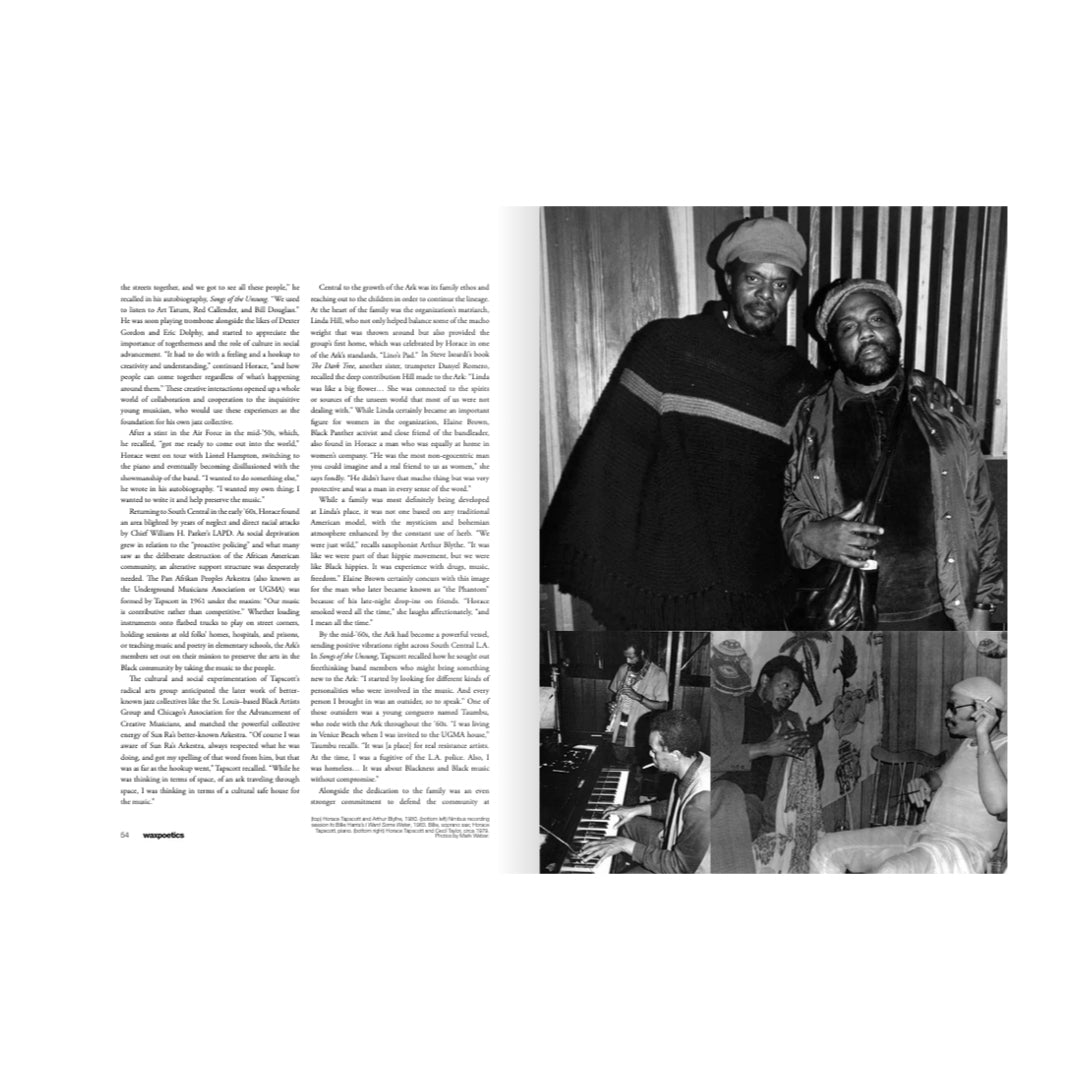

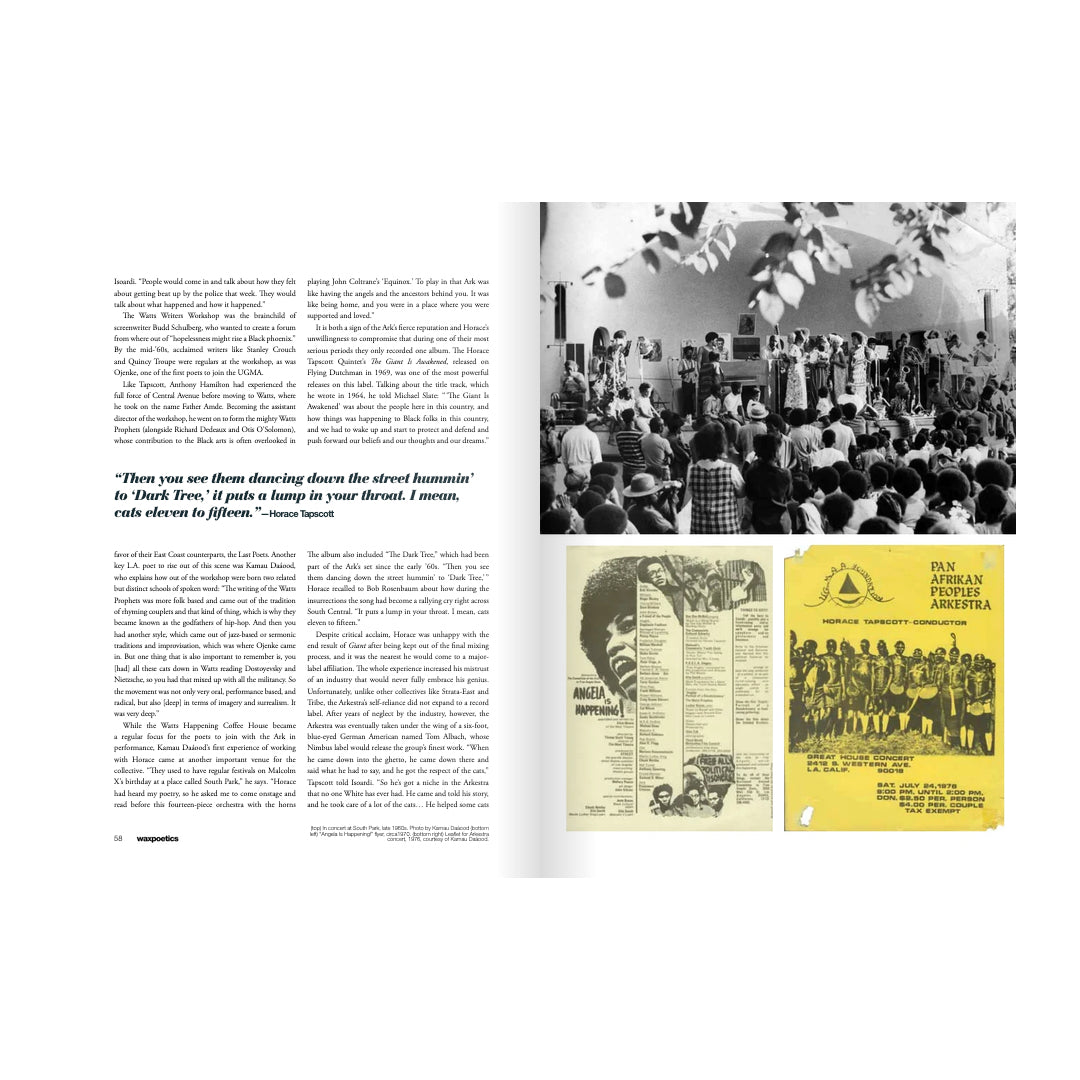

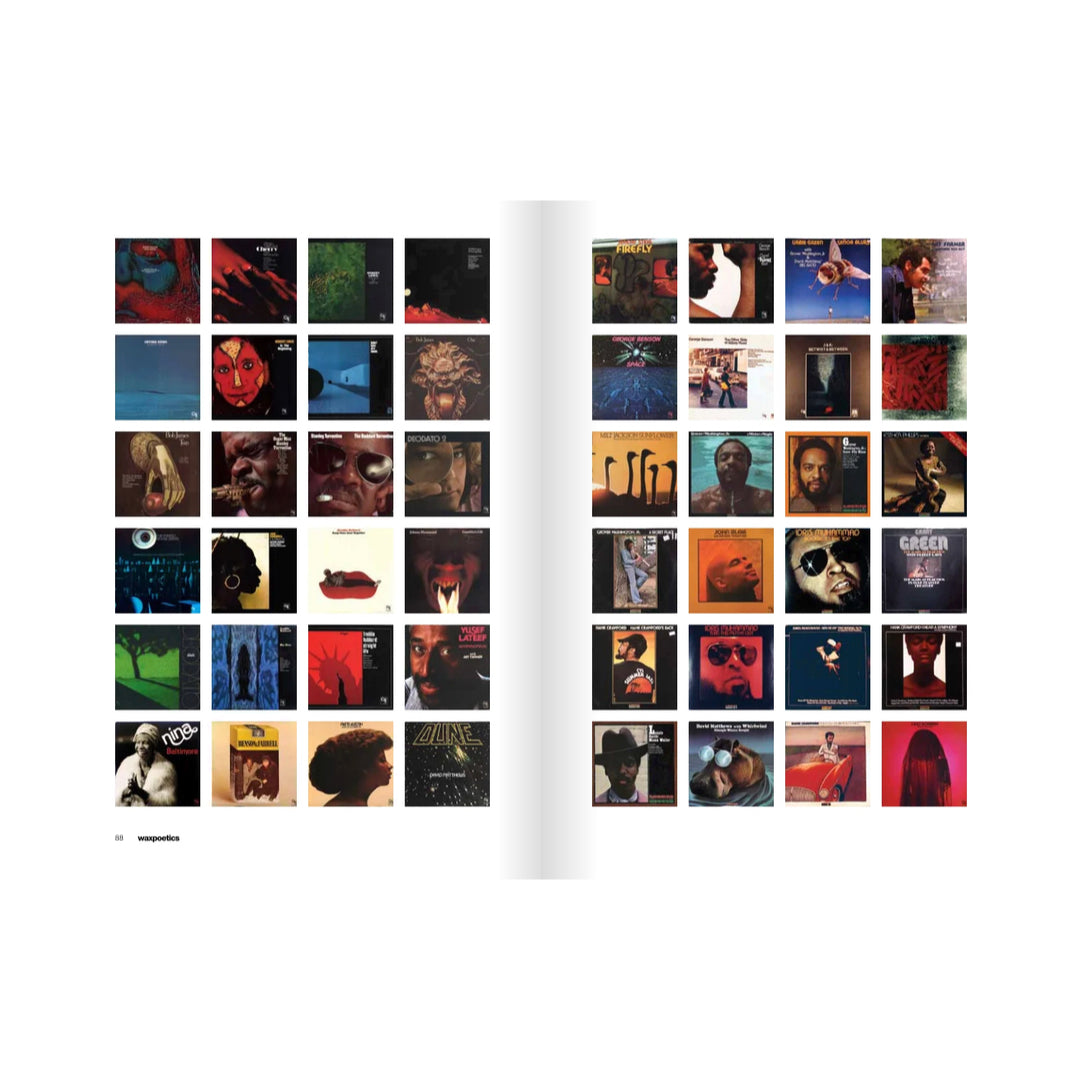

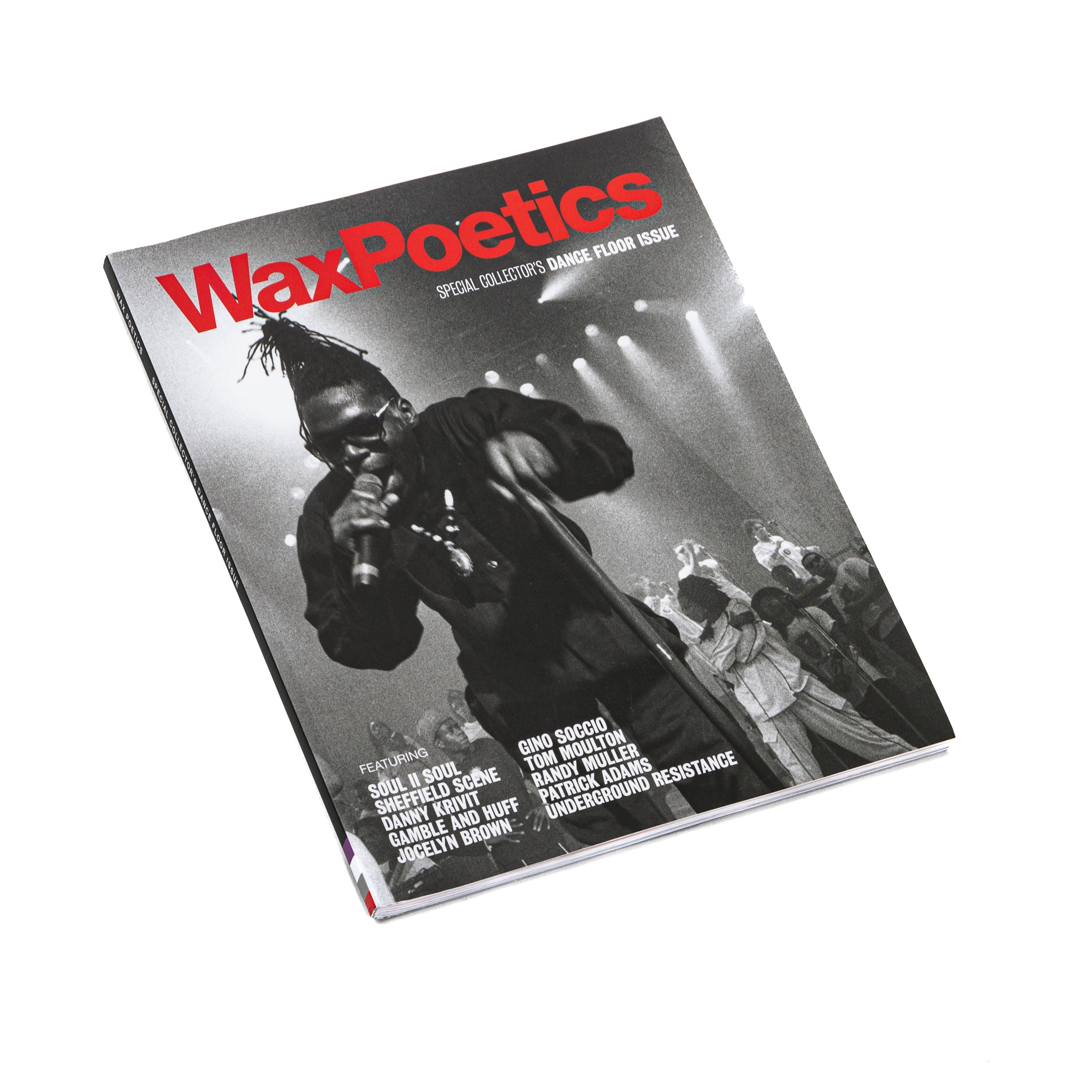

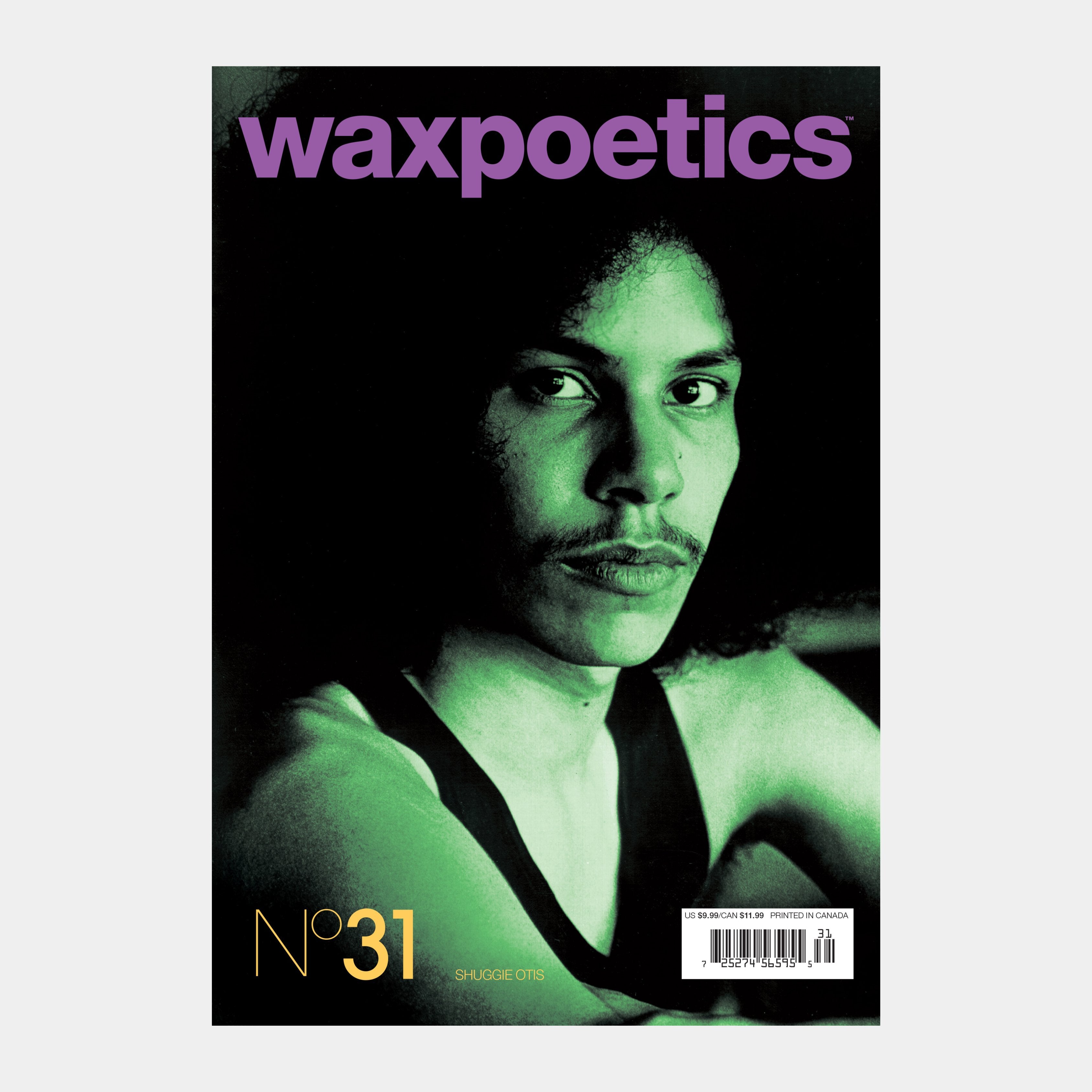

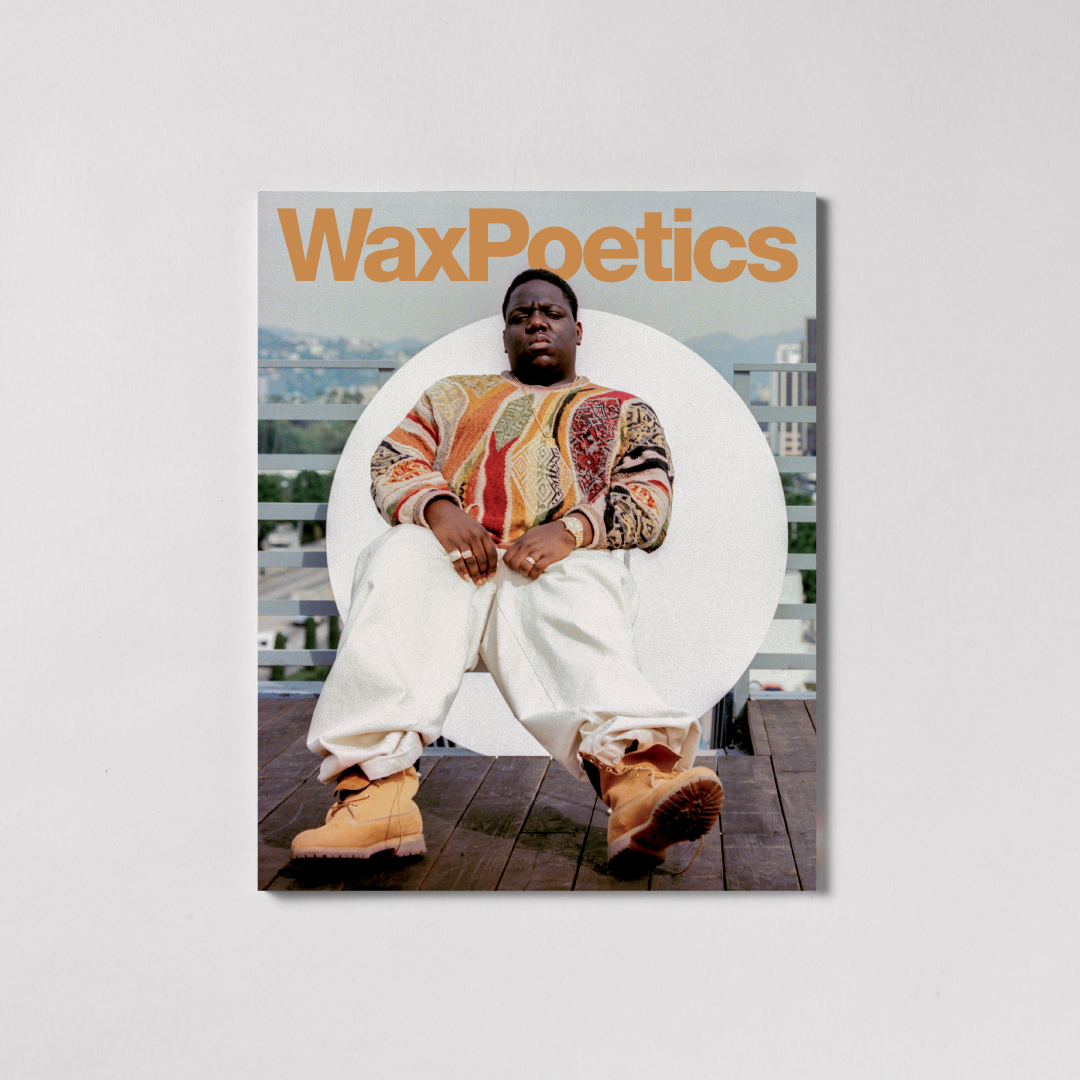

