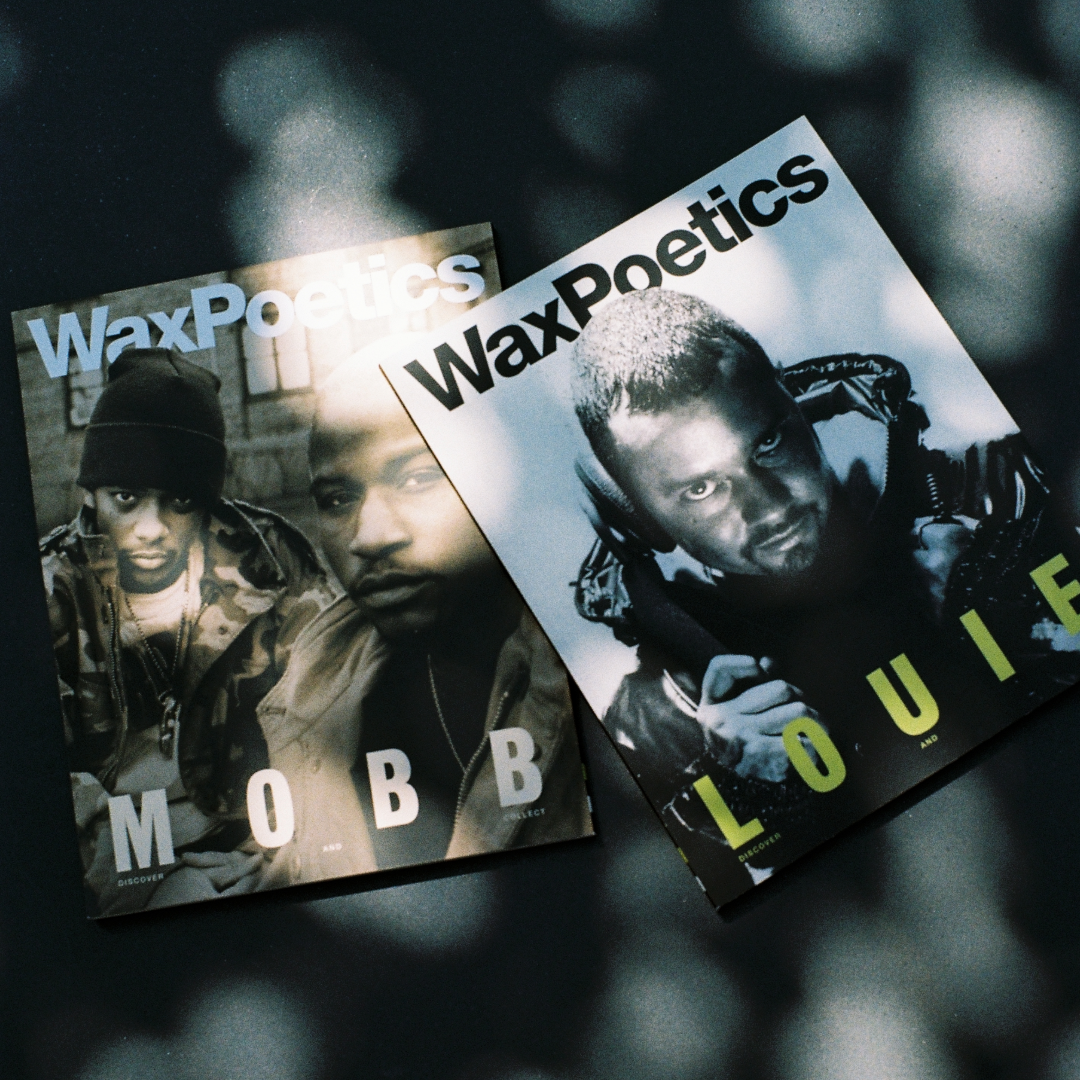

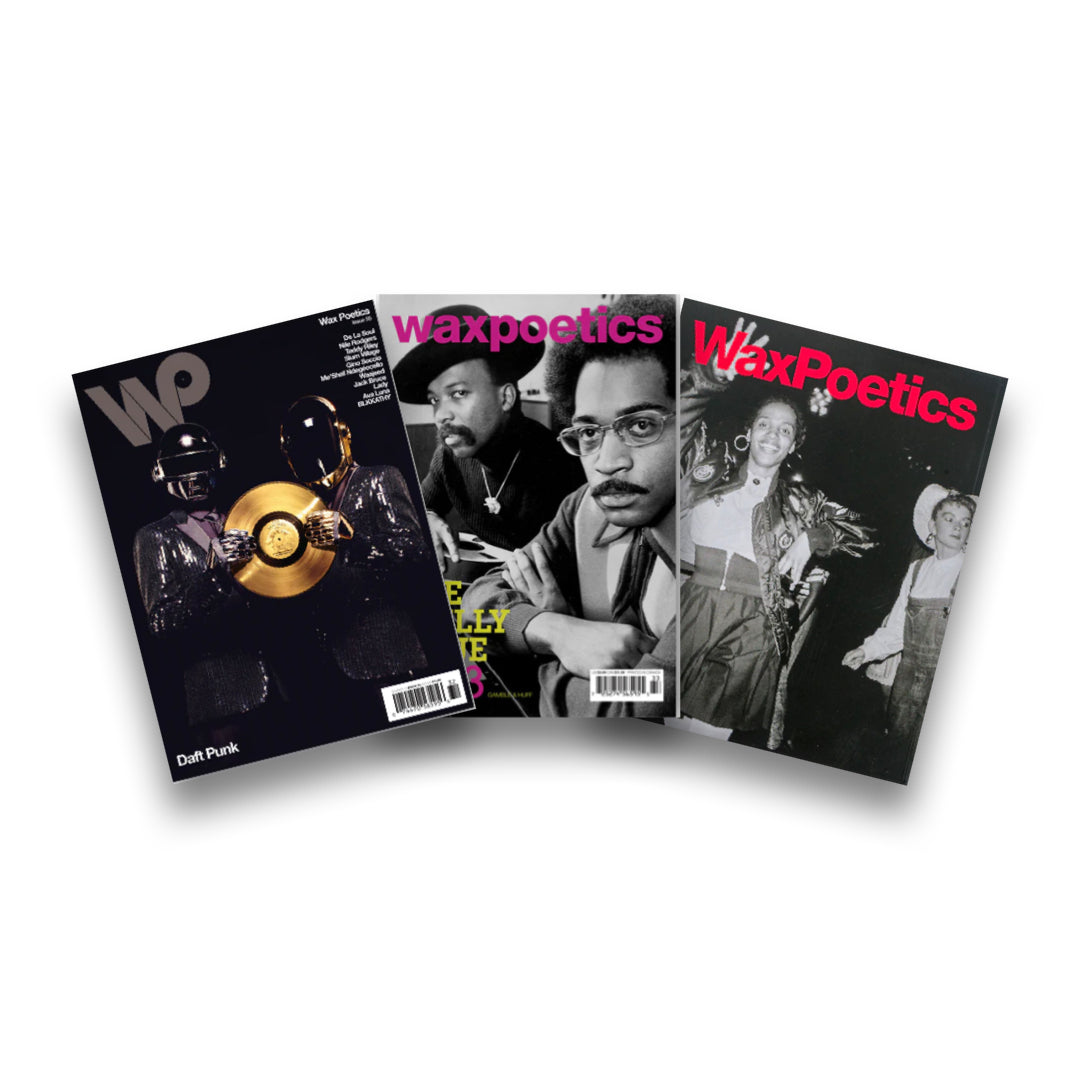

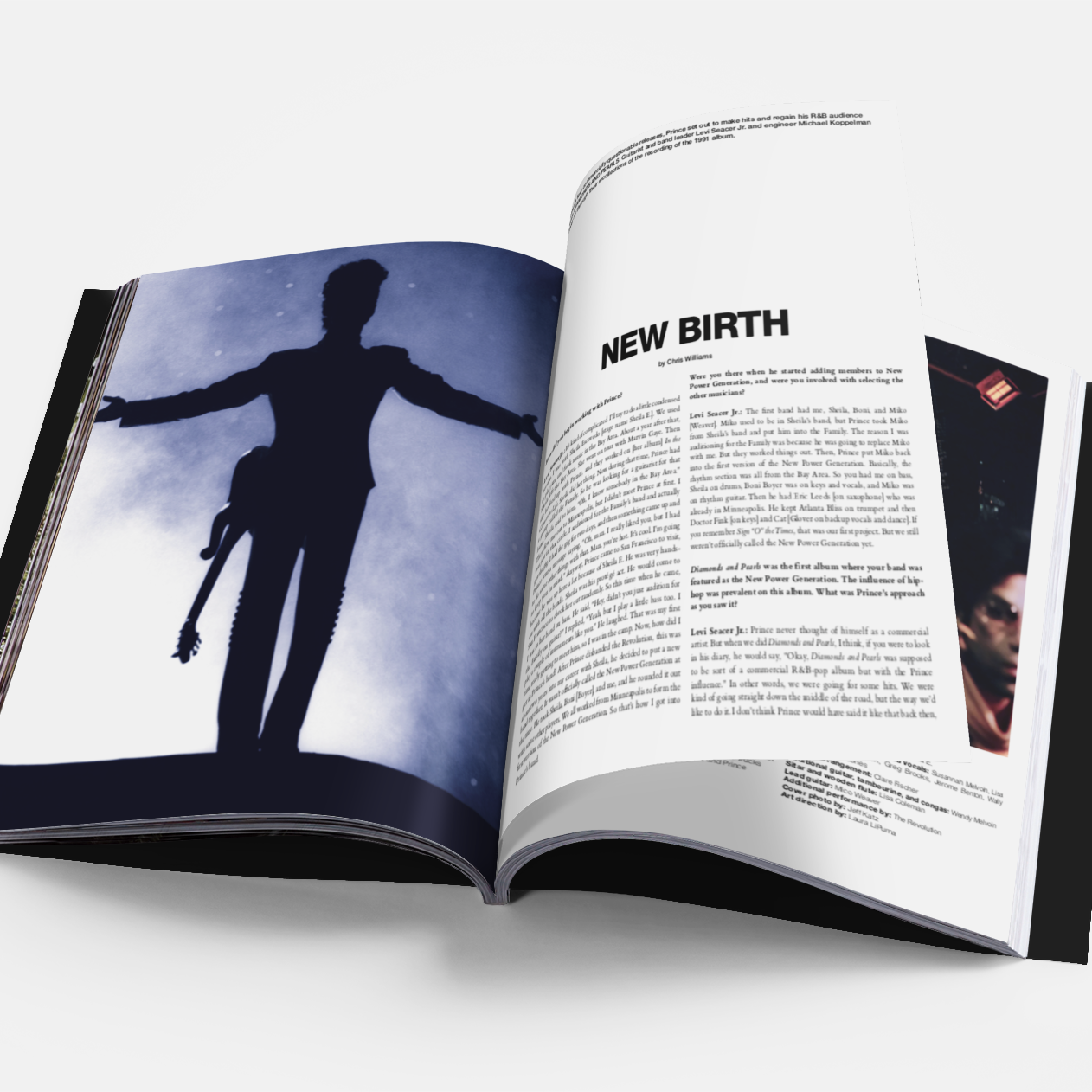

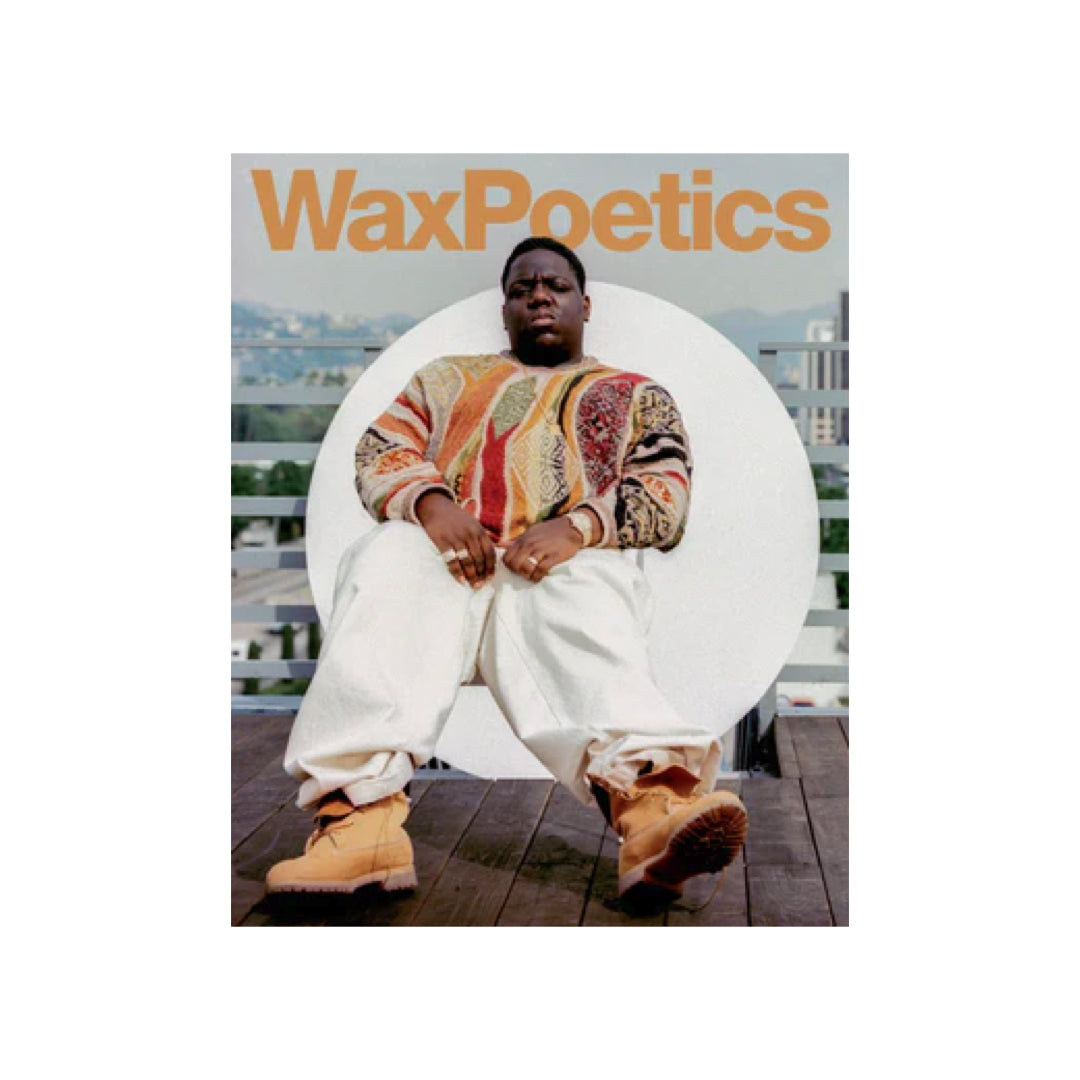

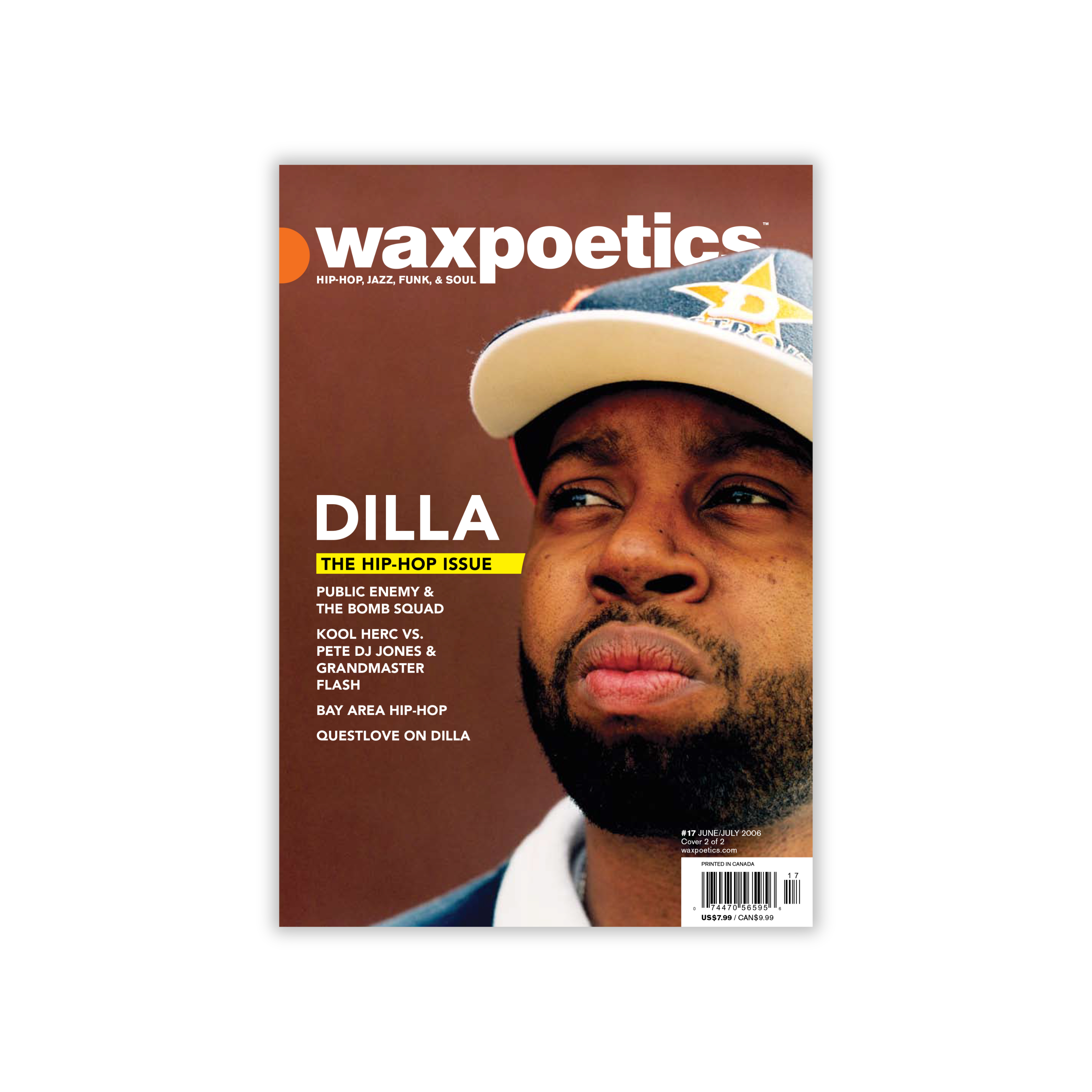

Thank you for supporting Wax Poetics and giving us a new birth, a new era, so we can continue to do what we've done best for the past twenty years: tell amazing stories. In gratitude, we deliver this Special Collector's Dance Floor Edition before our official relaunch in 2021, where we get off on the good foot with a newly designed website with weekly features and a couple heavy-hitting print issues.

