Originally published in Wax Poetics Vol.2 Issue 2 as part of the Wax Poetics x Patta series.

Even though Gerard “GE-OLOGY” Young’s contributions to the pantheon of music and visual art have been wildly prolific, his life story has rarely been told. But condensing his lifelong pursuit of ultimate creativity to a manageable size is a tricky business. A week after he and I recorded a pair of consecutive six-hour interviews, I decided to shoot over a considerably shorter query, in text form: Can you summarize your artistic path to this day, in one word?

“Yes,” he responded. “Inspired.”

I’ve known Gerard personally now for twenty years. We formally met on the set of a music video I was directing for the Jigmastas and Sadat X’s song “Don’t Get It Twisted” in late August of 2001, New York City, the World Trade Center towering high above as I set up the video’s final party sequence atop the roof of a Lower East Side tenement. A few years later in 2005, I’d release his own debut—and to this date—lone full-length album, GE-OLOGY Plays GE-OLOGY, on my now defunct imprint Female Fun Records. The colossal thirty-song project was an opus-sized trek into Geo’s evolved production prowess: technical hip-hop tracks, a vibrant soulfulness framed by deep, filtered bass lines, an innate feel for drum programming, and the brilliant ability to evoke complex feelings through easy head nods. It was a truly inspired work that seemingly came out of nowhere. Chasing inspiration can lead to creation, but often the deeper story is what’s behind the curtain. For GE-OLOGY, soul, gospel, disco, funk, hip-hop, and old-school futurism are all essential building blocks, and how he came to deeply resonate with them is where the story begins.

In East Baltimore, December 1970, Gerard Young is born, the first of two boys, to Gerard Sr. and Debi Young, just seventeen when they brought their son into the world. Geo’s earliest years were spent on Woodbourne Avenue, Northeast Baltimore, in a working-class household warmed by the feeling of a full family of multiple generations, various sets of record collections, and Grandma’s classic wood-trimmed Kimball organ. In 1975, right around the time the first 12-inch singles were being released, young Gerard began visiting record stores regularly. After classes at Elmer A. Henderson Elementary, his grandmother, a teacher, would routinely take the young G to some of Baltimore’s many record stores. As frequent favorites like Kozy Korner Record Shop and Music Liberated became part of a regular after-school tradition, Gerard often kept her waiting for hours as he flipped through 45s.

Doodles of trucks on bedroom walls would eventually turn towards long studies of his father’s record collection. The dynamics of 1970s long players started to make their impression. Crucial releases like Earth, Wind & Fire’s Last Days and Time, Herbie Hancock’s Sextant, and Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew deeply affected him, serious sounds from Black titans that pushed back against the status quo of a post–Richard Nixon America. A deeper impression came from their covers, gatefolds whose visuals practically released hypnotic gases as Geo poured over them. The works of visionary painter Abdul Mati Klarwein accompanied a backdrop of subversive, psychedelic horns, percussion, and arpeggios. The power-filled voices of Maurice White and Gylan Kain matched images of an African American community returning to long-unforgiving B’more blocks after fighting someone else’s war. Back in the house, it was: “Don’t touch your father’s records,” Geo remembers with a laugh. Forbidden archives—until his father wasn’t around. Pops pushed a mean white Oldsmobile Ninety-Eight, and when it pulled off the block, young Geo seized his chance to flip through the crates.

For Gerard as a child, an undeniable turning point was being taken by his parents to Baltimore’s storied Odell’s nightclub for a special Easter Sunday “kiddie disco” matinee. Dressed to impress in their Sunday best, a young Gerard saw and heard firsthand the makings of what a great discotheque is supposed to be. Baltimore’s club history is just as rich and varied as its many record shops, and one of its most historic was undoubtedly Odell’s. Considered by many the Paradise Garage of Charm City, the famed venue was opened by the late Odell Brock in 1976 as a family-run endeavor. Their motto back then was You’ll Know if You Belong, and for a kid like G, right then and there he knew exactly where he’d fit in. Within a few years of opening, the club upgraded its sound with a system built by none other than famed audio engineer Richard Long. Odell’s was already destined for the history books, and this new sound system solidified that status (upon its eventual closure many years later, the same equipment was moved to DJ Wayne Davis’s club Paradox, another Baltimore institution). Richard Long is one of the most-lauded sound designers in nightclub history, having created rigs for Studio 54, Zanzibar, Area, and Bonds International, and his sonic aesthetics pumped through Odell’s. There’s a common Easter saying that to plant a garden is to believe in tomorrow, and as little kids danced away in tweed seersuckers, Gerard began to realize how important this environment could feel. “I never experienced anything like that before,” he says. “It changed my life. First time seeing a big mirror disco ball, the huge speakers, and being in a space like that was incredible. That definitely had an impact on me. What also had an impact without me even realizing it was that since my parents were young, they were still going to parties. There’re photos of my parents while my mother’s pregnant with me, taken at venues pre-dating Odell’s, so I must have been feeling the music vibration in the womb.”