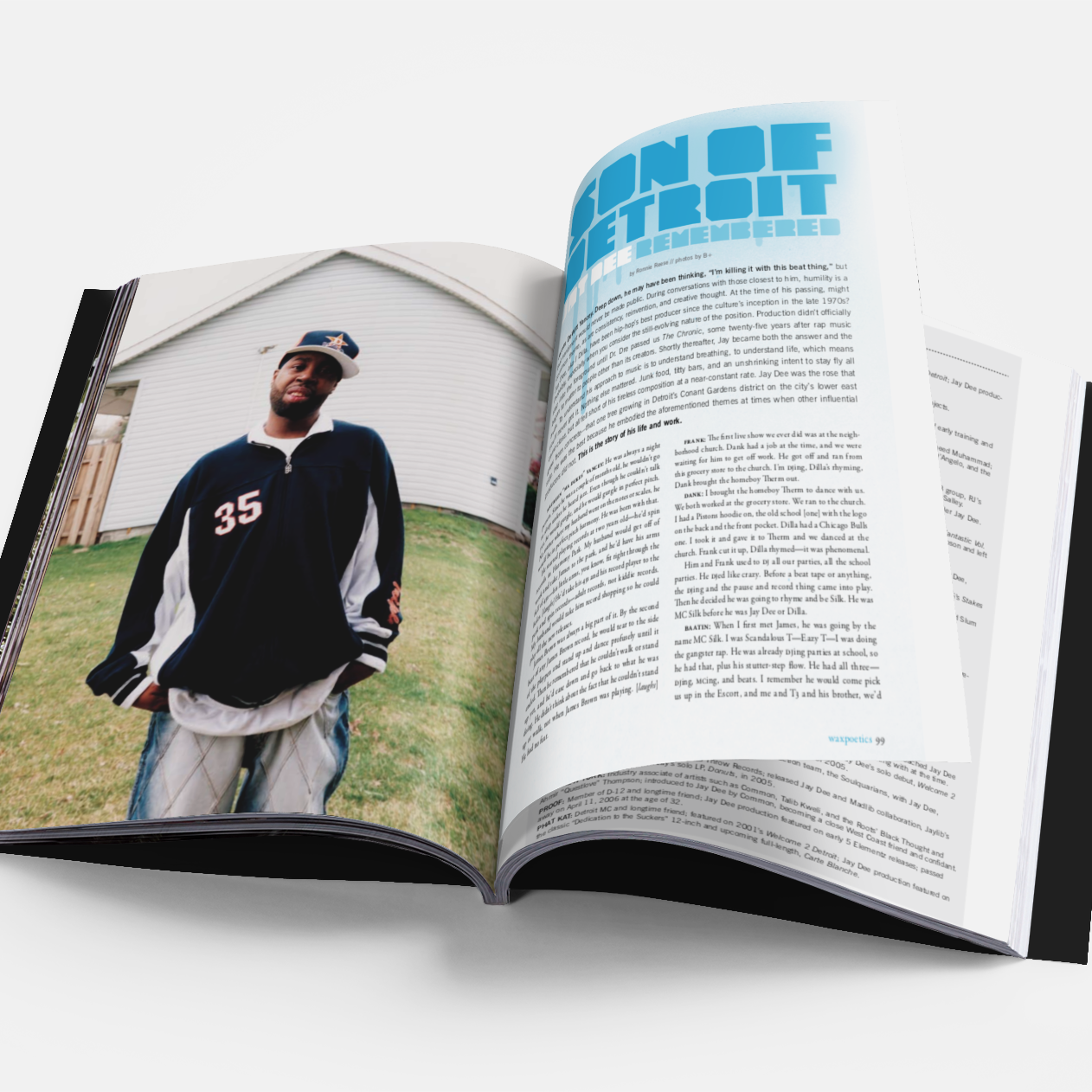

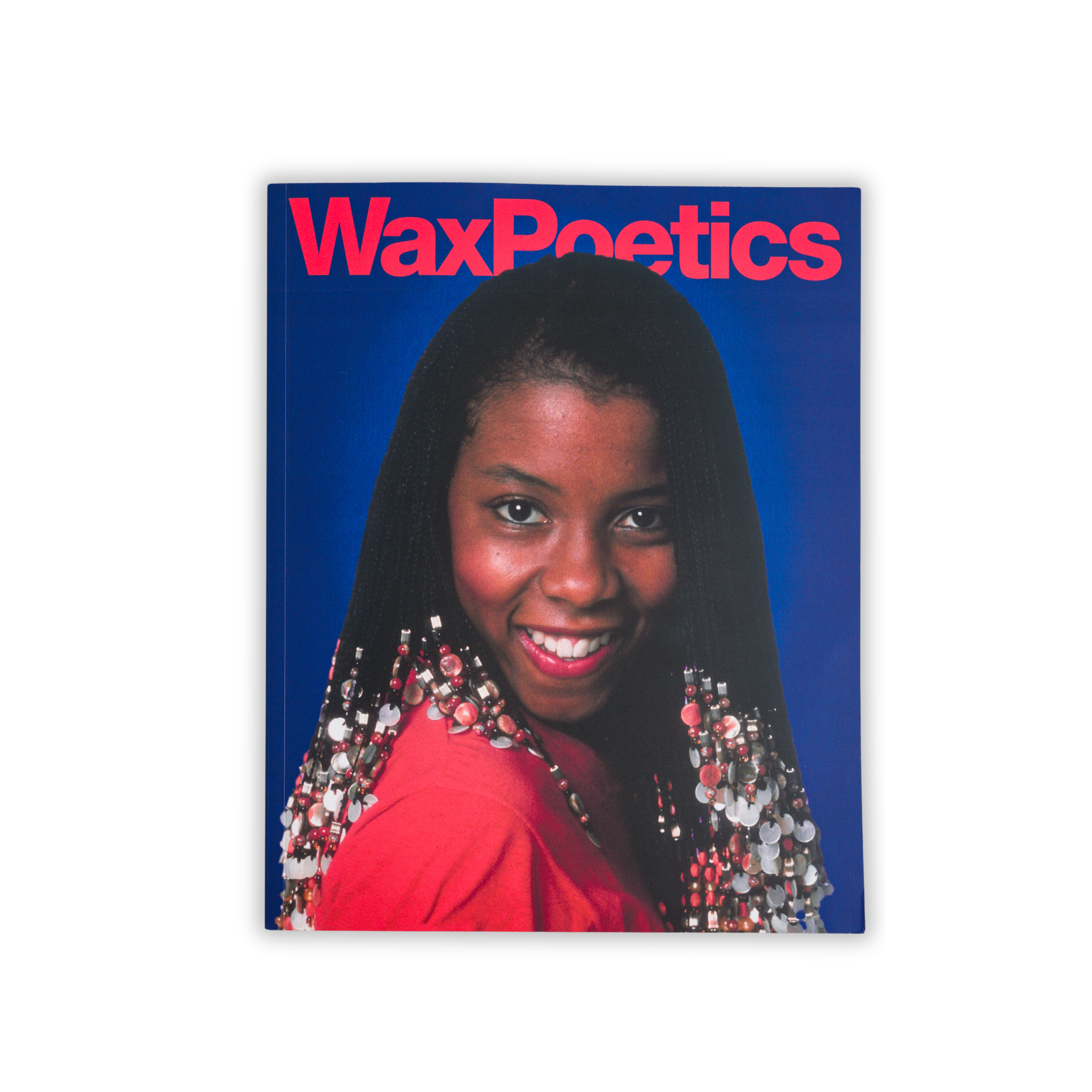

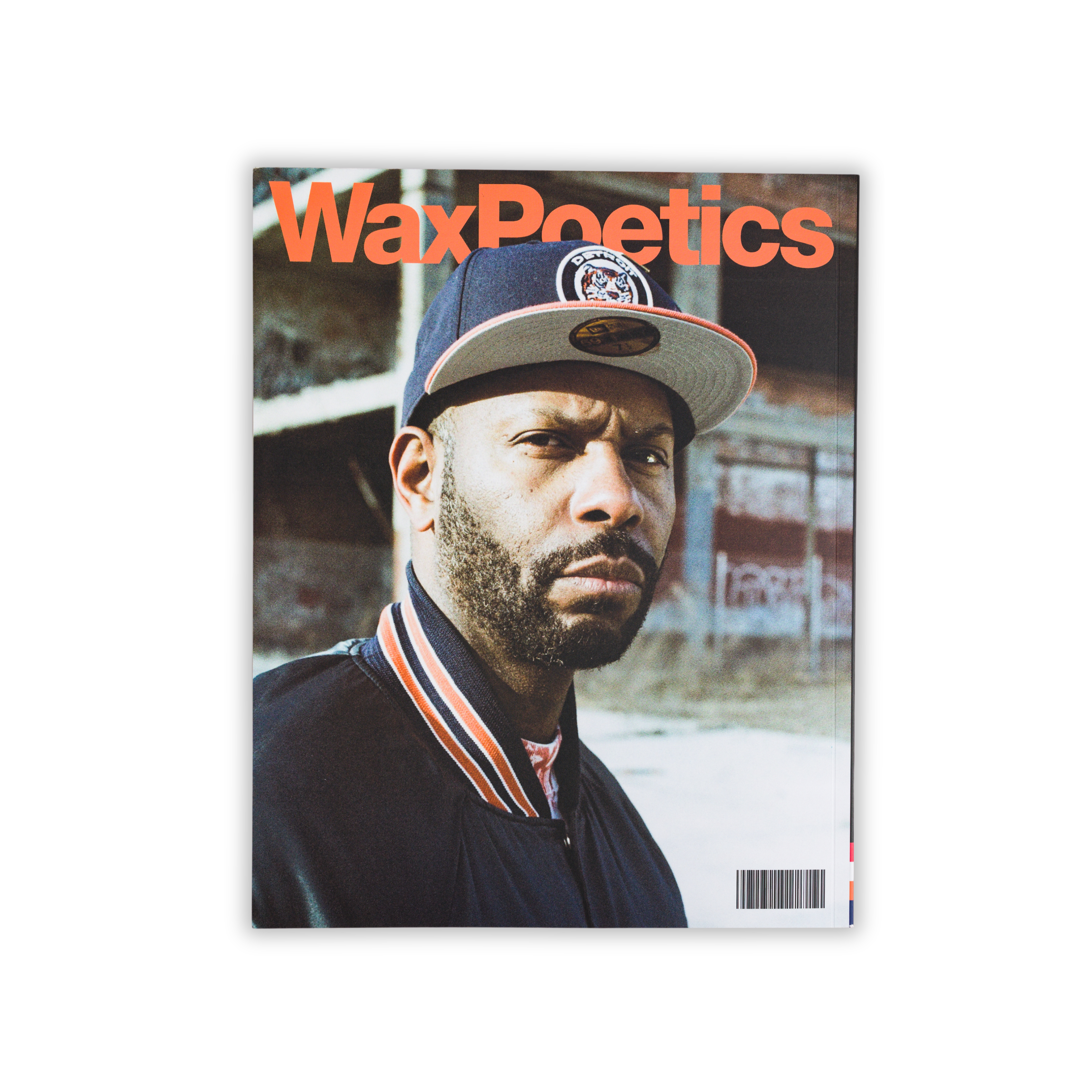

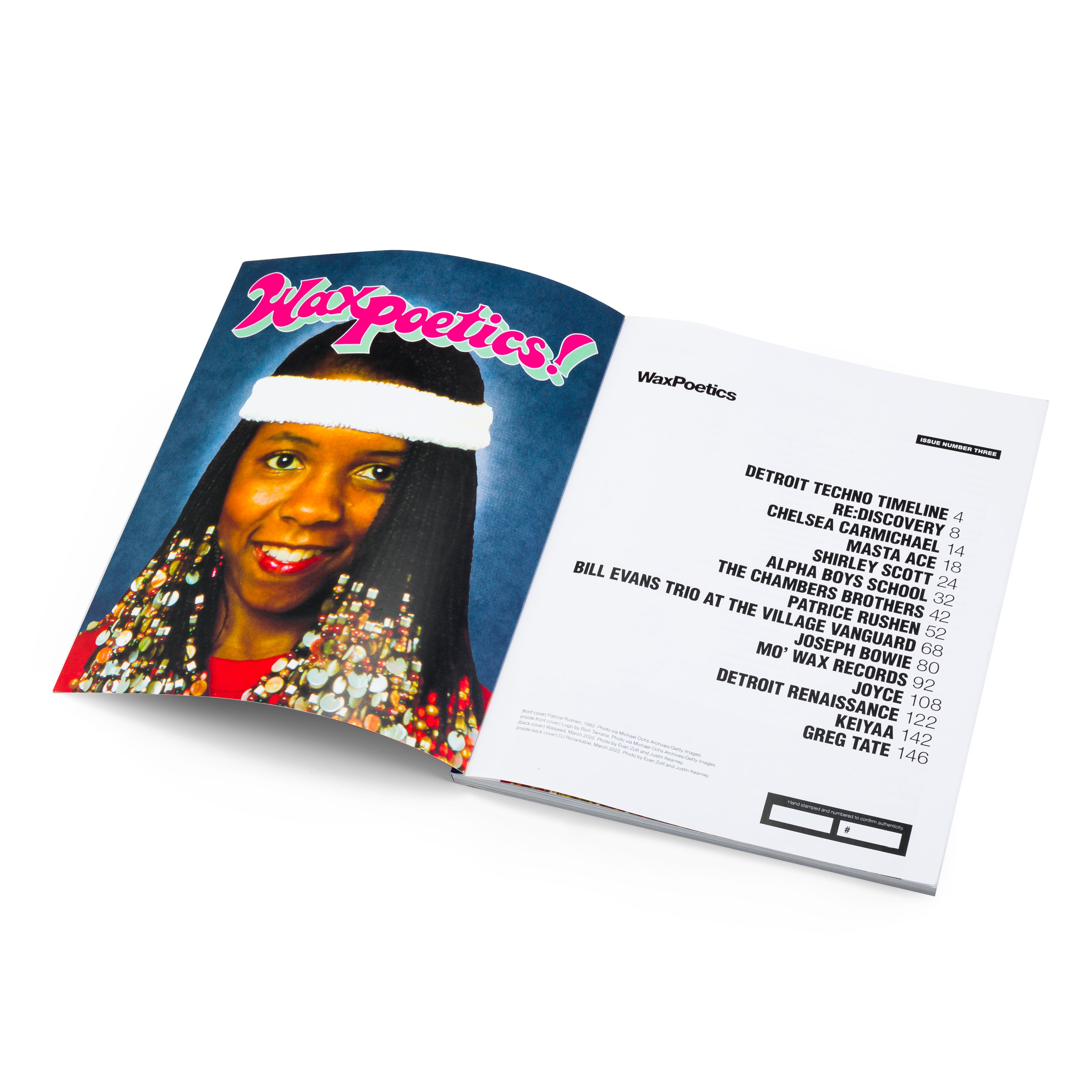

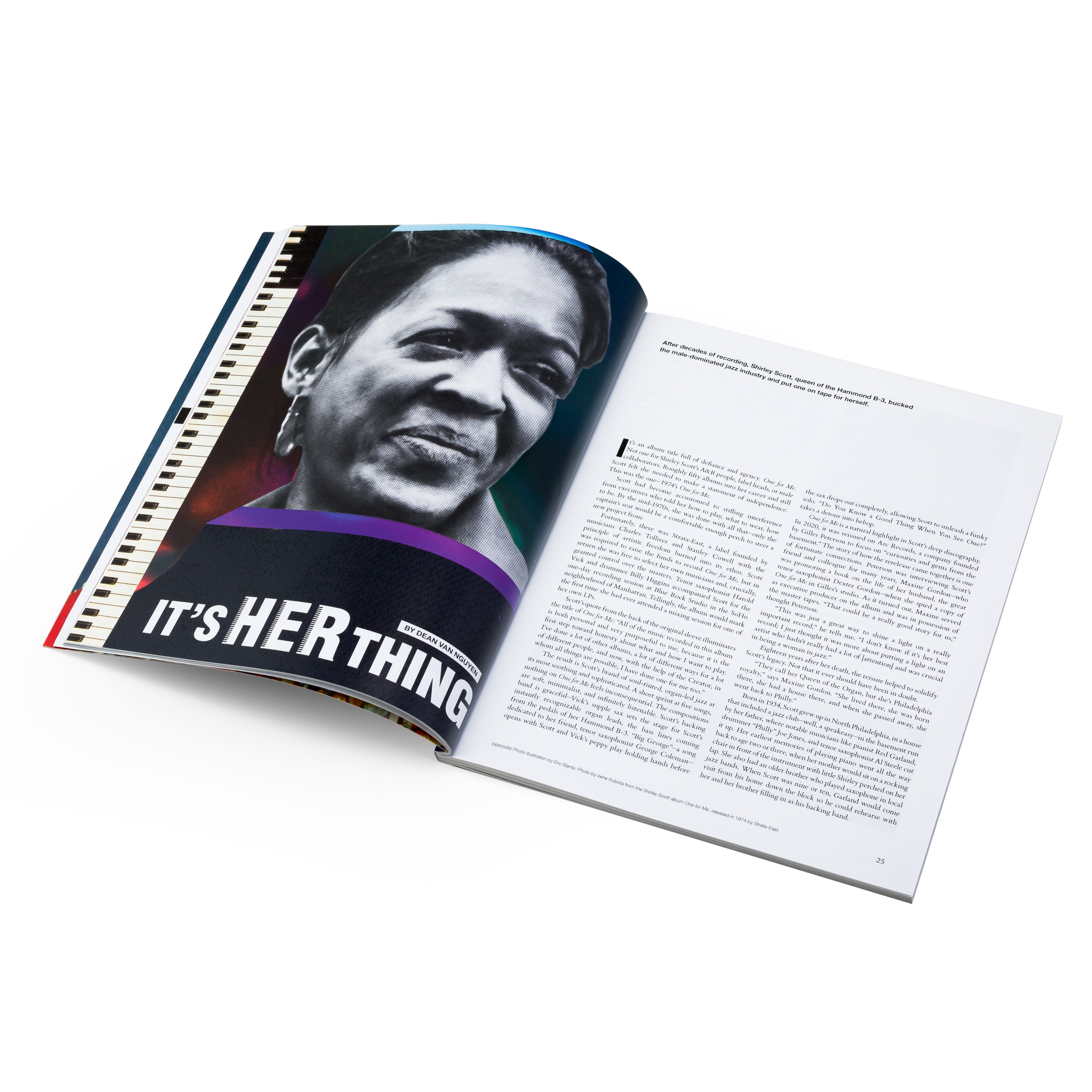

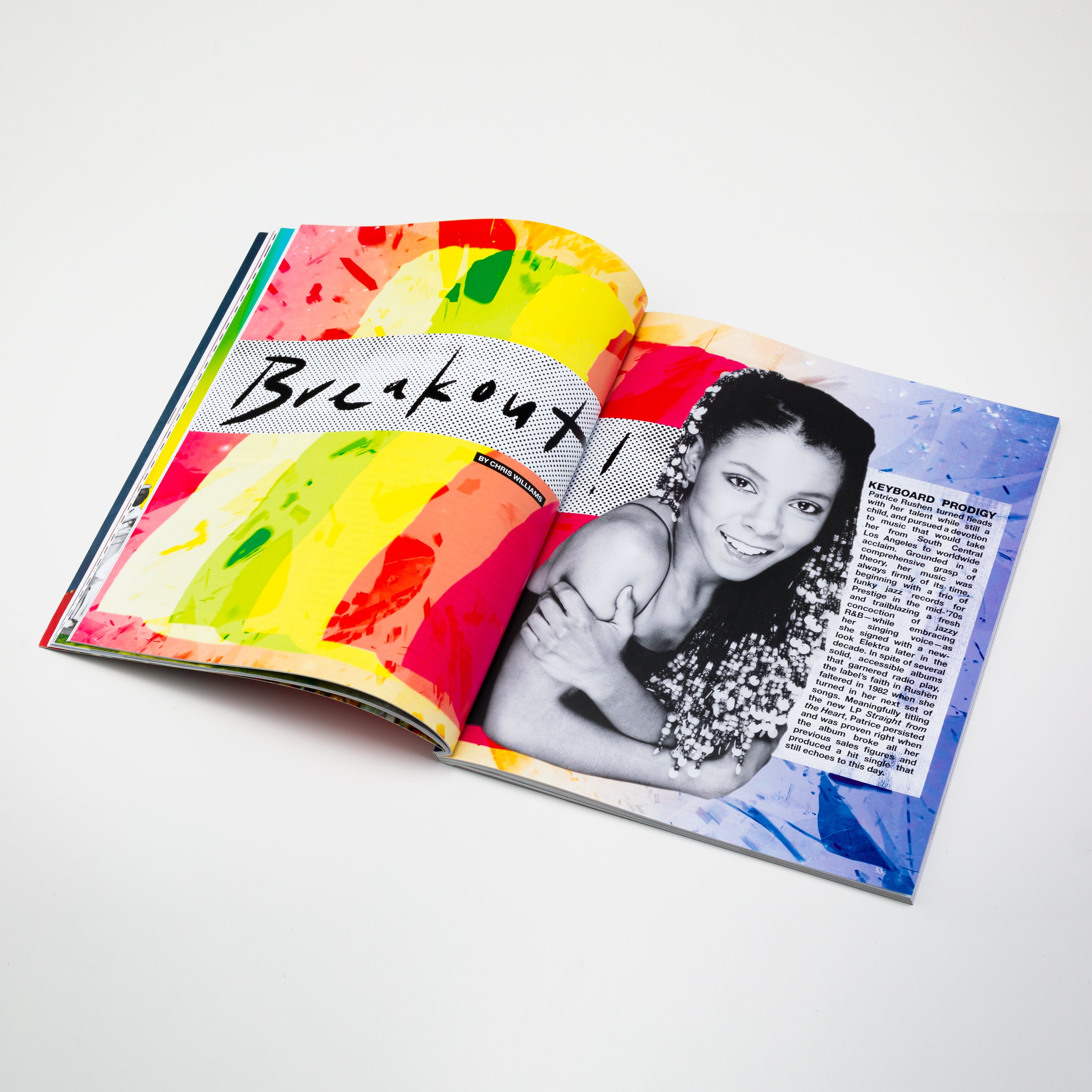