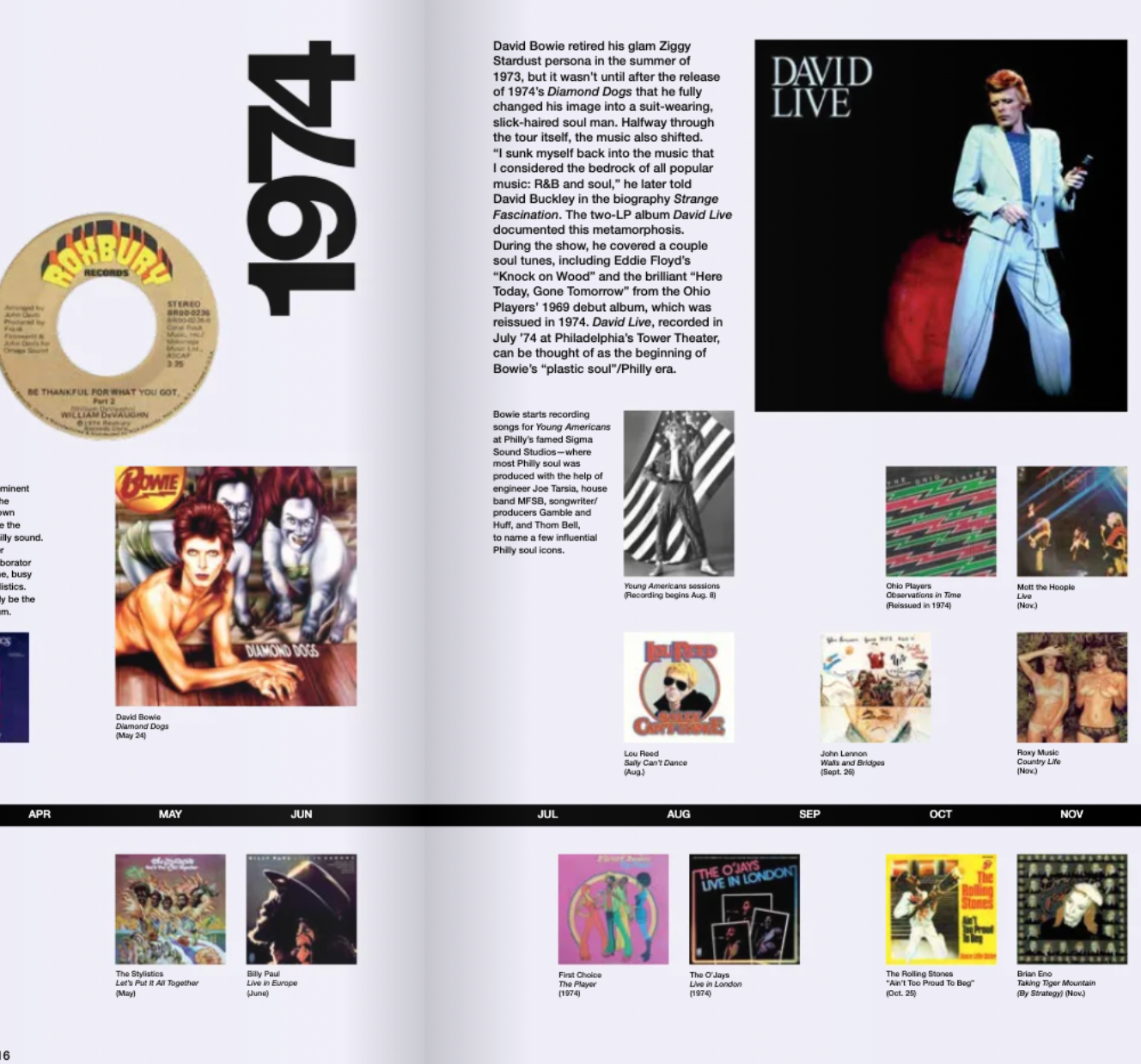

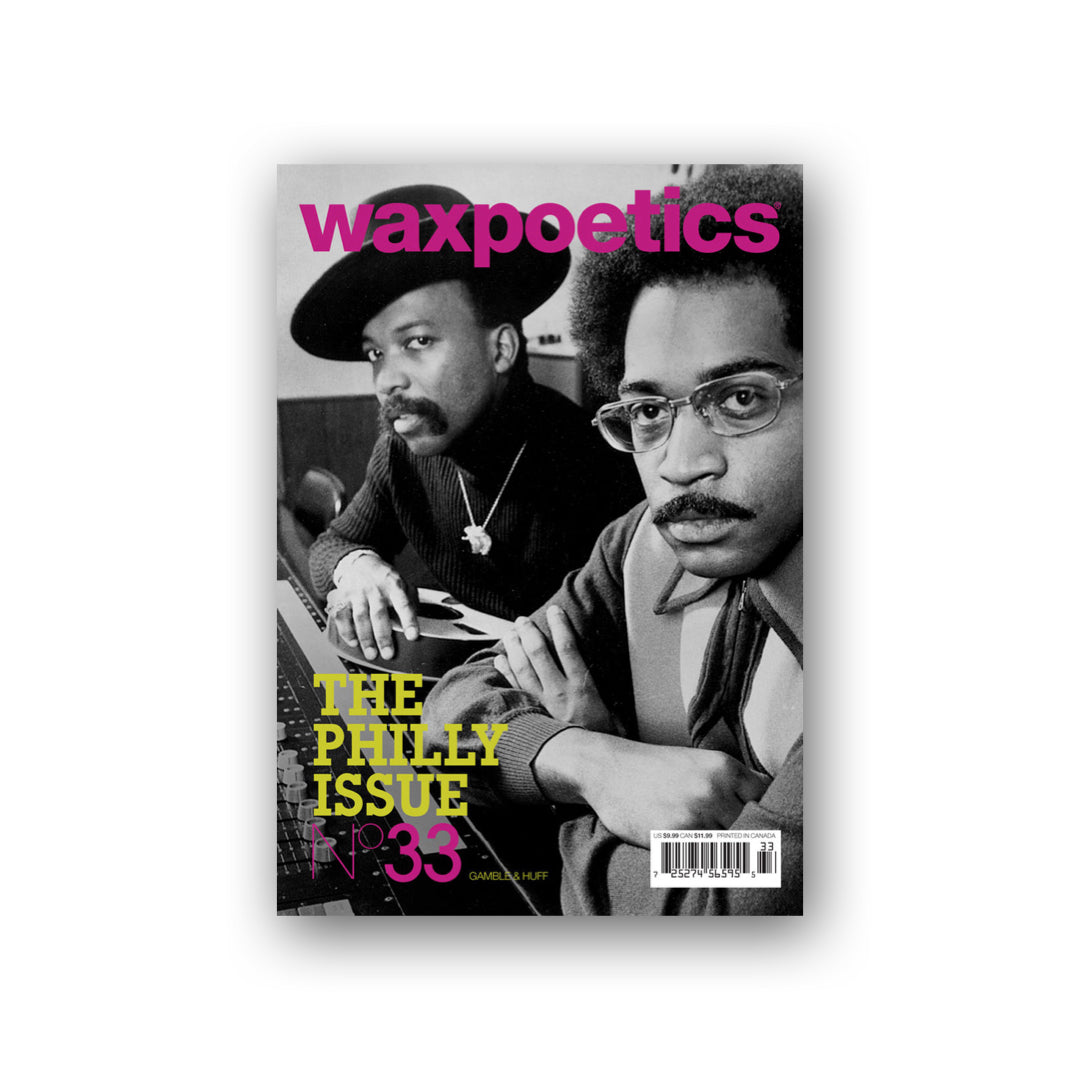

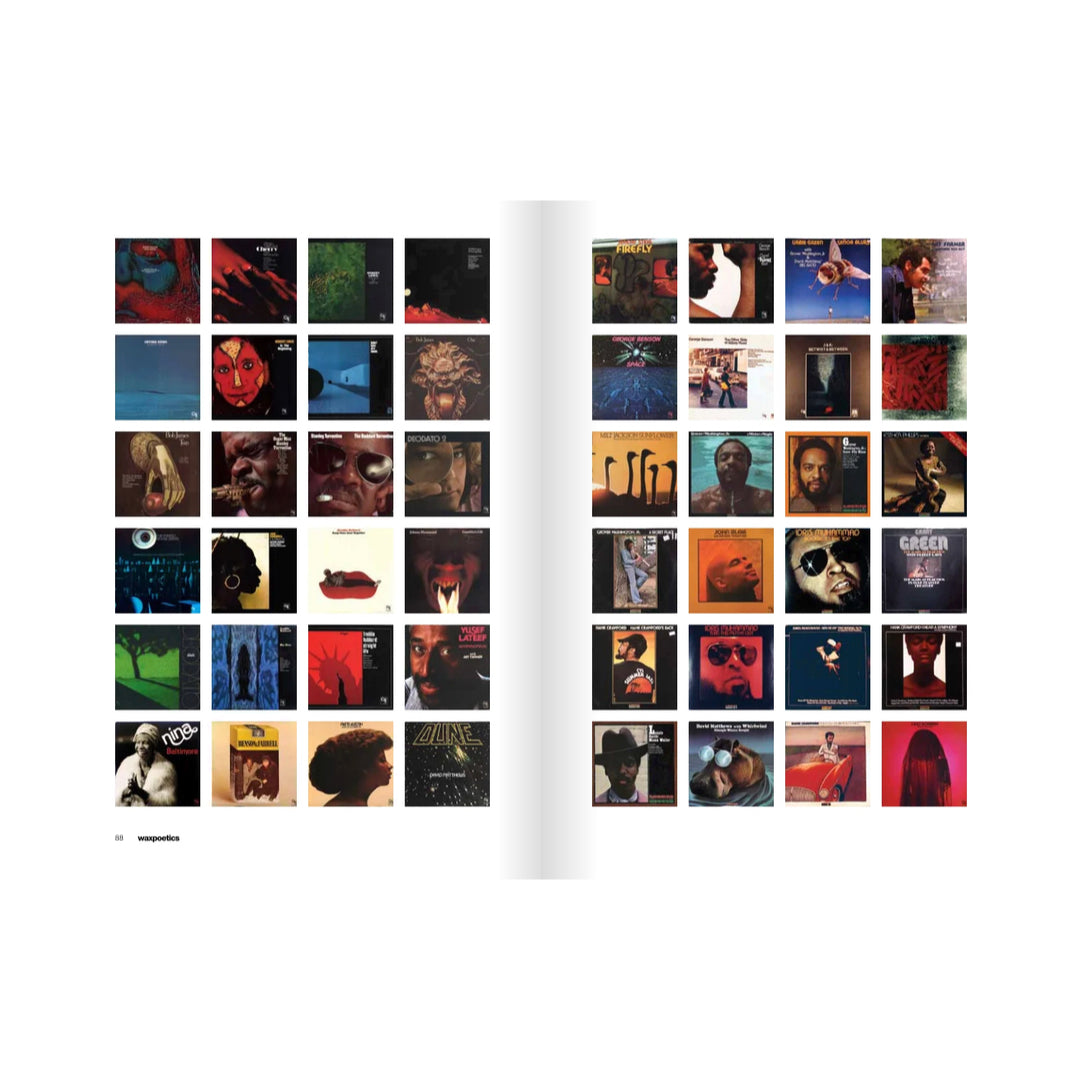

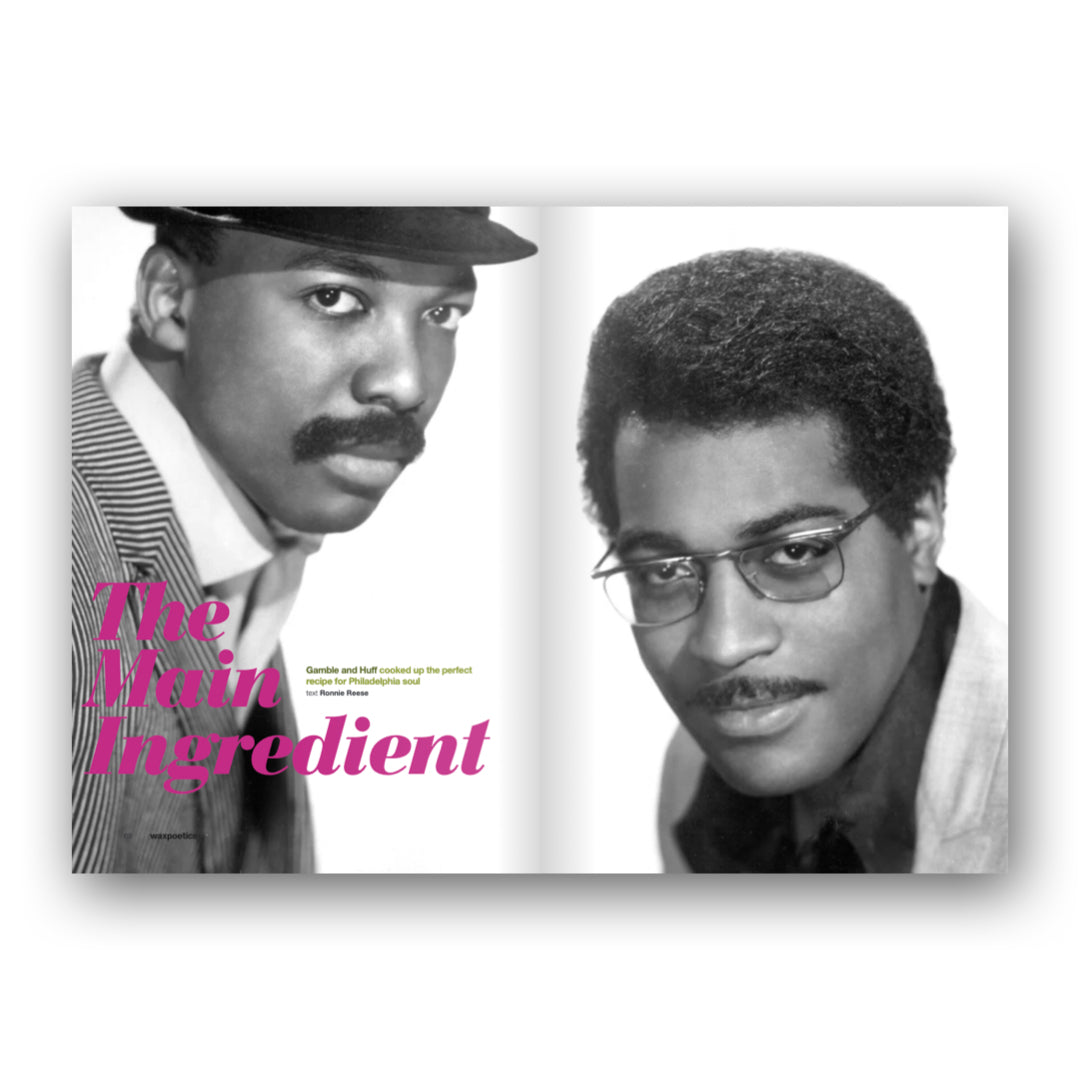

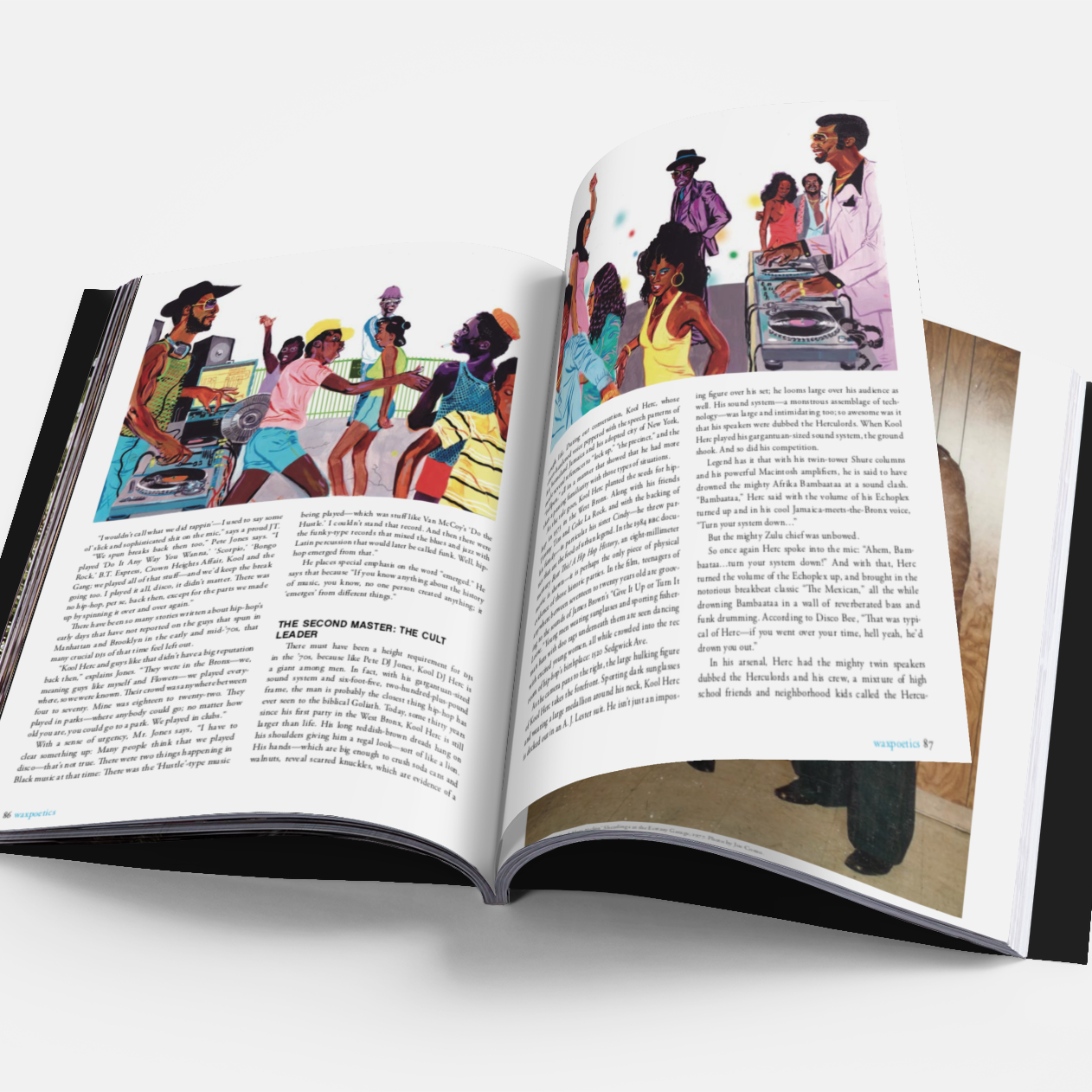

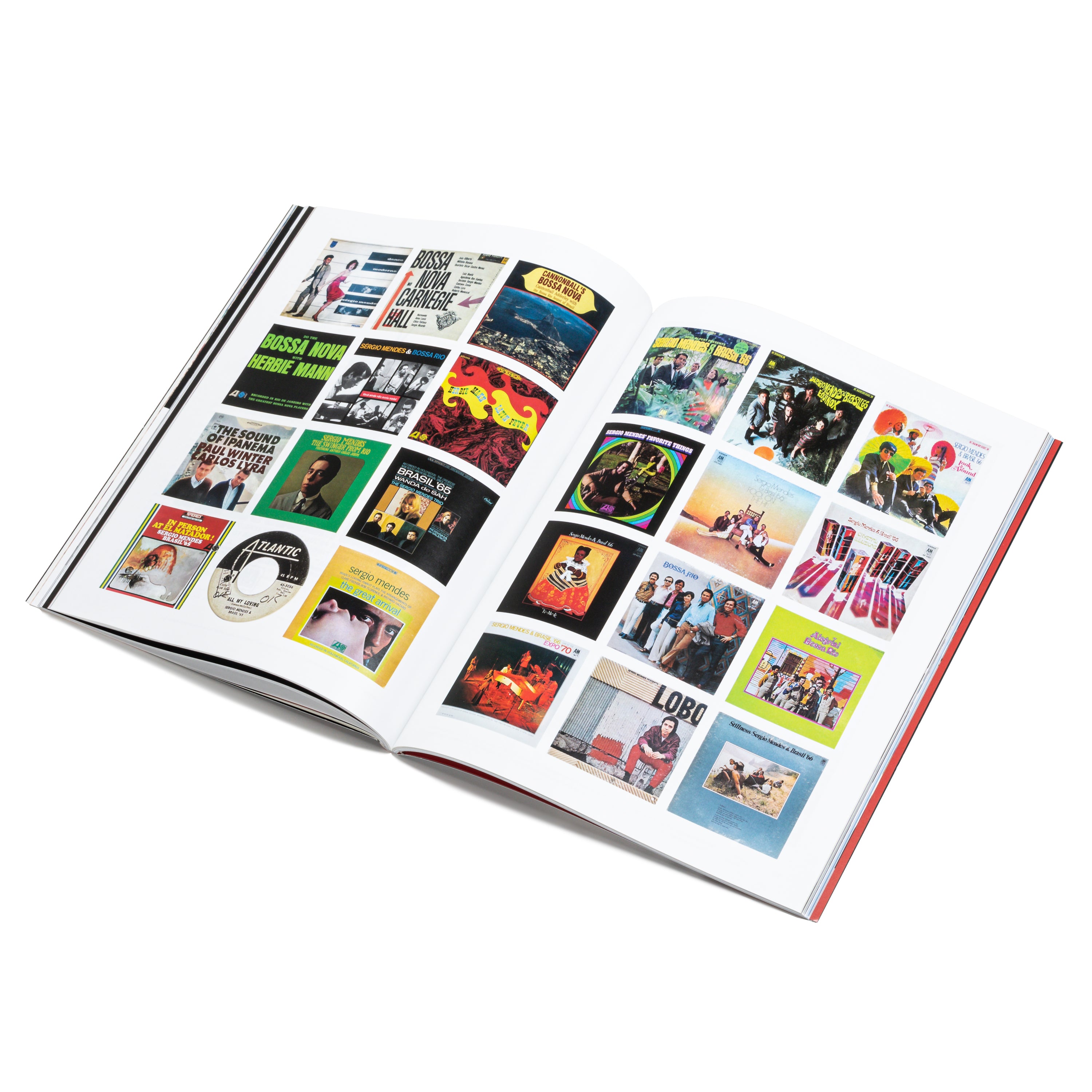

At Wax Poetics, we've always explored vinyl culture, and that significantly includes dance DJs, artists, producers, and their records; and the various histories and stories of the dance scenes throughout the decades- from Detroit techno to Chicago house. "Dance music" gets a bad rap in some circles, but the first record that iconic NYC DJ Danny Krivit mentions in his "12x12" article is James Brown's Get On the Good Foot. And Krivit was known to spin the funk band War and even the