When G wasn’t on the quest to construct the perfect paper plane or become the quickest to solve a Rubik’s Cube, he modeled himself after star Dallas Cowboys running back Tony Dorsett, mowing down the competition in hard-hitting tackle football anywhere from neighborhood lawns to the unforgiving concrete. It was a formative time as his boyhood hobbies were shaping to be his life’s work. “I was eleven years old when I first started to DJ,” he reflects, forty years later. His first audience, a room of one, was Fernando, a classmate in middle school at St. Mary’s. Transmitting via telephone a thirty-minute broadcast from stereo speaker to phone receiver, Gerard flipped his dad’s Realistic mixer with a mismatched pair of turntables. One, his kid brother’s Fisher-Price, the other, a model he won as a second-place prize at an annual candy sale. His mission to master cuts and blends would eventually dethrone his shiny brass one-time weapon of choice, a trumpet he picked up at the age of nine.

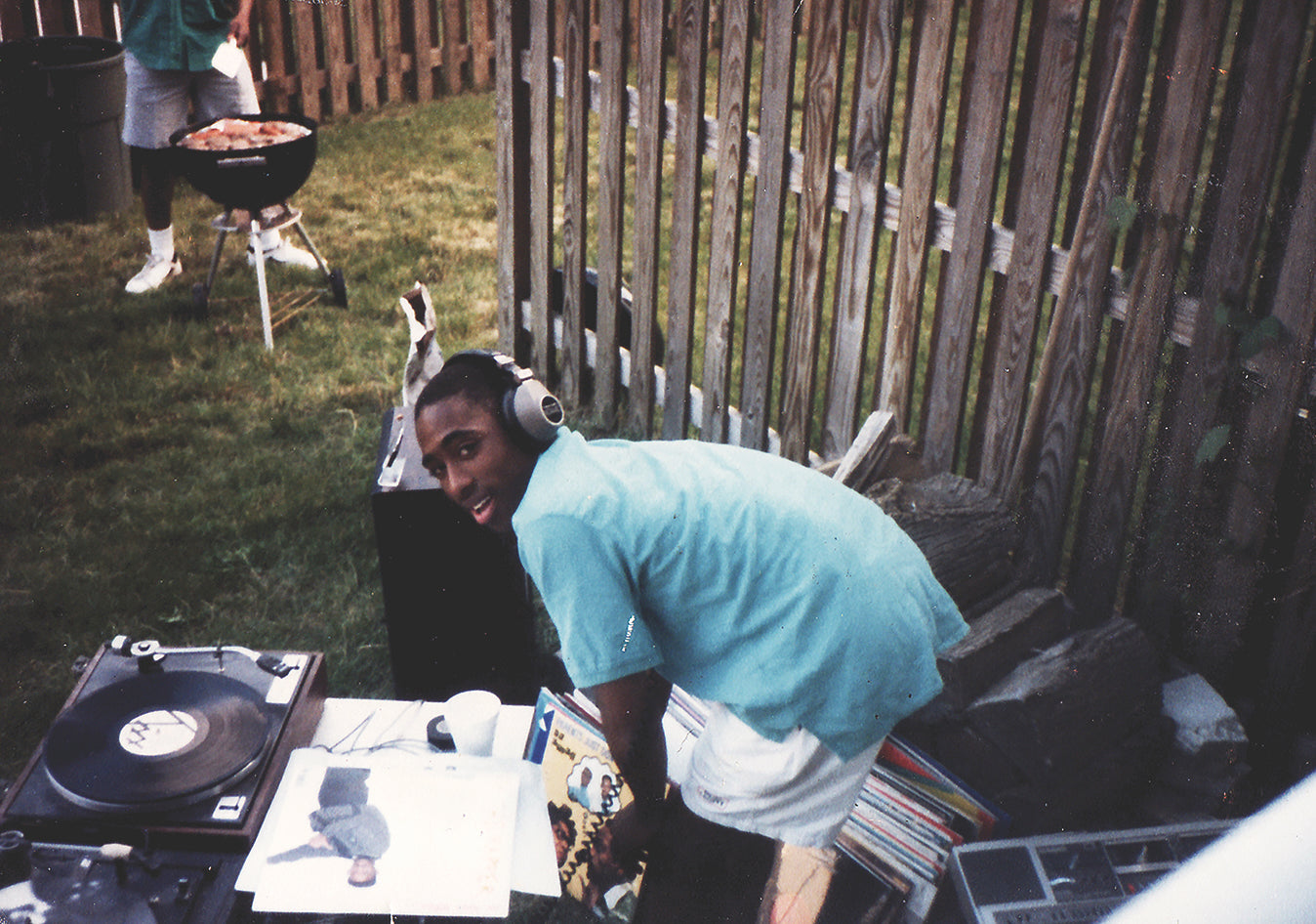

The Baltimore School of the Arts, located in the historic Mount Vernon section of Central Baltimore, is a magnet for actors, dancers, musicians, and visual artists alike, and it was here that Gerard entered high school. By this time, he had dubbed himself DJ Plain Terror and met the guys who would form Born Busy, as they christened their group. The crew consisted of friends Darrin Bastfield, Dana Smith, and Tupac Shakur, with Gerard, or rather DJ Plain Terror, as the musical backbone, two sets of friends who had formally faced each other in that iconic hip-hop setting—a lunchroom-hallway MC battle.

But first, let’s set the stage. As Gerard recounts, “Years earlier, there was a Mother’s Day fair happening at my little brother’s school. When I arrived, I could tell that he was really proud and happy that his big brother was there. He started introducing me to his friends. But later, I noticed these older kids, and this one particular kid rapping that had a T-shirt with iron-on letters that read ‘MC New York.’ I don’t know why he stood out, but something was different about him. It caught my attention watching them laughing and rapping, but then that was it. I didn’t even think about it after that.