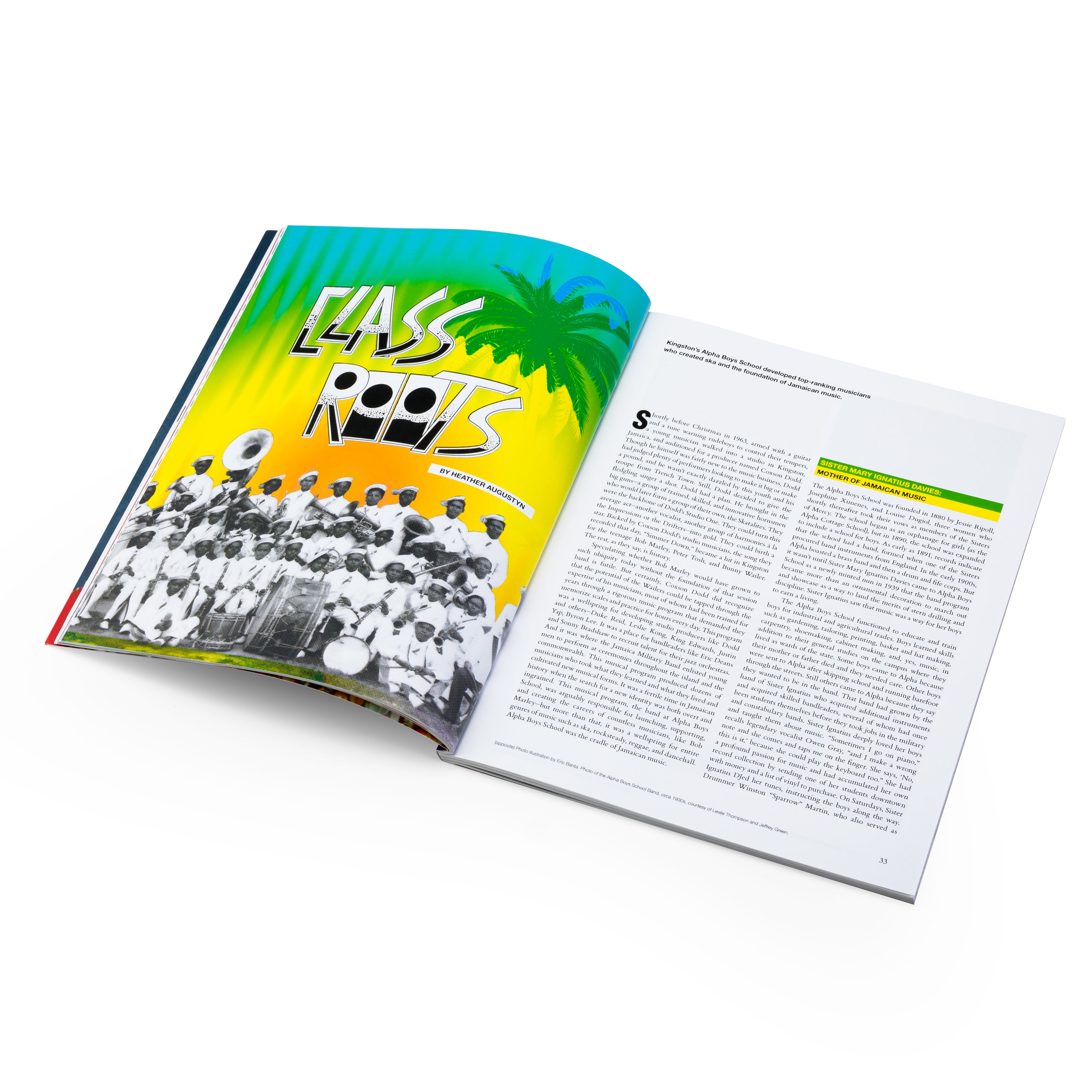

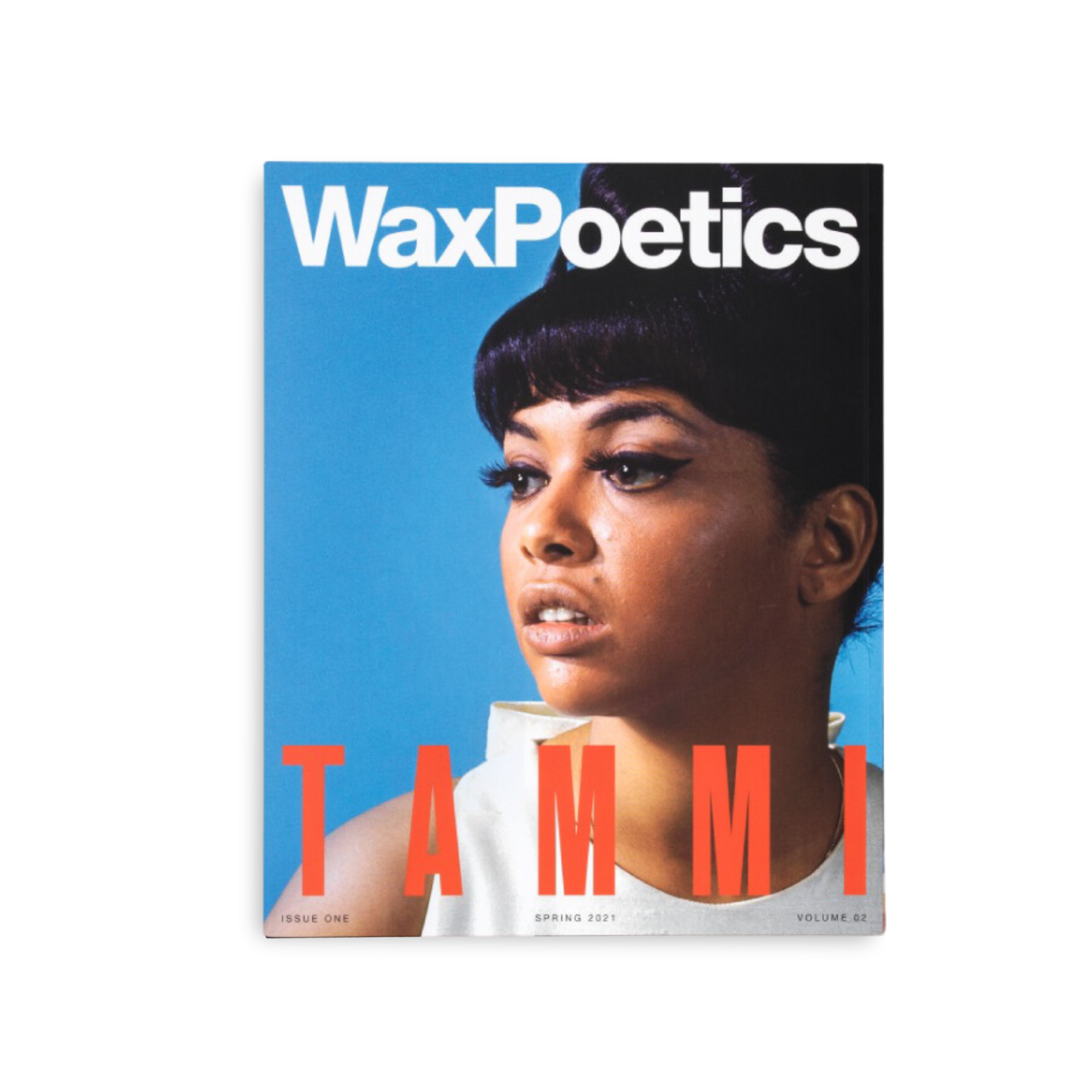

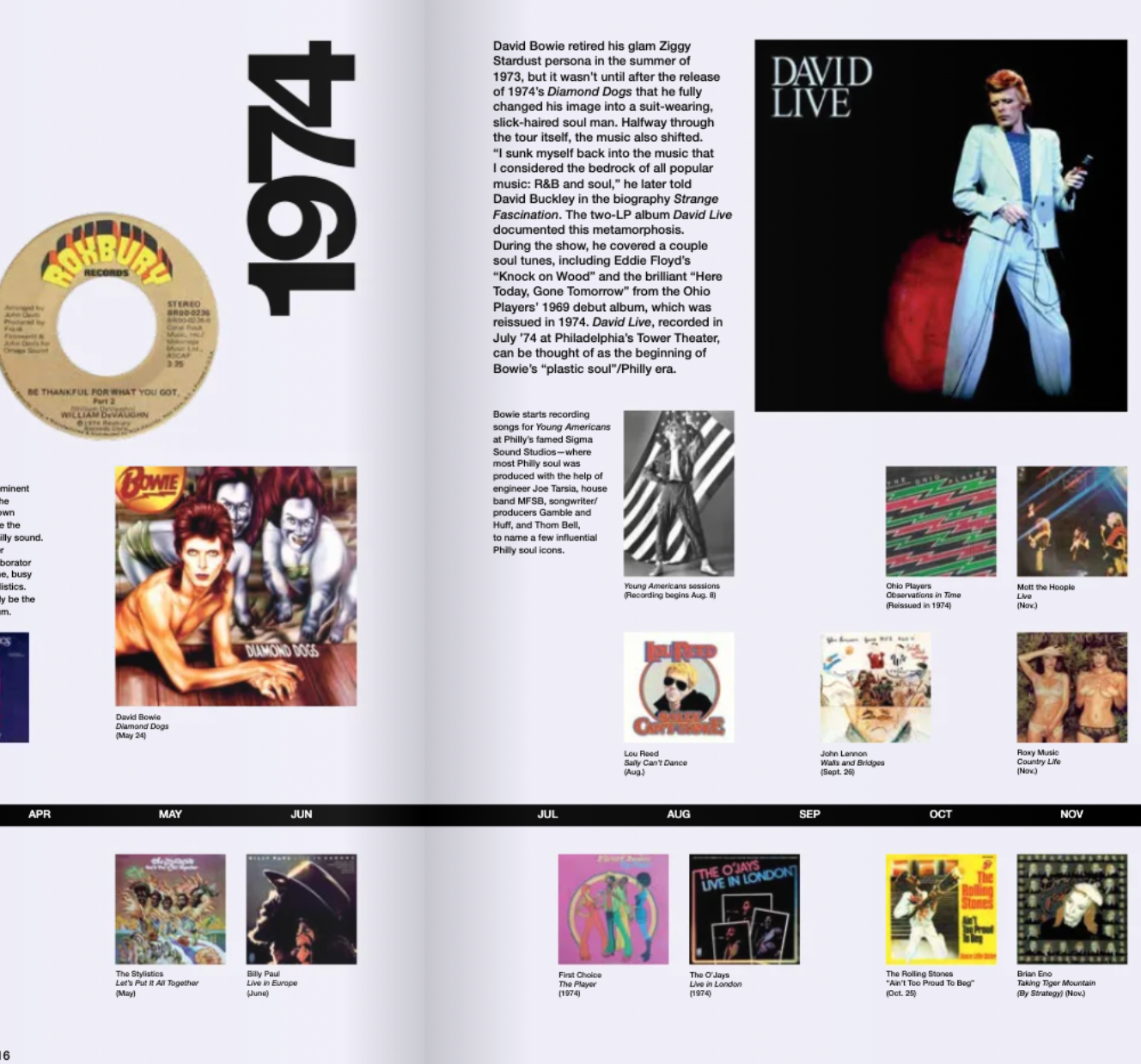

Wax Poetics Issue 5, Volume 2 - a 148-page journal that delves deep into Pharoah Sanders and Anri, Ron Trent, Dexter Wansel, Carolyn Crawford, Hyldon, Linda