futuristic and epic synth sounds of Mandré-even if it cleared the dance floor. In the early '70s, long before disco had a name, much less a scene, the NYC gay community headed out to Fire Island, as future remixer Tom Moulton recalled, and danced to Al Green, Wilson Pickett, and Sam & Dave! Not long after that, songwriter/producer duo Gamble and Huff went from producing more traditional R&B to creating a new sound of Philly soul-replete with an orchestra and more up-tempo rhythms- that served as a catalyst for the soon-to- be ubiquitous disco sound.

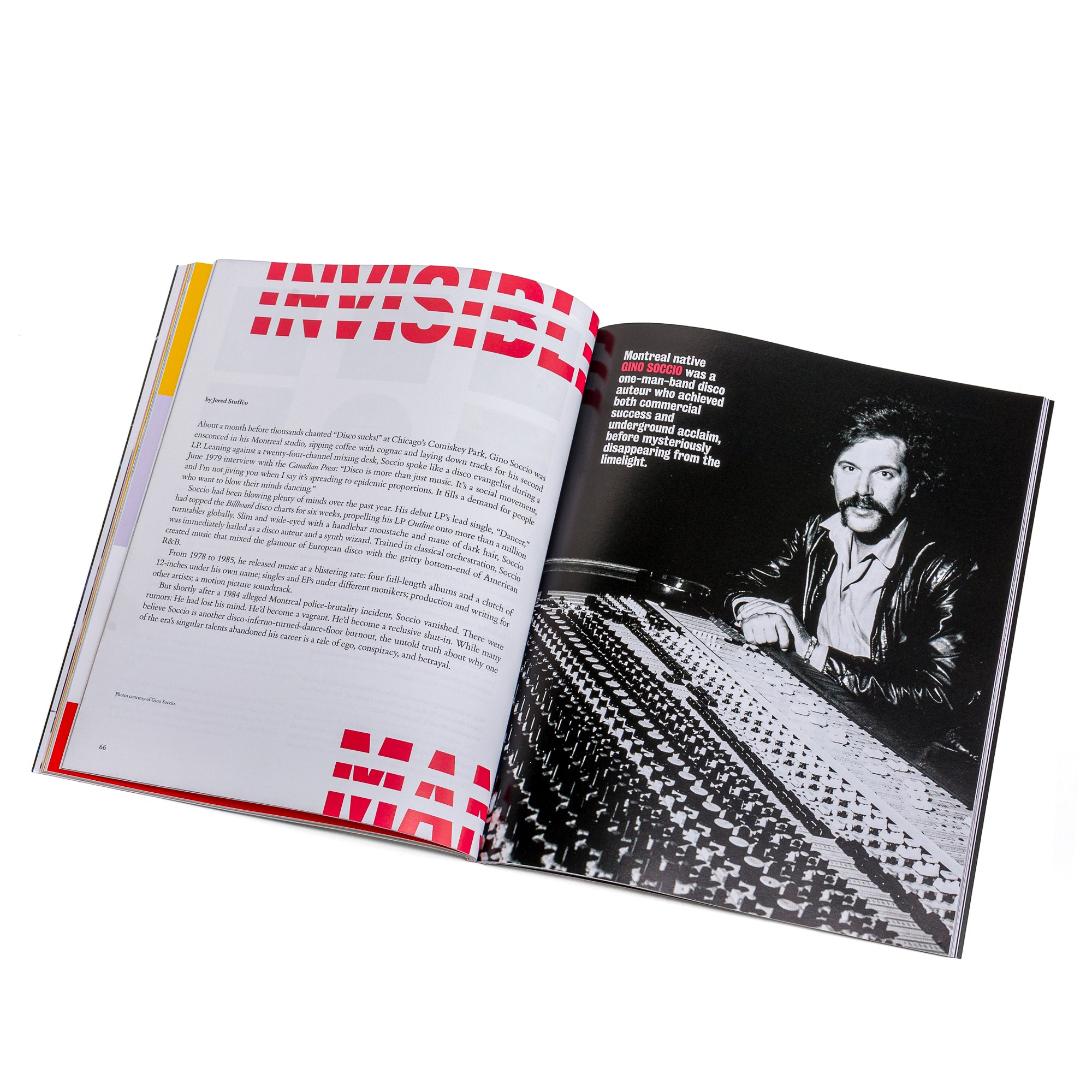

To be honest, some of my favorite WP articles of all time are about dance music-like our most-read-ever piece on producer Gino Soccio, a tale of "ego, conspiracy, and betrayal," writes the author. Another favorite is about New York's Continental Baths, a gay bathhouse (and club) that in 1968 (pre-Stonewall Riots) thrived in the face of oppression- homosexuality was still illegal in the city and much of the country. We strive to

tell these stories of civil rights and equal rights; and to be frank, it's difficult and downright dishonest to try to separate issues of social justice from music. Like the Baths story (which will be available on our site), dance music stories often tell the pivotal social conditions surrounding these scenes, and that is why these classic stories are consistently relevant and poignant. But they also tell the tales of the people involved-and the Baths would birth the careers of two of the most celebrated dance DJs of all time, Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles.

For a minute this summer, during the Black Lives Matter protests across the United States, it felt like a change was gonna come. But while the moral universe may bend toward justice, the arc is, unfortunately, long, and this nation is divided as ever, with one side not even wanting to hear the word "racism." But we never shy away from shining a bright light on social issues, and for this edition, our two new stories take a look at racism and segregation, but in 1980s England-times of class warfare and forced austerity of Thatcherism, with a common denominator of innovative music.