“Maybe a year or so goes by, then I see him again at my school,” continues Gerard. “He had a very unique look, so I remembered him. I was like…‘Yo, that’s the same dude I saw before!’ I definitely wasn’t expecting to see him at my high school. Soon there were rumors about some new kid at school from New York that raps. But we were the b-boys at school, so we were like, ‘Who is this kid?’ Come to find out, it was Tupac they were talking about.

“Every year, the school had a masquerade party called the Beaux-Arts Ball,” says Gerard. “Normally, people would perform and dress up in costumes. It was a tradition. This particular year, Darrin and I decided to perform as Run-DMC, so we had our black leather jackets on, fedoras, and shell-toes. After we did our Run-DMC performance, we heard there was going to be a battle in the hallway by the cafeteria, which had the best acoustics. One of the older kids, Zorian, and my friend Darrin started battling Tupac and another guy we didn’t know at the time. He was Tupac’s beatboxer and would eventually become the beatboxer for our group. That was the first time we met Dana, who we now call Mouse. His beatboxing had so much bass, and him and Tupac basically crushed everybody. Ironically, after that battle, we all became tight. Our mutual love for hip-hop bonded us together. And soon we started hanging out all the time and formed the group, Born Busy.”

Now rolling as a group, Pac, Dana, Darrin, and Gerard began to make plans to produce some demos. One fateful night, the guys were given the opportunity to go to a huge rap show that came to town—Salt-N-Pepa, Heavy D and the Boyz, Kid ’N Play, and go-go band E.U. In 1987, in Baltimore, that was the place to be. Historically, acts playing the Baltimore Arena would stay at the neighboring Days Inn. After the concert, the guys headed to the hotel where Tupac noticed Hurby “Luv Bug” Azor, who in passing first seemed interested to hear the group perform. But he suddenly changed his tune, and he snubbed Pac and Born Busy on his way in (possibly the biggest missed opportunity in the history of rap?). Still, the guys found a way into the hotel and onto the performers’ floor where they met a gregarious Heavy D, a megastar riding high off the successes of Living Large and Big Tyme. In only a matter of years, Gerard would produce songs that included the lyrical performances of Hev’s cousins Grap Luva and Pete Rock while Tupac’s rise to megastardom placed him at heights such as being included in Salt-N-Pepa’s “Whatta Man” music video [footage featuring Tupac’s face was edited out of the final video due to concern about his reputation at the time –Ed.].