Lewis, Lance Ferguson, Psychic Mirrors, Liv.e, Bernard Wright plus Re:Discoveries, Record Rundowns and more...

Discover more music

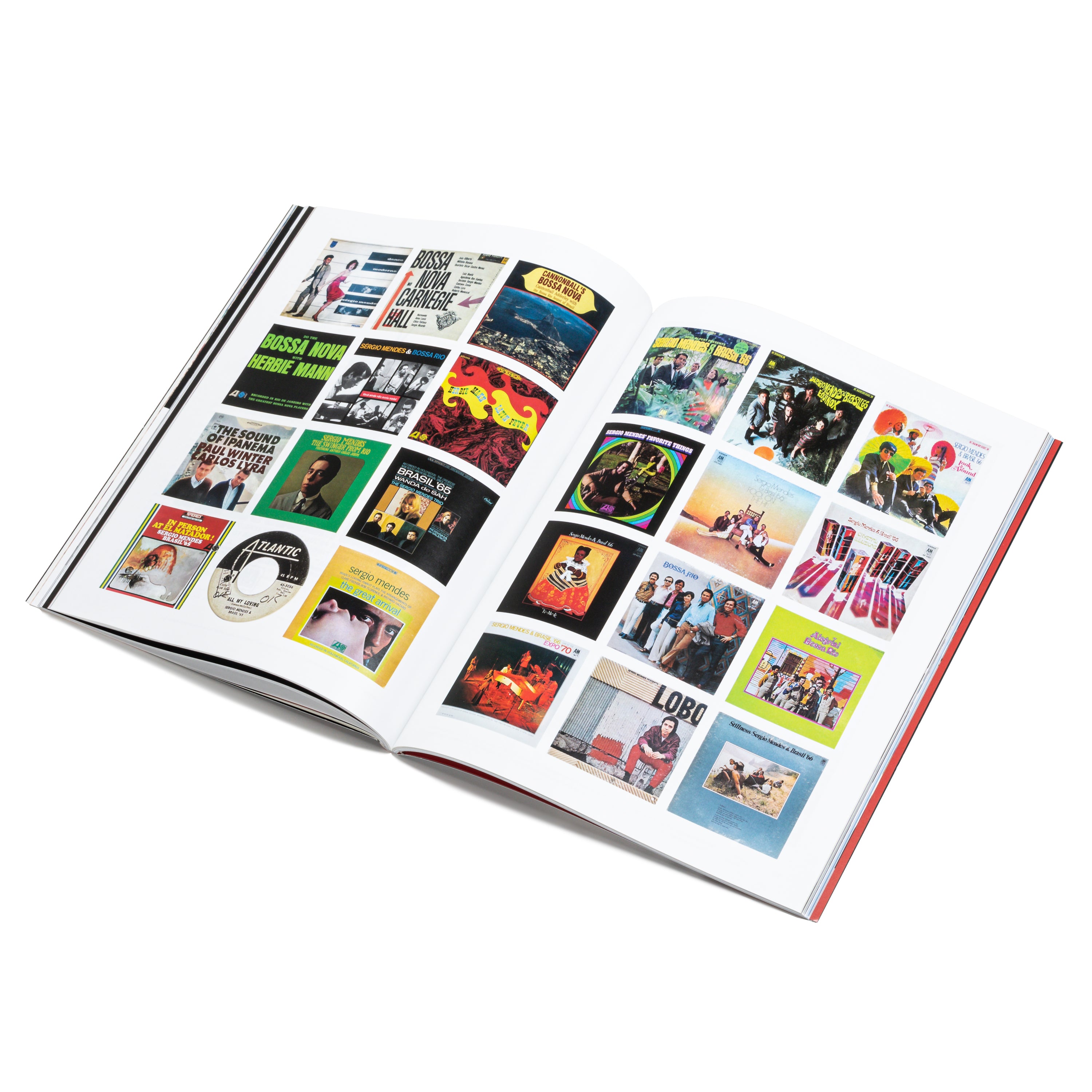

Each journal contains countless records for you to discover and collect.