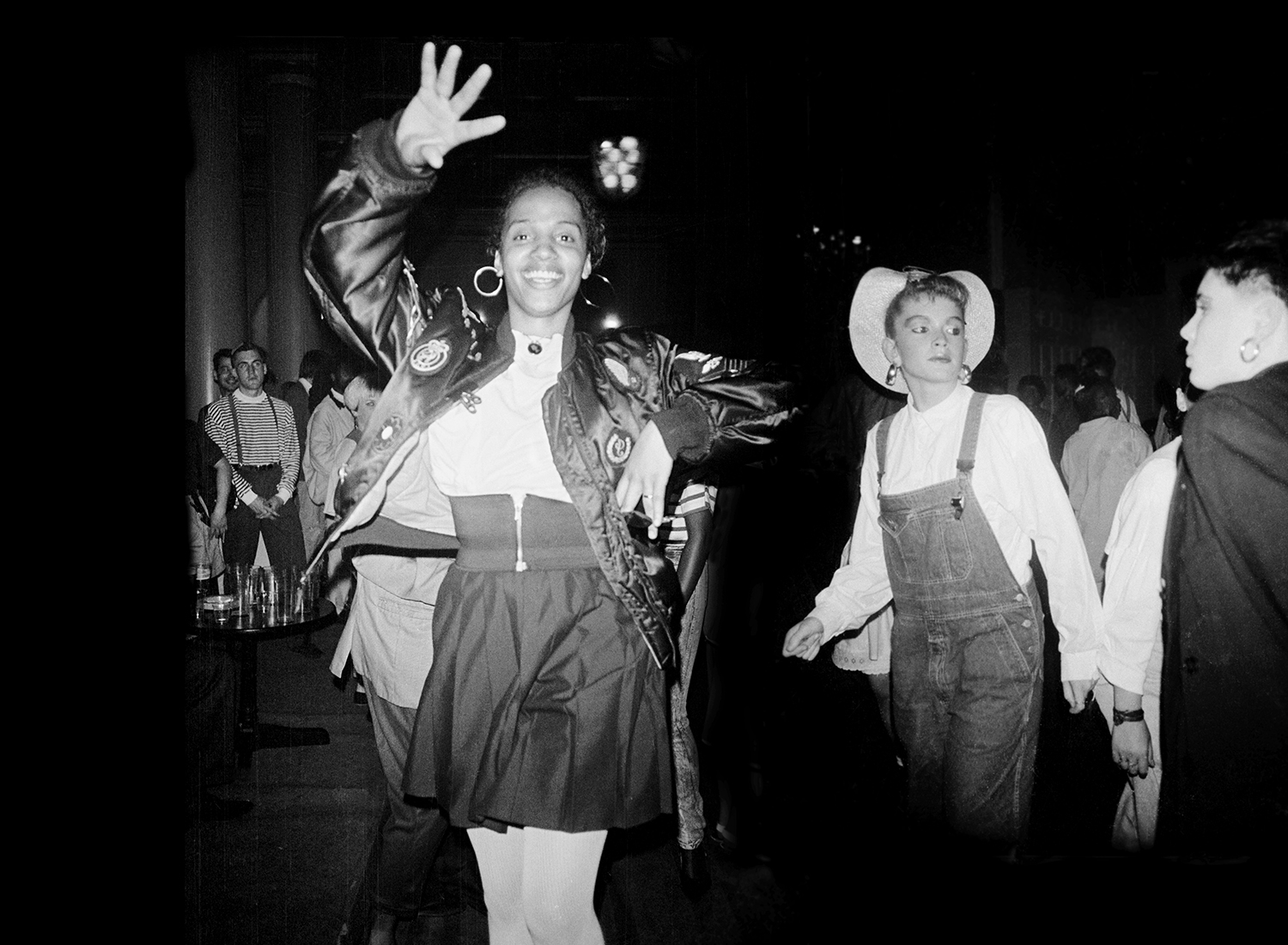

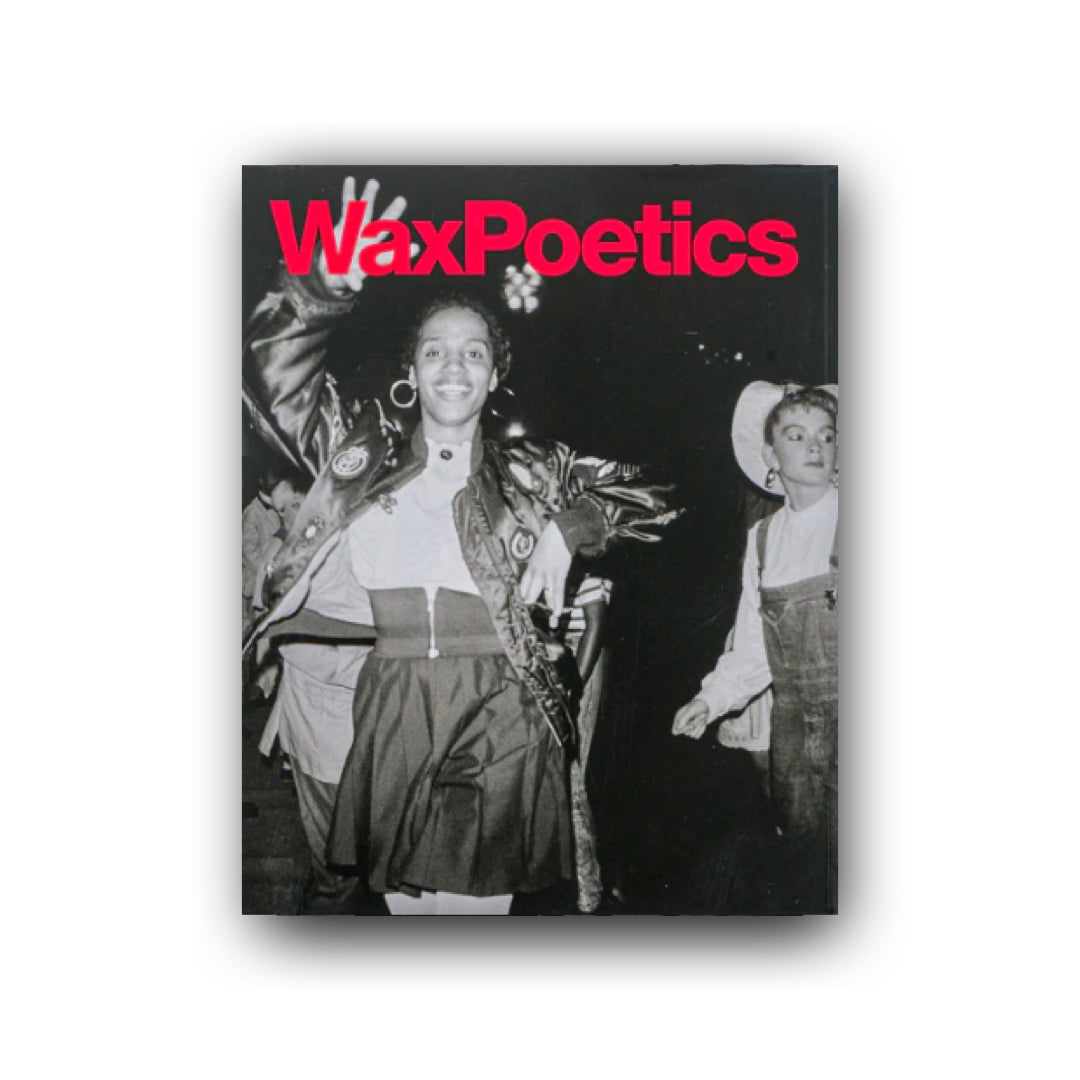

First we start in the North England post-industrial town of Sheffield, where two friends, Winston Hazel and Richard Barratt, helped bridge the gap between the jazz-fusion All-Dayer dance scene and the future funk of "bleep techno." With closing factories and high unem- ployment in the early '80s, Sheffield mir- rored her sister city Detroit. Groups of young DJs and musicians in both cities embraced the do-it-yourself bootstrap entrepreneurial spirit that was part of both Thatcherism and Reaganomics propaganda, and created two import- ant scenes that would end up bouncing ideas back and forth across the Atlan- tic. Electro records (like Detroit's Cy- botron) made it to Sheffield and changed its musical landscape. When Hazel first started DJing around town, his Black friends couldn't even get into the clubs

in a mostly segregated Sheffield. But with the founding of their Jive Turkey dance night, a multiracial crowd con- vened to celebrate their love of this bur- geoning electro-funk sound, and soon Sheffield would become ground zero for new homegrown electronic music of its own, helping to birth the U.K.'s house revolution.