By ’87, Gerard was regularly cranking out pause-button mixtapes for friends (with specially designed covers, of course). “I had my Casio keyboard, my SK-1, and then my SK-5, and the Mattel Synsonics Drums,” he says. “I also had an early Roland drum machine that I borrowed from my friend Darrin. Anything I could get my hands on, I would use to make beats. I figured out how to make my own multitracks with cassette-to-cassette overdubs. But what I noticed was, each time I recorded an overdub, the recording would speed up a bit. So by ear, I had to calculate how many overdubs would be needed for everything to be correct when I finished. When the tape sped up, the pitch went up, so I had to pitch down the instruments and slow down the tempo enough that, by the time I was done, everything would end up in the right key and tempo again. And once I perfected how to do that, the sky was the limit. That’s when I decided to record a bunch of songs to cassette—my first attempt at making an album.”

The tape in question was DJ Plain Terror’s Four-Four Beats and Spiritual Vibes. G remembers, “I recorded all these songs, I designed the cassette cover, everything! It was the first full package I compiled of my music and the cover design, combined. I gave it to a brother I met who eventually became a good friend, Neal Conway. Neal was working with Teddy Douglas of the Basement Boys as their keyboard player.” Douglas was taken by a track on the cassette, and decided to incorporate it into his next 12-inch. DJ Spen and Gerard re-created a more polished mix for the release, marking G’s debut on wax.

Geo arrived in Ed Koch’s New York City in 1988 as student at the esteemed School of Visual Arts, taking up residence in student housing at Sloane House on West Thirty-Fourth Street. At the time, it was the largest residential YMCA building in the nation, holding not only SVA students but Parsons School of Design and the New School students as well. “It was grimy over there. Not far from Times Square, Madison Square Garden, Penn Station, hustlers everywhere,” he recalls of the area now converted into high-priced, luxury apartments.

“My first year at SVA, I was frustrated because I wanted to go directly into my major, but they didn’t allow that. Everyone was required to do a foundation year, but I felt like I was going backwards coming from the high level of training I had at the Baltimore School for the Arts. My first day of painting class, I immediately knew I needed to switch to a different instructor. This guy wanted everyone to paint like Claude Monet, but I wanted to learn something different. And as I entered my sophomore year, that’s what fundamentally manifested.” A chance meeting with another SVA freshman, Matthew Reid (later known to the world as illustrator Matt Doo), would eventually set both of their lives on a major course of change. The NY native had a penchant for British comic book illustrator Simon Beasley on par with Geo’s love of the phantasmagorical album-cover master Mati Klarwein. Their fruitful yet short-lived collective Dooable Arts would make a long-lasting, if sparsely documented, impact on hip-hop branding, art direction, and album design. The two began sharing their work with each other, hanging out, asking each other’s opinions on art pieces, and constantly discussing the state of hip-hop.

Matt had long aspired to build his own art brand, but when he asked G to join forces, it opened significant new pathways for them both. What came after was the makings of a hip-hop design aesthetic rarely seen before or since, one that toed the lines of multiple forms of visual art: fantasy, street, fine, and graphic.

“When we were in school, most of the students in our classes tried getting typical jobs in design firms or advertising,” says Gerard, who signed his artwork as G-Young. “Matt and I, we had a different perspective on things—a different attitude. We’re hip-hop. We learned from our courses and classes, but we applied it in our own way. We had confidence in our way of doing things and trusted in our abilities. Plus, our street sensibilities combined with our professional training helped us secure opportunities that others weren’t getting. We put ourselves in a unique position that helped to raise our profiles globally.”