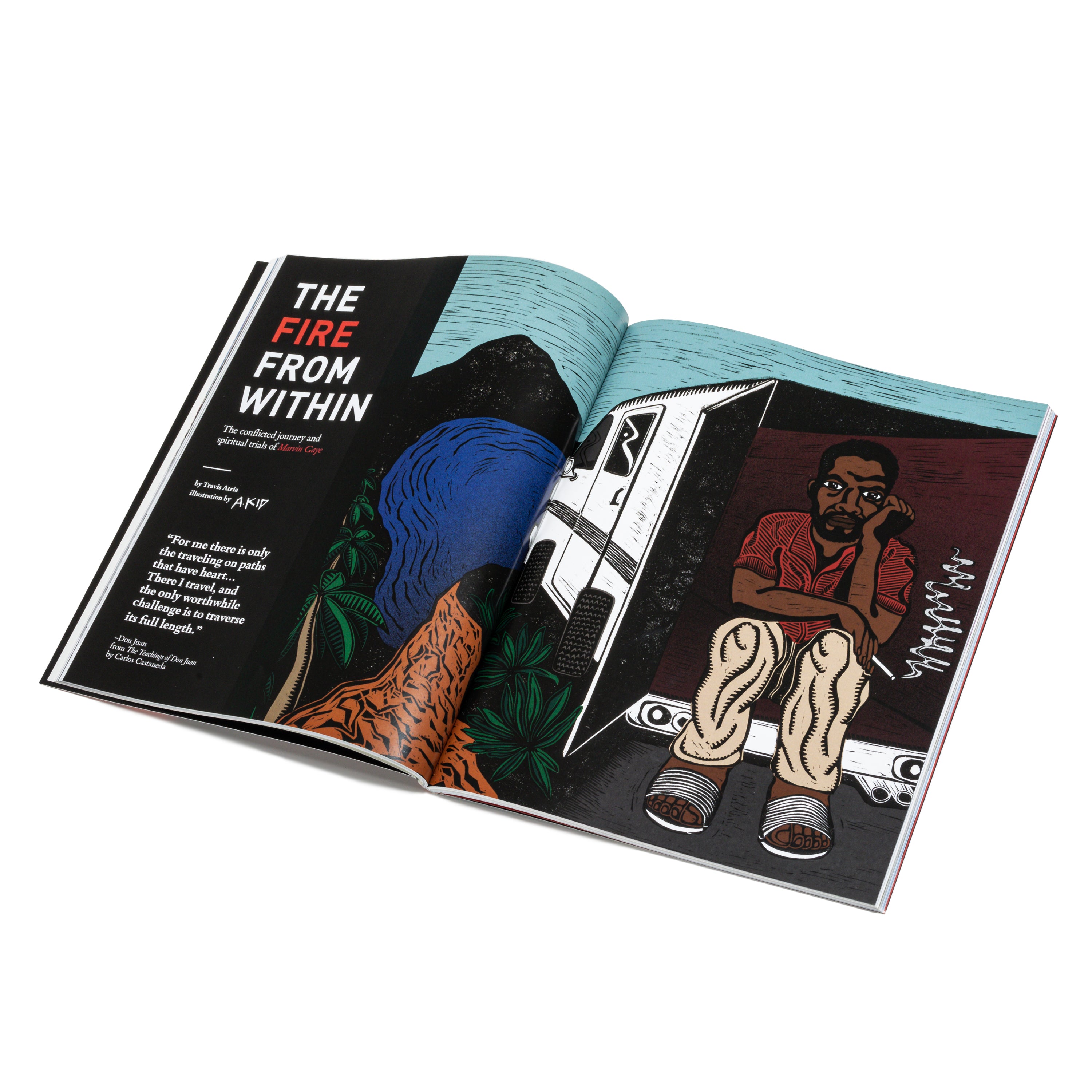

Discover the best stories

We go deep and help you discover more about the artists and scenes you love.

Build your music knowledge

Want to be the smartest person in the (music) room? Our journals will give you all you need.