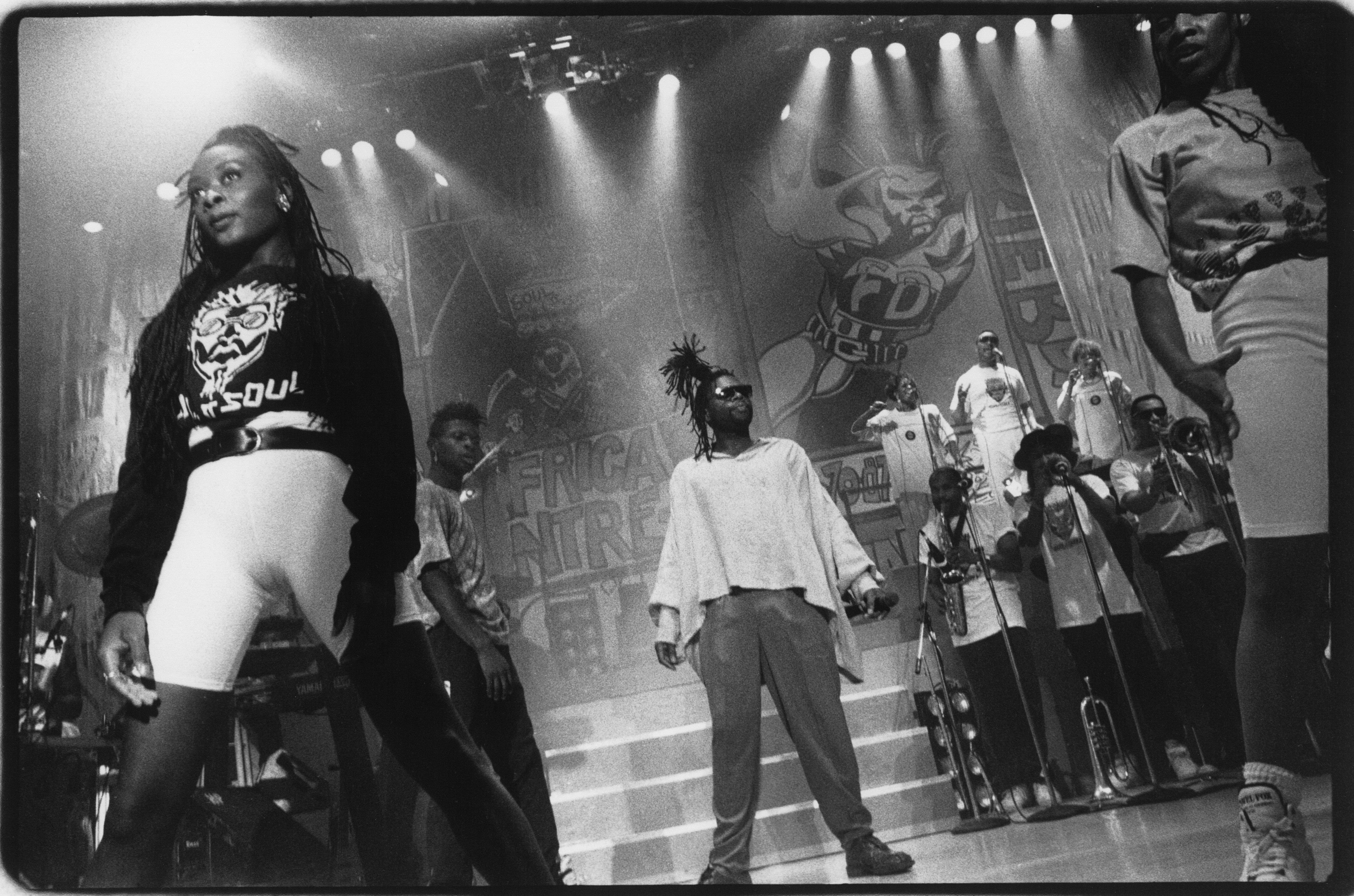

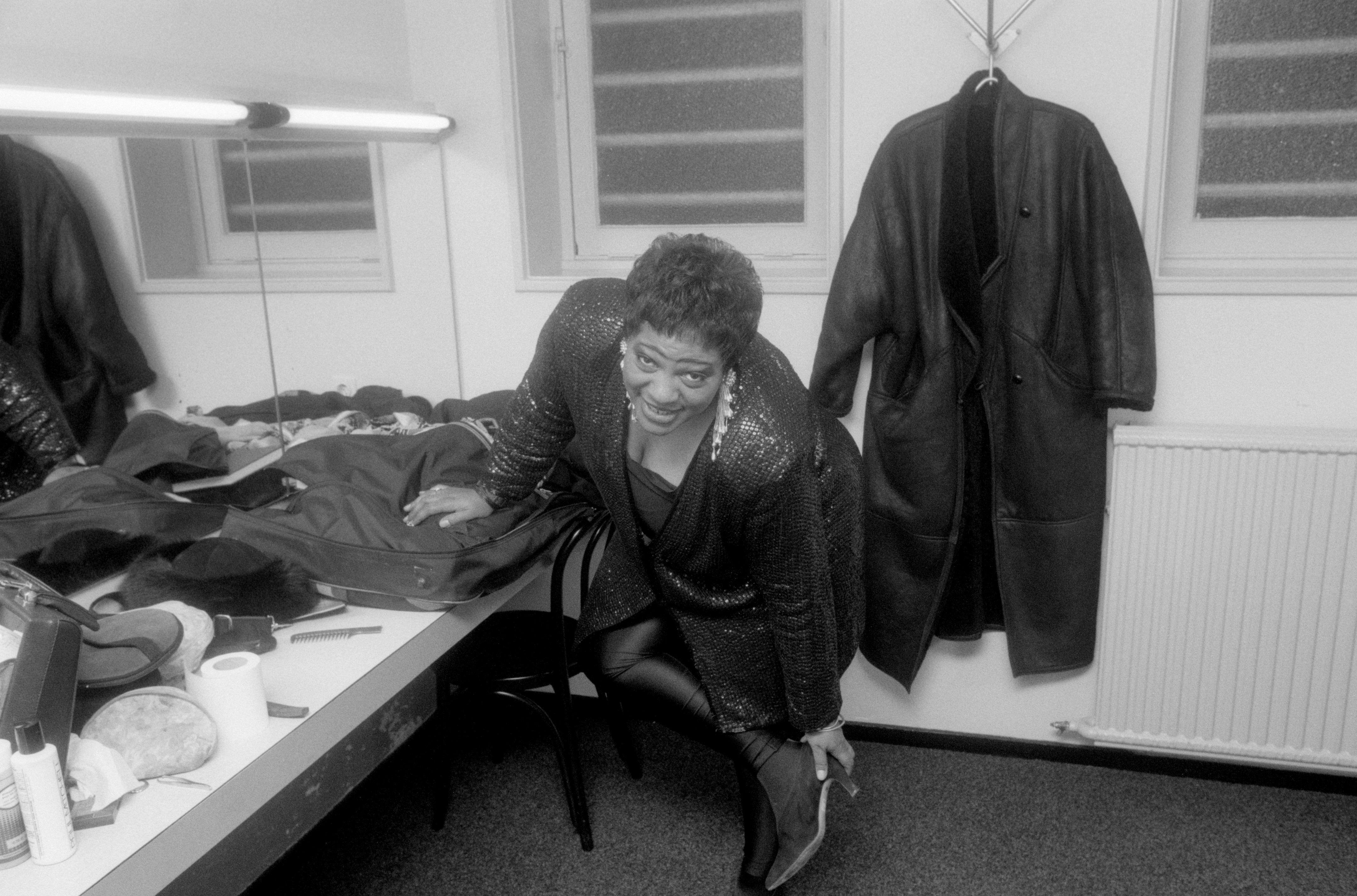

Meanwhile in Camden, London, a Thatcherism-era entrepreneur named Jazzie B took his innovative and all- inclusive concept of a sound system to great heights-first as a groundbreaking weekly dance party and then as a musical collective that generated two worldwide hits, "Keep On Movin'" and "Back to Life (However Do You Want Me)," both propelled by the unrivaled Caron Wheeler. But even such global acceptance couldn't solve the glaring racial issues at home. While the group's 1989 debut album garnered two Grammys, the Black English homegrown dance/soul album was snubbed by the U.K.'s own Brit Awards, a move that smacked of institutionalized racism, especially as the Best New Artist award went to a White artist whose song copied the same drum pattern as "Keep On Movin'." The whole thing reminds me of a lively quote from Miles Davis's autobiography: "I got into some controversy with the Grammy Awards people in 1971 by saying that most of the awards went to white people copying black people's shit, sorry-assed imitations rather than the real music."

Well, it's not 1971 anymore, and it's not 1989 either-and it's been nearly twenty years since WP was created to fight institutional racism by putting Black music on a pedestal-but as 2020 has shown us, it's not time to sit silently and idly by when our brothers and sisters need us most. So keep fighting the good fight, and we'll keep shining the light.

Keep On Movin'