Dooable Arts would quickly rise from selling their T-shirts in Washington Square Park and at the Black Expo to landing the design work of many essential underground hip-hop releases of the era. While Organized Konfusion’s Stress: The Extinction Agenda may be the most lauded, you couldn’t pick up a rap magazine in the mid-’90s and not see Matt Doo and G-Young’s insignia somewhere. Bright comic colors splashed aside often nihilistic and narcissistic street scenes. It was cocksure and self-conscious at the same time, and even though their business card read “The Mentally ILLustrated Artwork,” there was a deeper commentary in each piece, whether the seismic apocalypse-themed cassette cover to Craig Mack’s promotional Teaser Tape or their racy Freaknik ’96 spot for TVT Records. Tragically, Matt Reid took his own life on December 11, 1998, an event that shook a community to its core and in its wake left Gerard (by now more commonly known as GE-OLOGY) profoundly heartbroken. “I wish he could have gotten the help he needed. It’s a sad, tragic story, because Matt was a brilliant—fucking brilliant—artist, and deeply loved. I cherish the history we made together and individually, and will forever be grateful for the brotherhood we once shared.”

The powerful surge of New York’s late-’90s independent hip-hop movement turned things into a full cottage industry atop the new millennium. Charged up with a crate full of collaborations, offering one impressive production after another, Geo’s list of contributions run the spectrum. Having made his own indelible mark painting and designing the seminal “Body Rock” (Mos Def/Q-Tip/Tash) cover back in ’98, he had long proven his proficiency in the dual disciplines, visual and musical, and his music began speaking volumes. A pair of gorgeous joints with elusive songstress Vinia Mojica, “Guilt Junkie” and Kombo’s “Sands of Time,” show an ear for quiet storm while back-to-back 12-inches for the Up Above label brought a soulful touch to the most traditional boom-bap. “Communicate,” featuring Talib Kweli and Brand Nubian’s Sadat X, swung with the early morning urgency of an A-train commuter while then-rising soloist Consequence’s “Babygirl” was accompanied by a masterful chop of T3’s rap from Slum Village’s “The Look of Love Pt 2.” Both record sleeves would also be illustrated and designed by G-Young for commercial release. Keen listeners will note his recurring use of interwoven vocal samples throughout tracks, in evidence with the Jigmastas’ “Reality Check” and Truth Enola’s “All Alone,” both prime mid-tempo masterpieces. Amid too many others to name, from De La Soul to Little Dragon, I’d be remiss not to mention standouts “B Boys Will B Boys” by Black Star and Mos Def’s “Brooklyn”—both perfectly capture the essence of the borough, the artists behind the mic, and the spirit of that time. It was through Mos Def’s 1997 Cutting Room Studios recording session that Geo would first meet Jay Dee (later known to the world as J Dilla). Several years later in the basement of Dilla’s home studio in Detroit, the two would find themselves sharing songs with one another. While Jay ran through iterations of what would be Welcome 2 Detroit, G played “Elevator Music,” a bossa nova big beat he made for the Unspoken Heard. It resonated deeply with Dilla and he inquired about beats for his upcoming major label debut on MCA. While the project never materialized, we do have the phenomenal GE-OLOGY remix to Platinum Pied Pipers’ “Act Like You Know” to imagine what Dilla and Geo could have really sounded like.

In recent years, the music has grown and matured in ways some would have never imagined could happen back in ’05 with the release of GE-OLOGY Plays GE-OLOGY. A decade later, his debut for Theo Parrish’s Sound Signature imprint exemplified a bold reintroduction to his ability to reinvent and challenge preconceived genre classifications. His reconstructed dance-tempo approach defies the constraints of traditional house music architecture in “Escape on the Lodge Freeway,” a marriage of modal piano over stuttering, fluttering hi-hats and kicks, a welcomed analog-driven contrast to the sleek synthetic status quo. The single’s monster A-side, “Moon Circuitry” is an intergalactic bubbler of four-on-the-floor footwork, with Mark de Clive-Lowe wailing on keys throughout—futuristic even for dance-music standards. His intricate, intimate relationship with the dance floor coupled with a collectable cache of vinyl gems makes it exceptionally clear why he is highly regarded as a DJ’s DJ, and a master storyteller through his poetic record programming. The lessons he’s learned across continents behind the decks are harnessed with care—sacred ingredients when cooking up timeless new magic with deliberate precision. GE-OLOGY is an inspired artist in any context.