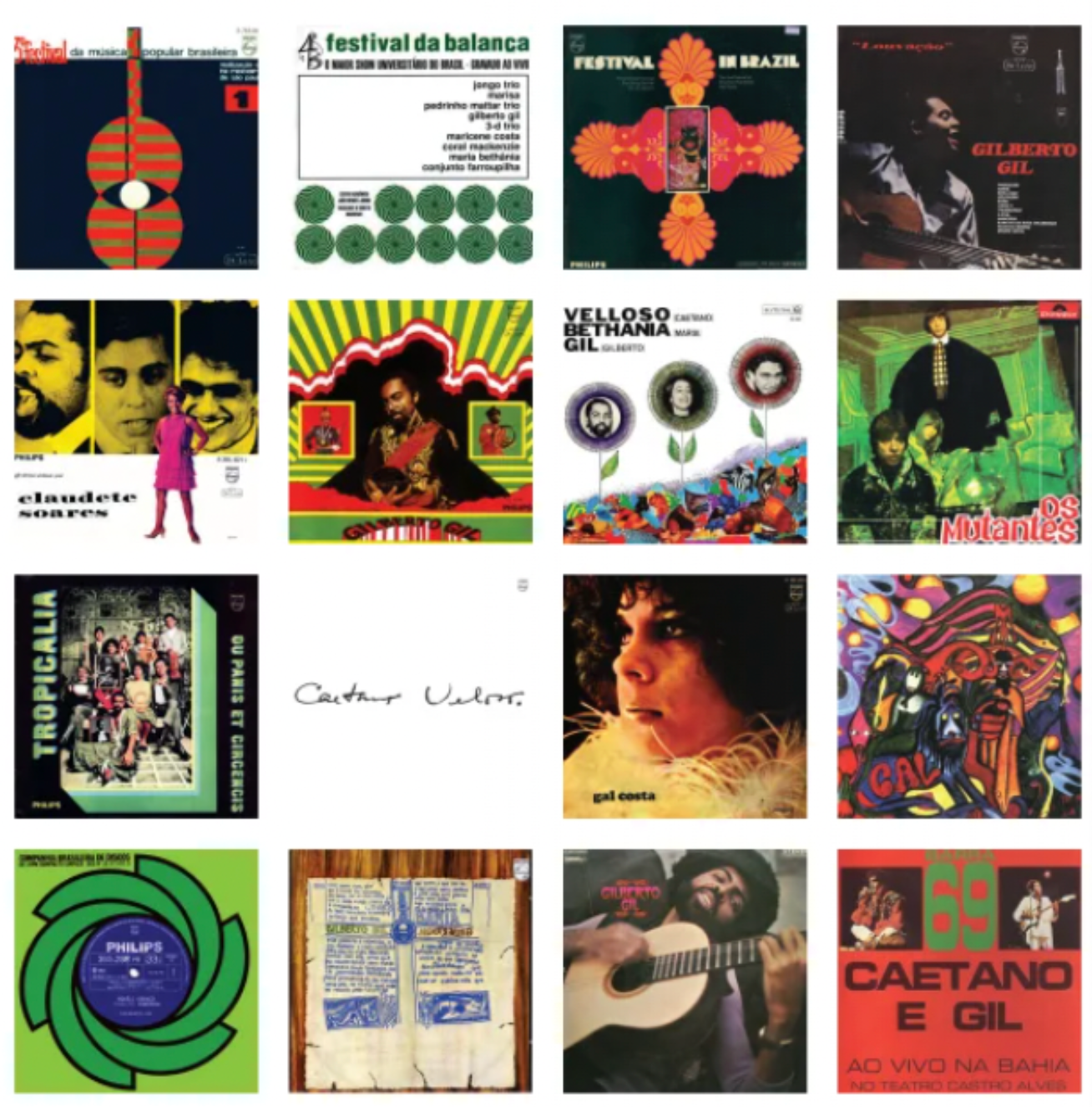

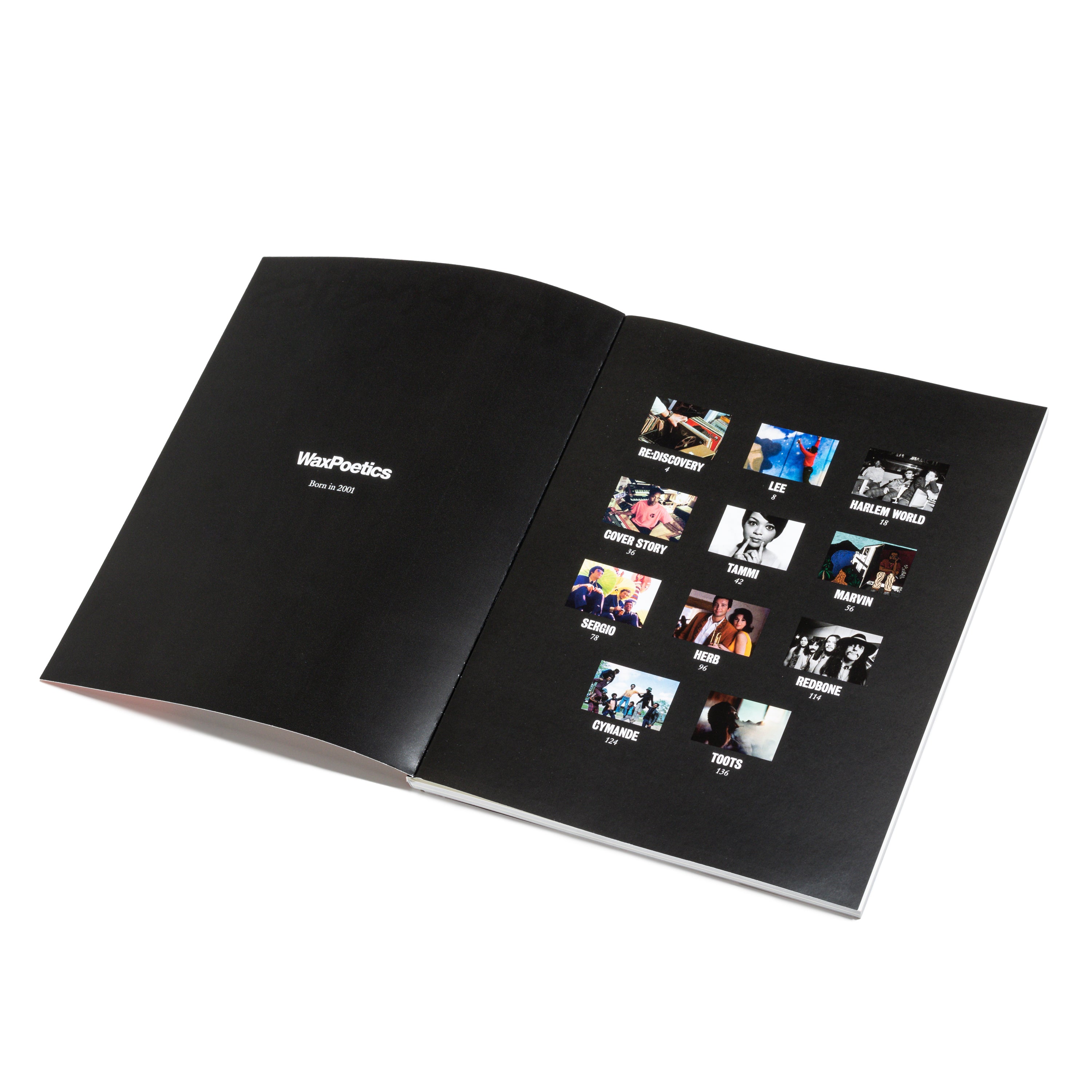

FEATURED IN THIS JOURNAL

Pharoah Sanders & Anri • Ron Trent • Dexter Wansel • Carolyn Crawford • Hyldon • Linda Lewis • Lance Ferguson • Psychic Mirrors • Liv.e • Bernard Wright

EDITORS LETTER

When we first started Wax Poetics in 2001, some called us imposters-we weren't real record heads! We laughed it off. We weren't trying to act like music experts. We considered ourselves entrepreneurs and publishers. But, honestly, I was just trying to be a real editor. And I was learning as I went. I never set out to be an editor. But I did have a crash course in college, years earlier, in countless creative-writing classes, where one must critique other writers. I learned to be constructive, to empathize with the writer, and, more importantly, with the subject. And I learned how to help other writers do their best. I got pretty good at it.

But a music expert? No, I was just an enthusiastic student. My first deep dive came in high school when a good friend introduced me to Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, Bill Evans, Dave Brubeck, and Paul Desmond. I can still remember, at sixteen, when we drove through the South Dakota Badlands at night, lost in the pitch-black, searching for civilization, while listening to "Forty Days" over and over.

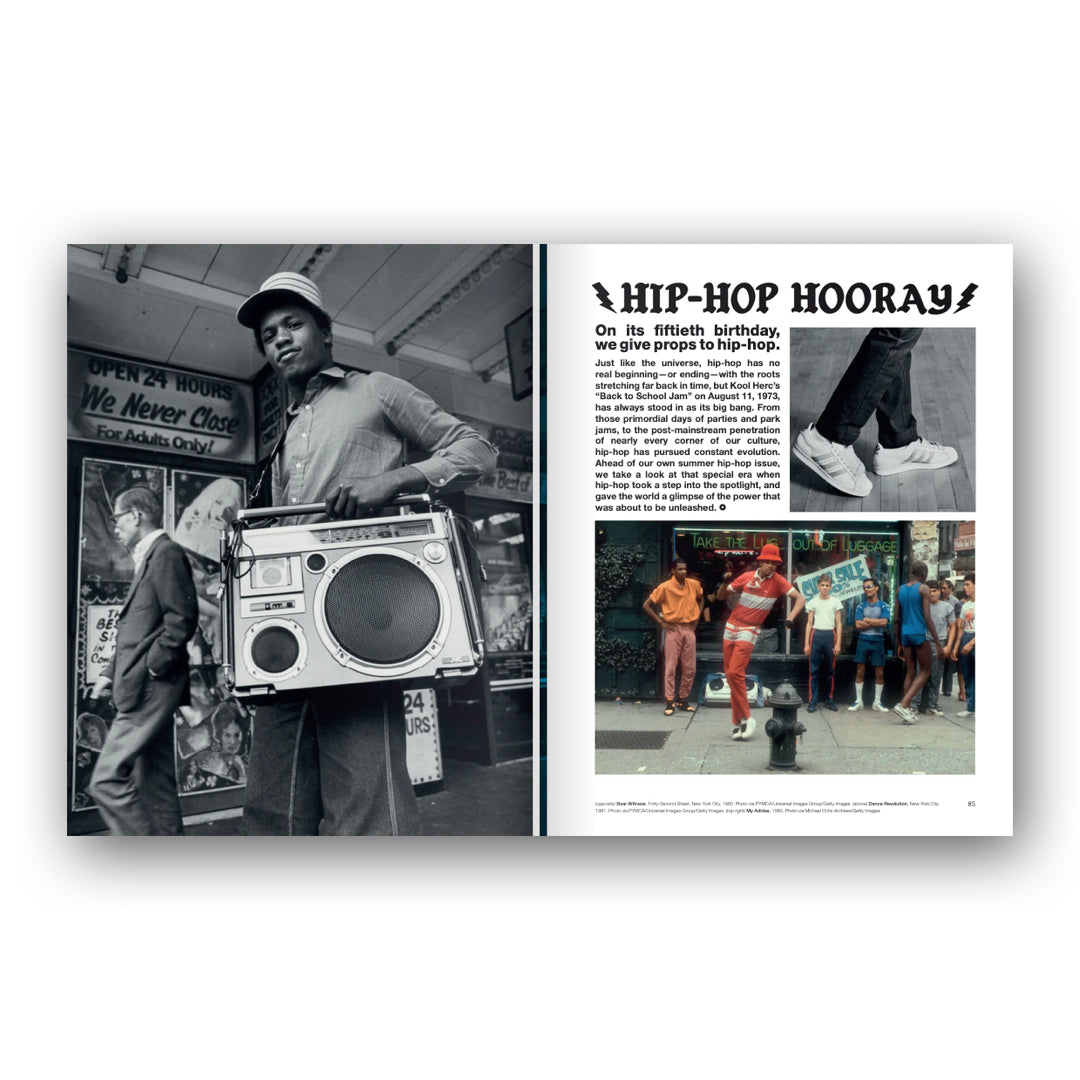

In college, around 1992, I discovered the CTI reissues that Columbia had started releasing on CD a few years earlier. What a revelation. And then, around the same time, came a hip-hop wave. I had grown up listening to Run-DMC, Beastie Boys, and, later, De La Soul, but as 1993 rolled around, my mindscape expanded. Souls of Mischief, Digable Planets, Ice Cube, A Tribe Called Quest, Gang Starr, Pharcyde, Wu-Tang And then I put a pair of Technics 1200s on my first credit card. That was it. Saving money, being a normal adult-all of that was gone forever. But the hip-hop obsession drove my love of jazz deeper. The first record I bought at that time was a used copy of Donald Byrd's Fancy Free-still in rotation. And when I started chasing samples, my mind melted. "93 "Til Infinity" led me to Billy Cobham's "Heather," a good song to start the day with.

After college, in 1996, I moved to Brooklyn with the idea of chasing a hip-hop fever dream, or writing the great (and weird) American novel-trust me, that sounds just as crazy to me. When I arrived that winter, a mixture of snow and mud covered the sidewalks, and Ol' Dirty's "Brooklyn Zoo" and "Shimmy Shimmy Ya" seemed to blare from every radio and passing car; Wu was everywhere. It was a special time to be alive. I became a bona fide hip-hop head fast. I started amassing a huge collection of hip-hop albums and singles, spending all my money at Beat Street at Fulton Mall, just down the street from my apartment, or Fat Beats on Sixth Avenue in the West Village. I can recall passing the famous West Fourth Street basketball courts on the way from the subway on one of those rare New York spring days where the air is still filled with hope.

My curiosity about sampling grew. I printed the entire Rap Sample FAQ website and put it in a binder, studying it day and night. I scoured Academy Records dollar bins, and traveled up and down Manhattan, going to record stores now long shuttered, searching for impossibly rare records that I never found. But it was all about the search. I didn't know where I was going, but I loved the journey.

Those memories are like dreams now - foggy and fleeting, almost unknowable. Which makes the present more extant. Like hip-hop itself, I turn fifty this year. I'm not the young man I was when we started this journey. At the turn of the century, my now wife and I rented a cargo van, loaded up three cats in a converted refrigerator box, my turntables, a couple vintage Lane mid-century side tables, and crates and crates of records, and drove cross-country to California

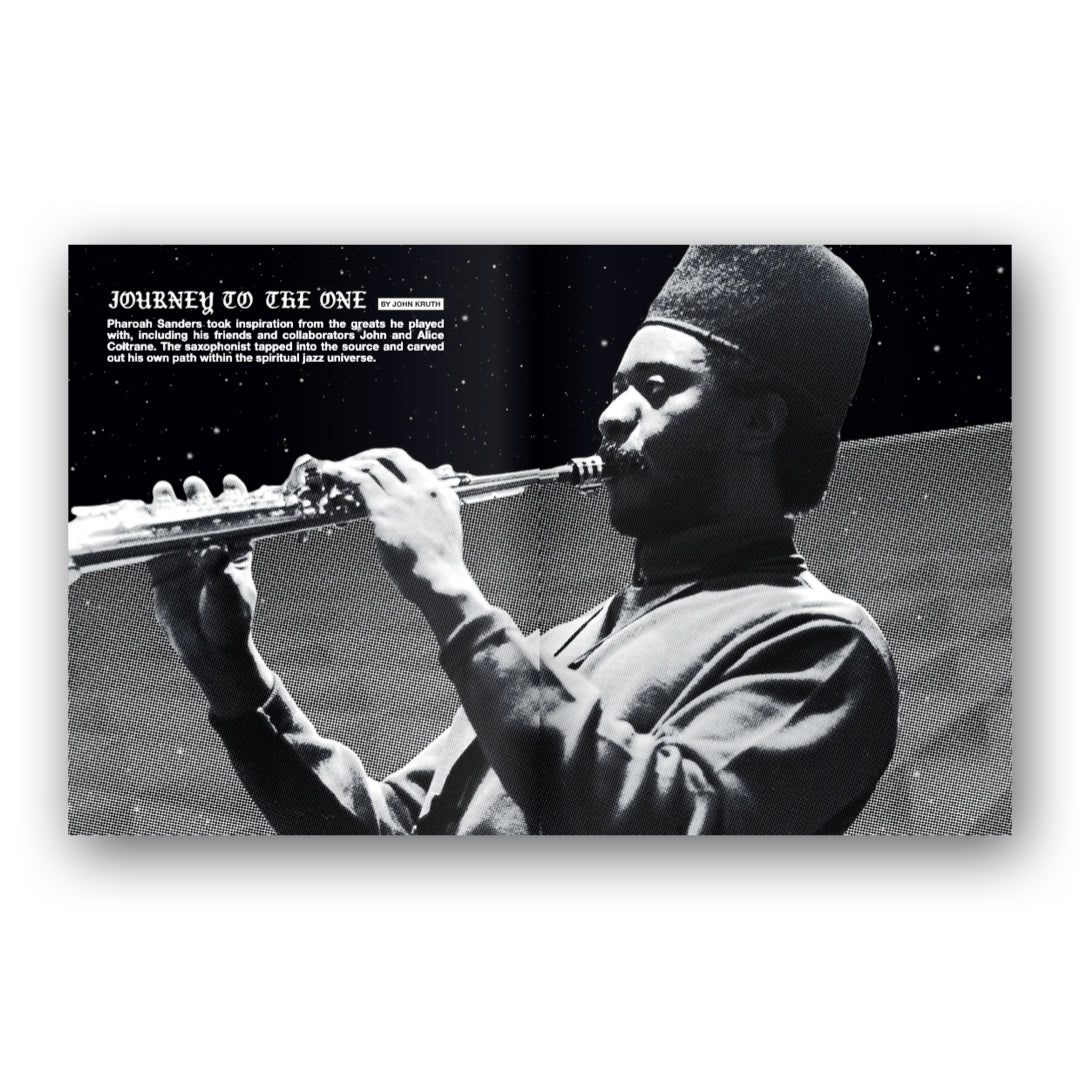

At the time, it seemed like a good idea to start a music magazine (not my idea!). There wasn't much around that explored hip-hop's roots through sampling. I had been reading the humble British mag Big Daddy. I was pretty familiar with London's acid-jazz scene, but here I was introduced to Gilles Peterson...and something called jazz dance? DJs spun jazz and got the dance floor poppin'? My younger self was incredulous of all of this. One song that was played for the dancers was Pharoah Sanders's "You've Got to Have Freedom," from his 1980 album Journey to the One. I was familiar with Pharoah, mostly his more accessible tracks like "Thembi," "Astral Traveling," and "The Creator Has a Master Plan," and especially his work with Alice Coltrane-and had even seen him play live at the Knitting Factory in New York; but I'd never heard of this record. There was no Google, no YouTube, no blogs. I searched for the album in record stores-fruitlessly. When a friend who sold records (but not this record) played me the song, I finally understood. There was a transcendence to it. There was this familiar feeling of a search for higher meaning, for wisdom. It was a call to freedom and peace.

Pharoah's friend John Coltrane was a musical hero of mine. I collected even his most challenging albums, ones he recorded at the end of his too-brief life. He wasn't making records for other people to listen to. He was searching for something. He was on a journey that went beyond music. Those records are difficult, as is most avant-garde music. In New York, I saw a lot of live jazz, and especially free jazz. It was at the Vision Festival in the Lower East Side, in an old synagogue on Houston Street, where I had a near-spiritual revelation. I went despite having a fever (this was 1997!), and while watching saxophonist David Ware play with pianist Matthew Shipp, drummer Susie Ibarra, and bass icon William Parker, I entered another state of consciousness (partially thanks to my high temperature). I realized this music was not meant to be listened to on a recording; it was meant to be witnessed live, as it goes beyond music-it's a sort of searching.

And that's why Pharoah Sanders continued to perform until his final days. Always searching, always on the journey. And the journey is what kept me doing this for twenty-plus years. I learned a tremendous amount. I made friends (and enemies)-and art. While it's not what I originally set out to do, I've been lucky to be involved with a creative pursuit all these years. I'm forever grateful to everyone who has helped keep this journey going. In our Pharoah cover story is a quote that struck me. ESP-Disk founder Bernard Stollman, when looking back on his legacy, said, "I didn't realize it for many years, but the label, ESP, was my art."

Something the greats had in common was a search for meaning trying to quiet the mind while staring into the abyss. Don Cherry studied Buddhism; Alice Coltrane ultimately eschewed jazz in favor of a yogic path; John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders continued their journey to the One until I hope they finally arrived. Perhaps I can take a tiny bit from the masters who achieved great art and yet continued their search unflinchingly, without fear. With much contemplation and reflection fearlessly staring into that dark abyss-and knowing that Wax Poetics will continue to soar without me, I've decided to embark on a second chapter of my continuing journey...whatever may come.

And I finally scored a sealed copy of Journey to the One. It only took twenty-three years.

"You cover the music that's really inspired me as a musician and artist. So many legends that bubbled just underneath the surface but culturally impacted so many people."

"Wax Poetics distinguishes the music listeners from the music lovers"

"Wax Poetics is necessary reading for the intentional listener."

"People that know Wax Poetics have this strong sense of collecting and what music's really about"

What you'll find in all our journals...

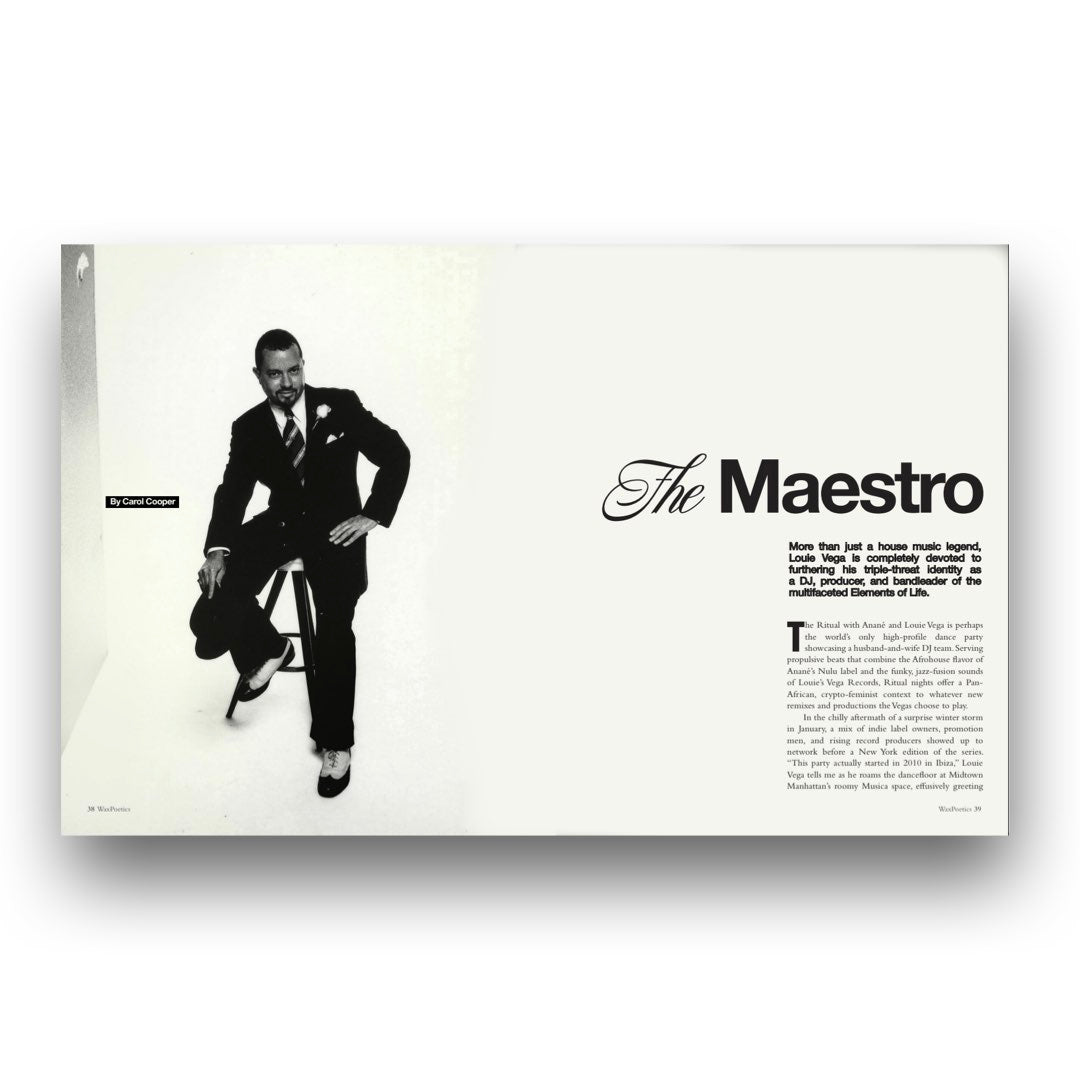

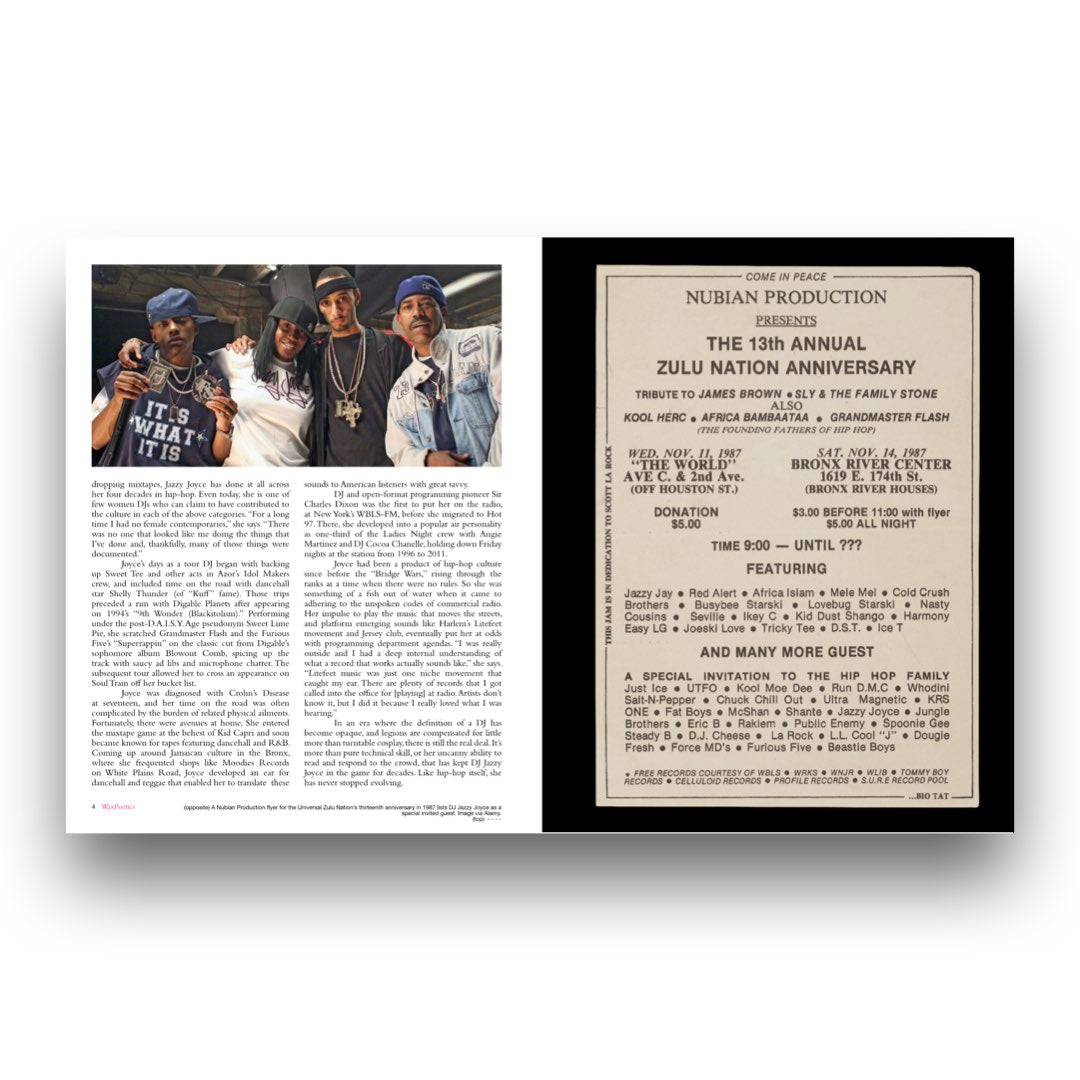

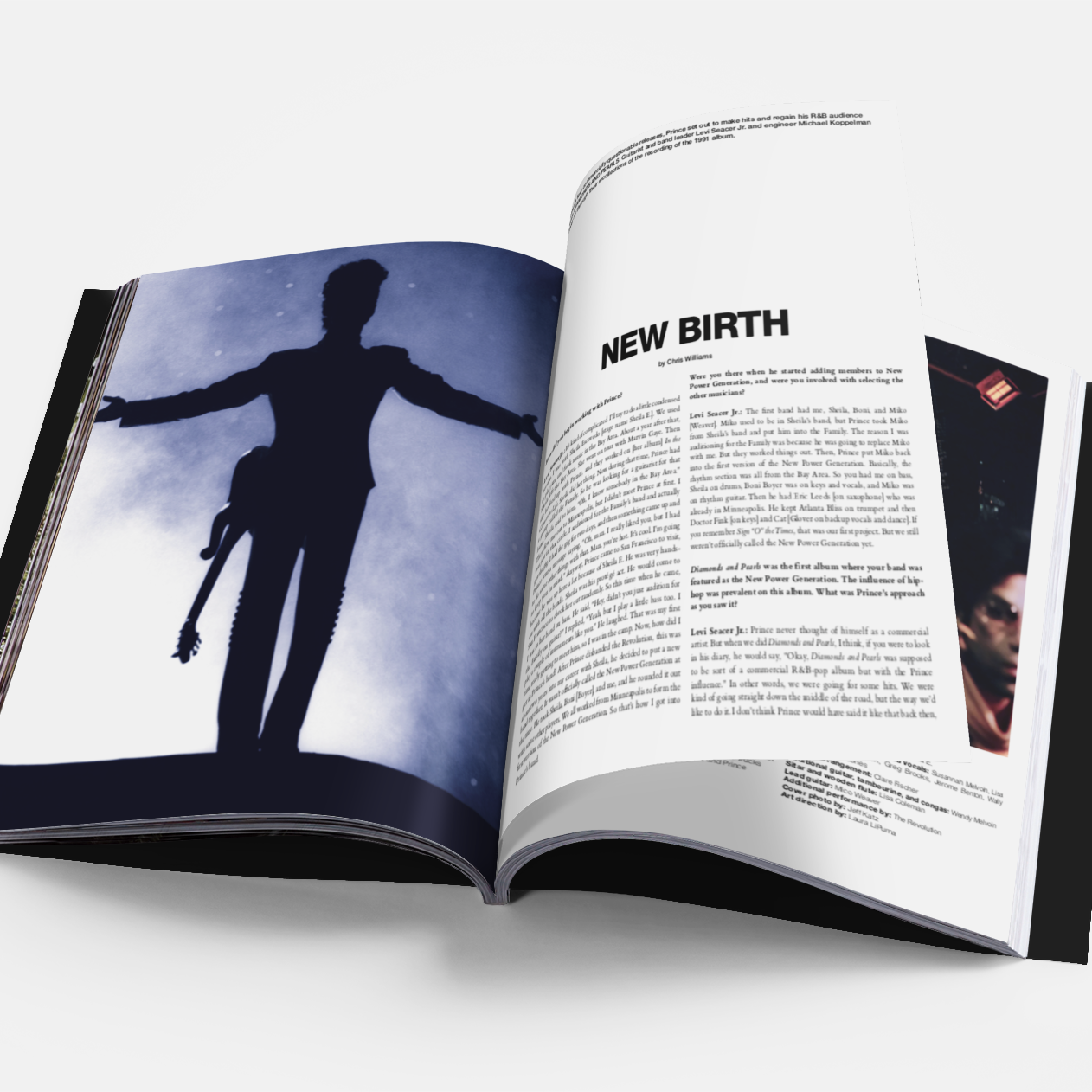

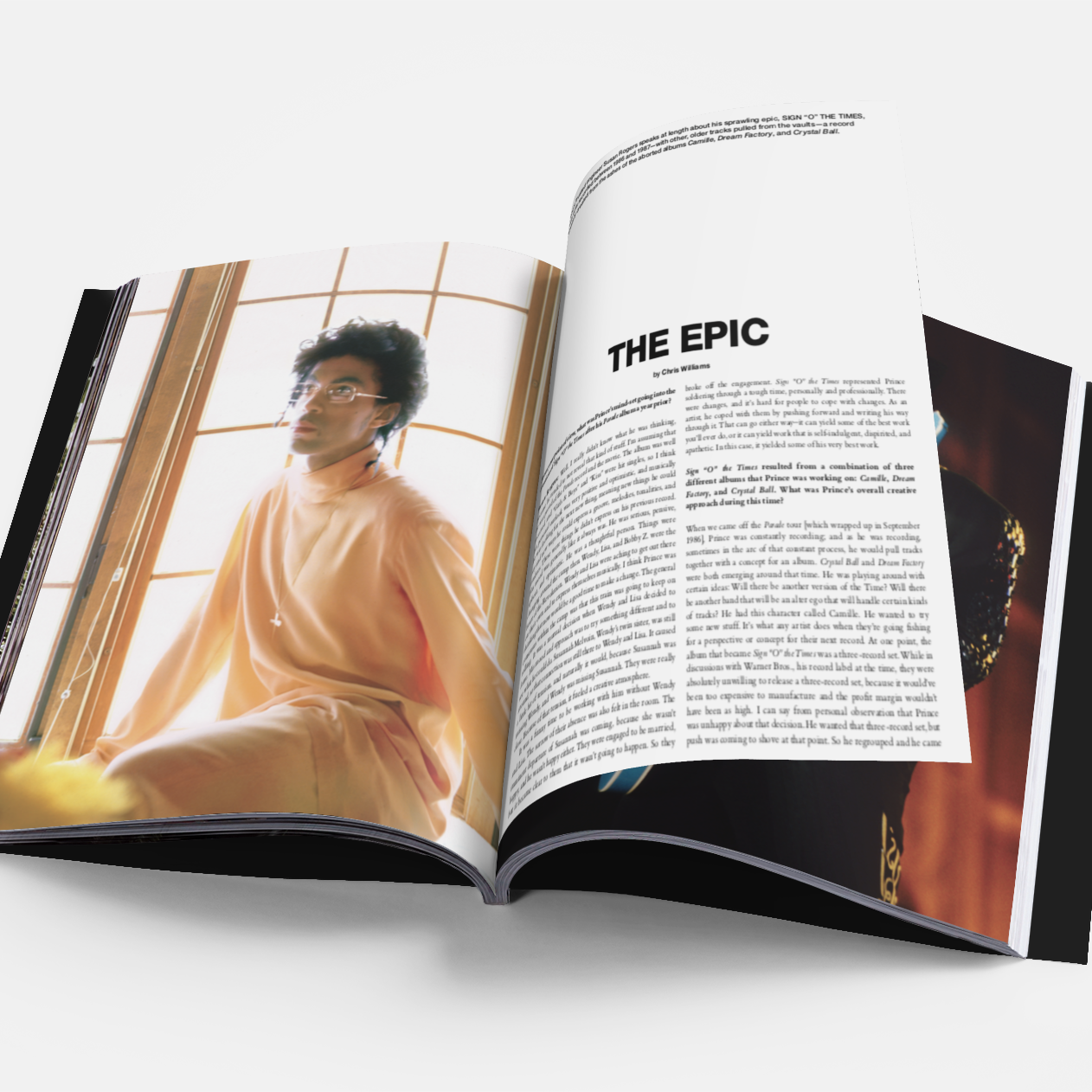

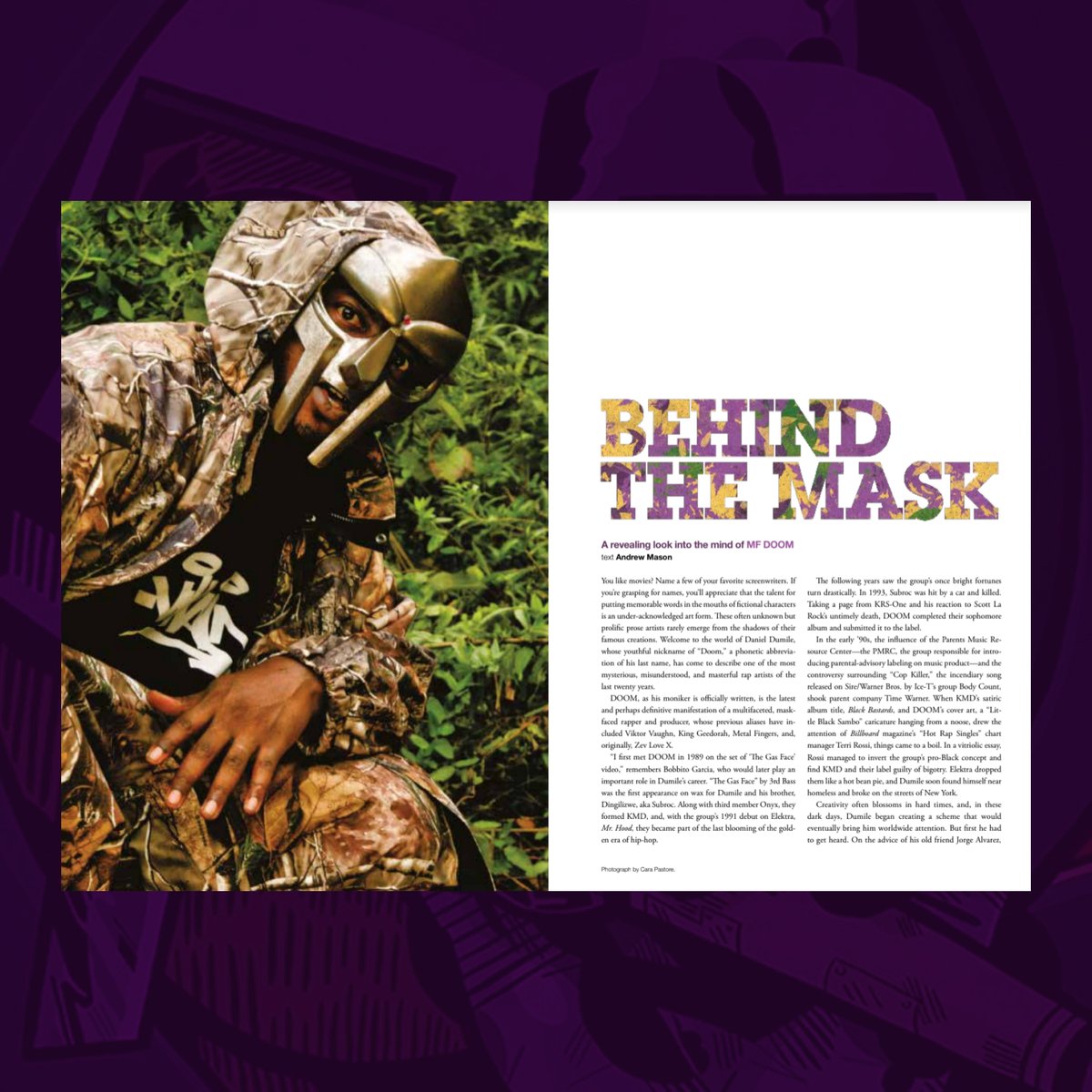

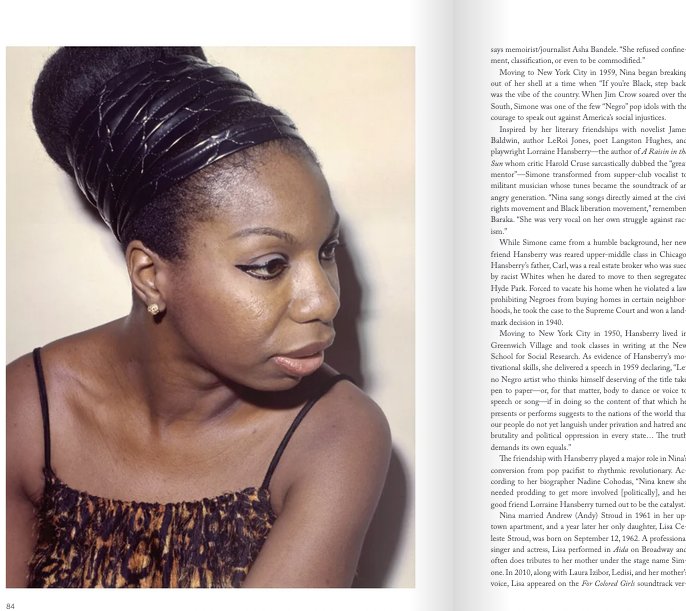

Classic & original photography

DEEP MUSIC STORIES

"i never knew that" knowledge